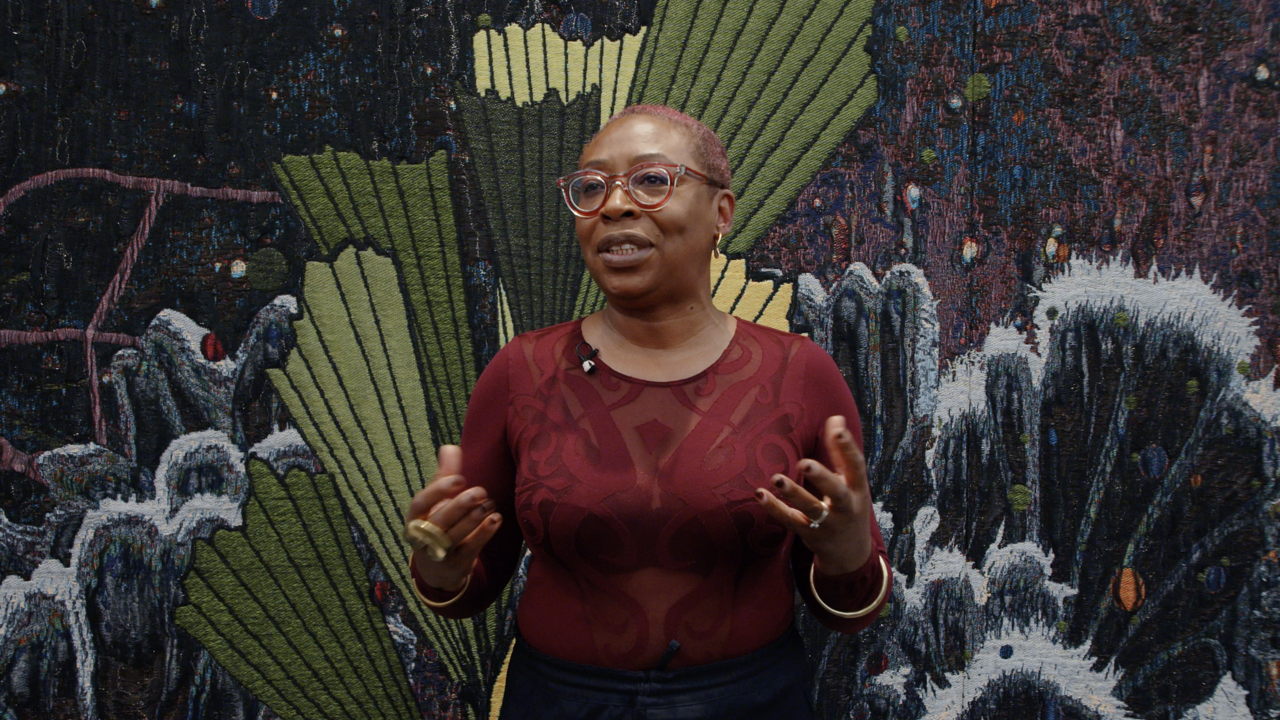

John Akomfrah

BFI Gallery, London, UK

BFI Gallery, London, UK

Mnemosyne (2010), a new single-screen installation by Akomfrah that premiered at the Public in West Bromwich earlier this year, again centres on the West Midlands and the experiences of postwar immigrants. Unlike in the 1980s, Britain’s diversity is now widely celebrated, to the extent that it has become a brand to be traded on. In Mnemosyne, however, Akomfrah interrogates the now-familiar images of our multicultural history with an evocative form of bricolage, for which he was given free rein of television, sound and film archives belonging to the BBC (who commissioned the project in partnership with Arts Council England; an extended version of the film, titled The Nine Muses, was shown recently at the London Film Festival).

The film is divided into nine sections, each named after one of the Greek muses (of which Mnemosyne, the muse of memory, is the first), which intersperse archive material – workers arriving from the Caribbean; Asian men pouring molten metal at a steel furnace – with shots of an unidentified frozen landscape. Mnemosyne opens with a hooded figure, face obscured, standing on the deck of a ship approaching a snow-covered coastline. Through newsreel footage, Britain is shown as a land of floods and blizzards, while a patrician English voice recites the opening lines of John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667) that talk of ‘man’s first disobedience’ and the ‘loss of Eden’. It’s playful – migrants from warmer climes have often described Britain as a cold and inhospitable land – yet elevates the subject matter to universal themes.

Over the course of its 45 minutes, pushed by the mood and rhythms of the soundtrack’s drone music, songs and industrial noise, the film takes on an increasingly mournful tone. A middle-aged black man lies listlessly among Birmingham’s ruined warehouse and factory buildings; a clip of the Conservative politician Enoch Powell’s anti-immigrant ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech (made in 1968) is replayed. This hints at the unresolved consequences of racism, but also at the disappearance of the jobs that originally brought migrants to Britain. Combined with the sense of environmental threat which pervades the film – not only through floods and blizzards, but the icy landscape comes from footage taken while Akomfrah was filming for another documentary, on the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill – it evokes a wider anxiety about post-industrial society.

Akomfrah takes this unease further still. Fleeting moments of warmth conveyed by footage of schoolchildren laughing, or teenagers dancing are undercut by a return to the icy land and the hooded figure. Here, the camera pans slowly, taking in strange vistas and frozen forests. On the soundtrack, words tumble from Beckett, Nietzsche, Shakespeare and Sophocles, often mere stumps of language that complement the warped landscape. An emotional climax is reached in footage of the American soprano Leontyne Price singing the spiritual ‘Sometimes I Feel like a Motherless Child’. In Mnemosyne this alienation is treated not just as a result of a specific history, but as a universal condition.

Powerful as the film is, there is a more prosaic sense of loss that British viewers might experience on watching it, too. Akomfrah began his career making equally unconventional films for mass television audiences; he benefited from a group of politically daring TV executives who sought to fuse popular culture with the avant-garde and ‘wrong-foot the public into illumination’, in the words of Michael Kustow, Channel 4’s first commissioning editor for arts. Among the many questions Mnemosyne raises, one is why such a grand project no longer seems possible in Britain today.