Josh Brand

Josh Brand has what he calls a habit of printing. As a teenager he had a darkroom in his basement, and he would experiment for long hours with the chemistry of photography; some years later he was hired as a professional printer. The New York-based artist’s commitment to the darkroom habitat is such that his works – which he thinks of as unique photographic ‘objects’ rather than as only images – are often the result of a completely camera-less procedure. Instead of life captured at a decisive moment, ‘Nature’, Brand’s second solo show at Herald St, presented what might be thought of as a negative of the real, a parallel dreamscape that is indebted to this environment of the darkroom.

‘Nature’ broke away from the constructivist aesthetic of his 2009 exhibition at the gallery, disclosing an interest in the animate world through photograms evocative of organic matter. These were shown alongside black and white snapshots of life outside the darkroom. On entering the space, viewers encountered six large untitled silver-gelatin prints that emanated a muddy light, which our eyes received only gradually, as if adjusting to a nocturnal landscape (all works 2011). These works are abstract, but at the same time they resemble an underwater landscape populated by microscopic cellular organisms. While we are not meant to know exactly how they were made, each print reveals a procedure of wet layering and in some the composition is traversed by drips of chemicals. Their beauty lies in the way technical control spills out into a more suspended psychic dimension. If Brand’s previous exhibition presented a fantasy of geometrical containment that paid tribute to the early Soviet avant-garde, this time he allowed chance to intervene more palpably in his photograms. The result is a heightened sense of uncertainty, a kind of mysteriousness epitomized by the haziness of the images.

Brand’s earlier works appeared to be constructed out of brightly coloured light, while in these images the printing paper is covered with thicker and darker stratifications. Interspersed throughout the exhibition were a number of c-type prints tinted with ink and dyes that from afar look like infernal landscapes. We need only glance at the two portraits in this sequence of images to get a sense of this: Visage is a painted black triangle with devilish red eyes that recalls a primitive mask, Figure a brutalized face drawn by scratching the colour off with a sharp point. What kind of nature is this? One that is, paradoxically, inhuman and somehow inorganic. Abstraction reaches a peak in this series, as rough brushstrokes and ink smears occlude any reference to living matter; synthetic chemicals take over water-bound organisms. Clearly, Brand’s sense of the ‘natural’ is indebted to the imagination – it feels inextricable from mental and manual manipulation.

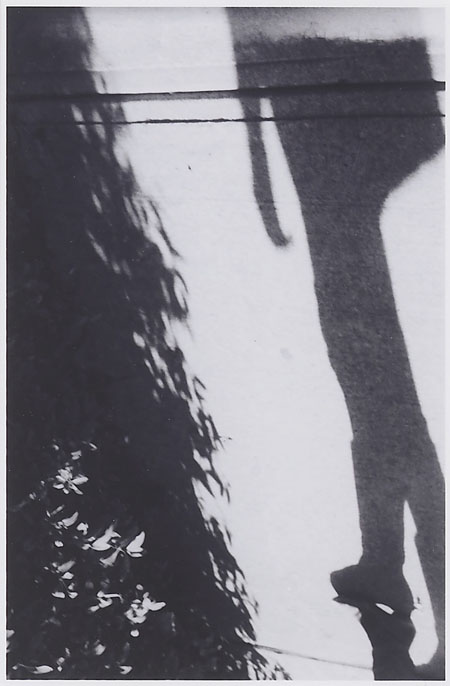

In the same spaces were hung a sequence of small black and white snapshots taken around Brooklyn – the first time he had exhibited recognizably representational photographs in the gallery. Cropped traces of Brand’s everyday life, these prints are exercises in precision and each is arresting in some way. They have a different luminosity to the rest of the works here, whiter and gentler; moving from one series to the other felt like witnessing the cycle of an eclipse. Switching rapidly between temperatures is part of Brand’s modus operandi. Although they portray life outside the darkroom, these works look more like fleeting apparitions made of light rays and shadows. Plants, dogs and people have a ghostly presence. Reality is halted in a state of inanimate suspension. A blurred close-up of a black dog’s face is entitled Ghost on Grand Street, but there are no spatial coordinates in this image with which we can orient ourselves. Like the whole exhibition, it is closer to the space of a dream.