Enter the Nightmarish World of Jim Shaw

A survey of the artist's expansive career in Antwerp invites audiences into a surreal realm populated by everything from Ken dolls to enormous golden chicks

A survey of the artist's expansive career in Antwerp invites audiences into a surreal realm populated by everything from Ken dolls to enormous golden chicks

Jim Shaw is a latter-day classical surrealist and symbol-wrangler on the frontiers of the American id, who seems to revel in the improbable arrangement of dream and pop images: Stevie Wonder, Wonder Bread, Yul Brynner, a Ken doll performing stand-up, a severed ear. In Mnemonic Device #2, Third Stone from The Sun (2020), which appears at the centre of his current solo exhibition, ‘The Ties That Bind’, highly detailed pictograms hover before the image of an enormous golden chick. A nudge from the painting’s title prompts us to decode each of the symbols (e.g., an image of a saxophone paired with a heroin needle = alto + H = ‘although’), a cipher that ultimately spells out lyrics from Jimi Hendrix’s apocalyptic jazz-rock reverie ‘Third Stone From The Sun’ (1967): ‘Although your world wonders me / with your majestic and superior cackling hen / your people I do not understand / so to you I shall put an end.’ The message provides little insight, itself a sort of admission of unintelligibility. For Shaw, words are merely the sinews binding his hallucinatory visions and the latent associations they might unravel for the viewer.

The sheer amount of art that Shaw has produced since graduating from California Institute of the Arts in the late 1970s presents a challenge for any mid-size museum survey. ‘The Ties That Bind’ wisely mitigates this problem by sampling only sporadically from Shaw’s denser narrative series, such as his comic-like ‘Dream Drawings’ (1992–2000) and more recent, large-scale acrylic paintings on repurposed mid-century theatre backdrops. Alternatively, curator Anne-Claire Schmitz opts for exhaustive stagings of two lesser-touted series, which together clarify the paranoid rationale at the heart of Shaw’s practice.

The first of these, ‘Study Drawings’ (2013–23) – a display of more than 150 pencil studies for paintings made over the last decade – appears at the exhibition entrance. Aside from showcasing Shaw’s technical mastery, the sketches, more than the finished paintings, elucidate a meticulous process of mimicry and mutation. Shaw hijacks the milquetoast, photorealist style of vintage advertisements or the zany expressionism of comics and cartoons, expanding and extrapolating them to construct sinister, Hieronymus Bosch-like hell visions: male underwear models melting into magma-like globs of peanut butter; household appliances converted into diabolical torture machines; grinning politicians (these remain relatively unaltered).

The second of the show’s more extensive series is Shaw’s staggering, glorious ‘Thrift Store Paintings’ (1974–present), a collection of artworks purchased from secondhand shops over the last half-century. The 500-plus paintings invent their own crude styles or crib from a line-up of familiar art-class references, such as Giorgio de Chirico, Salvador Dalí, René Magritte and Yves Tanguy, to immortalize family members, pets, celebrities and a legion of esoteric symbols of unknown importance. The works strain at the reins of proportion and linear perspective while Shaw laughs in the face of refinement. The unruly clashes of form and content – a postimpressionist baby, a cubo-futurist Humpty Dumpty, animals with sagging features and human-like limbs, pornographic portraits of America’s First Ladies – are as surprising, unprecedented and beautiful as the chance meeting on an operating table, proposed by 19th century poet Comte de Lautréamont, of an umbrella and a sewing machine. In the convulsive worlds of these anonymous artists, Shaw perhaps recognizes his faith in images and their mystical ability to contain our private beliefs and outlive us all in an afterlife of their own strange making.

For early surrealists a century ago, the paranoid encounters of dreams and coincidences once offered subversive potential: to crack the egg of reason and let the gooey yolk of the unconscious spill out into the world. Today, however, Shaw’s nightmarish visions feel more like anthropological records than pointed transgressions. Like Hendrix’s omniscient angel of death, Shaw observes it all in satellite-view, befuddled, amused and auguring doom.

Jim Shaw's ‘The Ties That Bind’ is on view at Museum of Contemporary Art, Antwerp, Belgium until 19 May

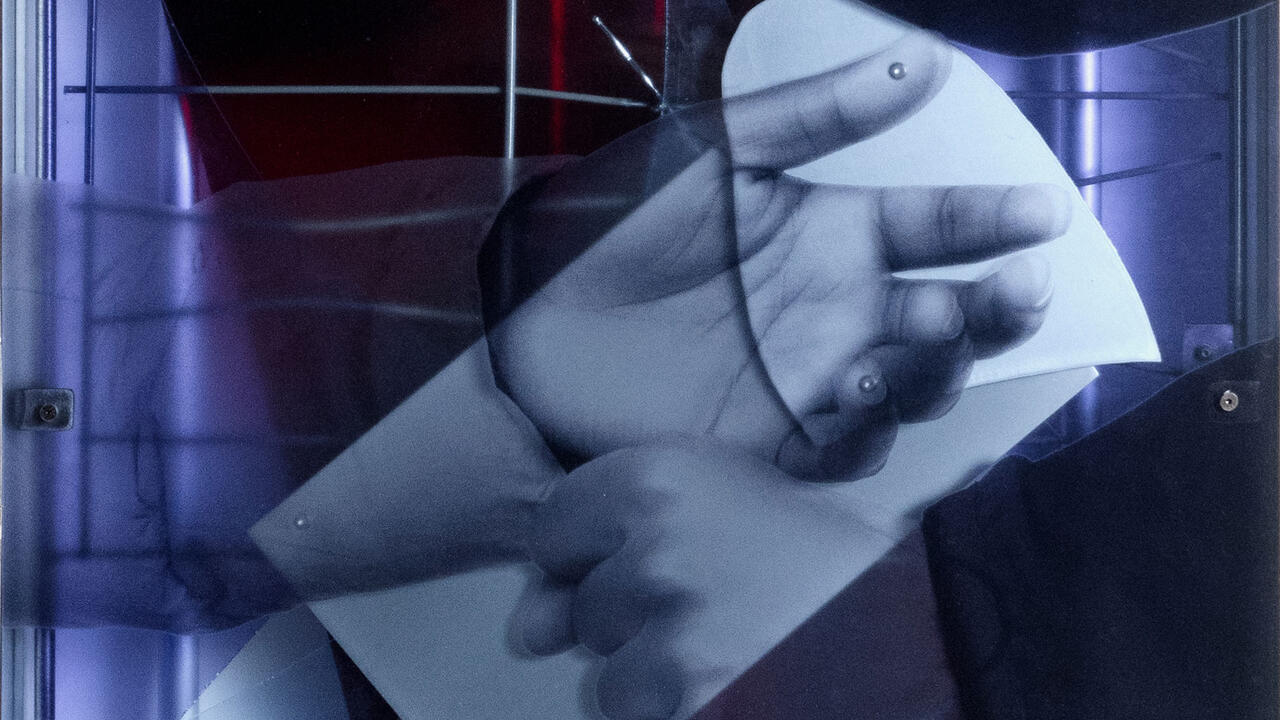

Main image: Jim Shaw, Octopus Vacuum, 2008. Courtesy: Praz-Delavallade Paris, Los Angeles