How Julia May Jonas’s Campus Novel Navigates Bondage, Boomers and Calamity

Ian Bourland speaks to the writer about the persistence of university narratives and what it means to write novels in 2022

Ian Bourland speaks to the writer about the persistence of university narratives and what it means to write novels in 2022

Last month, playwright Julia May Jonas released her first novel, Vladimir, which tells the story of a middle-aged professor at a college in rural America who has to not only negotiate the snares of academia but also an embarrassing marital scandal when Vladimir, a striking younger colleague, enters her life – calamity (and bondage) ensues.

Ian Bourland: Tell me a bit more about the character Vladimir. He’s an academic approaching middle age who comes across as both self-assured and bewildered. Is he modelled on someone?

Julia May Jonas: He’s nobody that I know. He’s a little bit of a god, and I think I was letting myself fantasize about certain male writers that I have in my head, imagining how they might be. He’s also very clearly someone’s projection. Vladimir is a very 2021 character, in that he’s a man who really tries to please. That’s what makes him different and what becomes hard for him. He’s not unsympathetic, yet he also has an immense amount of ego, and both of those things exist at the same time.

IB: With a novel, you don’t have actors to animate him and other characters onstage – what effect did that have on your process?

JMJ: The pleasure of imagination and of writing a novel is being able to conjure that sense of the characters coming alive. During my day, I’d have one-and-a-half hours during which I could write. I found I couldn’t write for the theatre; it felt too depressing since theatre just wasn’t happening in 2020. I had a bunch of projects that were postponed and cancelled. These characters were like my friends, because I wasn’t hanging out with anybody else.

IB: What are some other ways in which shifting form changed your writing?

JMJ: The book started out like a play, as a monologue by the narrator that I ended up using. I knew I wanted her to kidnap Vladimir by the end. I felt like I couldn’t get there without being inside of her. I kept trying to get to that part and eventually I just realized that she was someone who I was just interested in – in the nuances of the way that she thought about things.

When you revise a play, you constantly check in with people. In my playwriting practice, I would bring ten to 20 pages to the group of actors I was working with and say ‘Let’s hear how it sounds.’ With this I didn’t let anyone read it until I was completely finished with a draft. You are working with the energy of the text; you can imbue it with a sense of rhythm in a different way than you can with a play. A novel gets to be the thing itself.

IB: While your protagonist is a middle-aged woman, she seems to be caught up in the power structures of both academia and of marriage, both of which come seem to converge in the character of her husband. He strikes me as this entitled male Boomer type – at once needy like a child and selfishly bound up by his own sexual desires.

JMJ: I think about him as kind of charismatic. I’m supposed to be repulsed by this type of person but if I saw them fall in the street, I would feel like devastated with sympathy. At the same time, they could make me feel worse about myself and anyone else if they criticized me in some way. It’s a type of man that affects you at a certain stage of your life – my father and teachers and all of these people that I really looked up to. That’s the trick with them, that there are oftentimes reasons to look up to them. Some of them could have acted better, though – certainly, some are morally correct and some absolutely transgressed.

IB: Given the circumstances she is navigating – a deceitful husband and a workplace scandal – the actions your narrator takes are both shocking and comically relatable. Do you see the book as a kind of catharsis fantasy for women who have to deal with the structural misogyny of the workplace?

JMJ: It’s this fear of ‘What if we did act on something?’ There’s always an aspect of ourselves that we trust or don’t trust. There’s that kernel that makes us wonder if at some point we could take that extra step, could step over a precipice. I’m always fascinated by that: how much trust we have in ourselves. Even writing about the kidnapping, I was like, ‘Is she going to do it?’ I didn’t know if she’d get there. When I got to the end, I was interested in that fiery, dream-like feeling. Every novel is a fairy tale, not real, even if it is attempting to be the realest of real, so I was interested in blurring fantasy and reality for her, and for us. What she has is an impulse to do something, and therefore keeps testing herself. As a writer, I wanted to ask, ‘What would it feel like if we did allow ourselves to do that thing we never thought we were capable of?’

IB: I did find it satisfying though, because men rarely get a comeuppance for their terrible behaviour.

JMJ: I don’t think there’s any ‘should’ about it – in general, people shouldn’t tie people up. But these kinds of characters can be instructive for us to consider ideas about taking what ours – or taking revenge. The book, if anything, is a testament to confusion. As women, maybe as people, we are often not connected to what we want – I certainly don’t feel like I’m connected to what I want or desire on a daily basis – and we’re so confused about it. So, I think what happens in the book is about a person’s flawed gesture towards accessing and acting upon desire.

IB: Why do you think the campus novel has been such a durable genre?

JMJ: Because the college campus is a microcosm of a human existence. Even if it’s a cliché, we can use it to explore aspects of our experience in an enclosed ecosystem. Even though I work in academia myself, I wanted to allow for the characters to exist in that ecosystem, rather than translate the drama to a different context, like the world of science. Books also interface with other books and many people who write books are working in universities. I gave myself permission to let it be that, to have an English professor as a protagonist, allowing the whole form to draw what it needed to draw that way. It was always such a pleasure to have books growing up that had a lot of references to other sources because I could then go forth and learn. I also tried to write something sensual that would have given me a lot of pleasure to read.

IB: Are you trying to address some of the issues around sexism in academia?

JMJ: Certainly there are patterns, especially in an older generation, where men will behave in certain ways that are completely egregious. There’s the socialization of saying, ‘Yes, I will volunteer for that curriculum committee, yes, of course’, but I now see that happening with both men and women. Maybe we can get to the point where it’s just about personality and not inherently structural. Being a university professor is a different job than it was for people who are now at the end of their careers – the way we interact with students, and they interact with us, and the way students view authority. Their comfort level with adults is certainly higher than when I went to college.

Of course, there were weird things that went on in my college – I went to theatre school. Teachers dating students, lots of intermingling of drugs and drinking and sex and all of those things. It was the water that I swam in, and so I think it might be impossible to get out of that water. For my narrator, as much as she is trying to be understanding, you can’t emerge from that fully. You can behave, but can you emerge from the experiences that you grew up with? I don’t know if it’s possible.

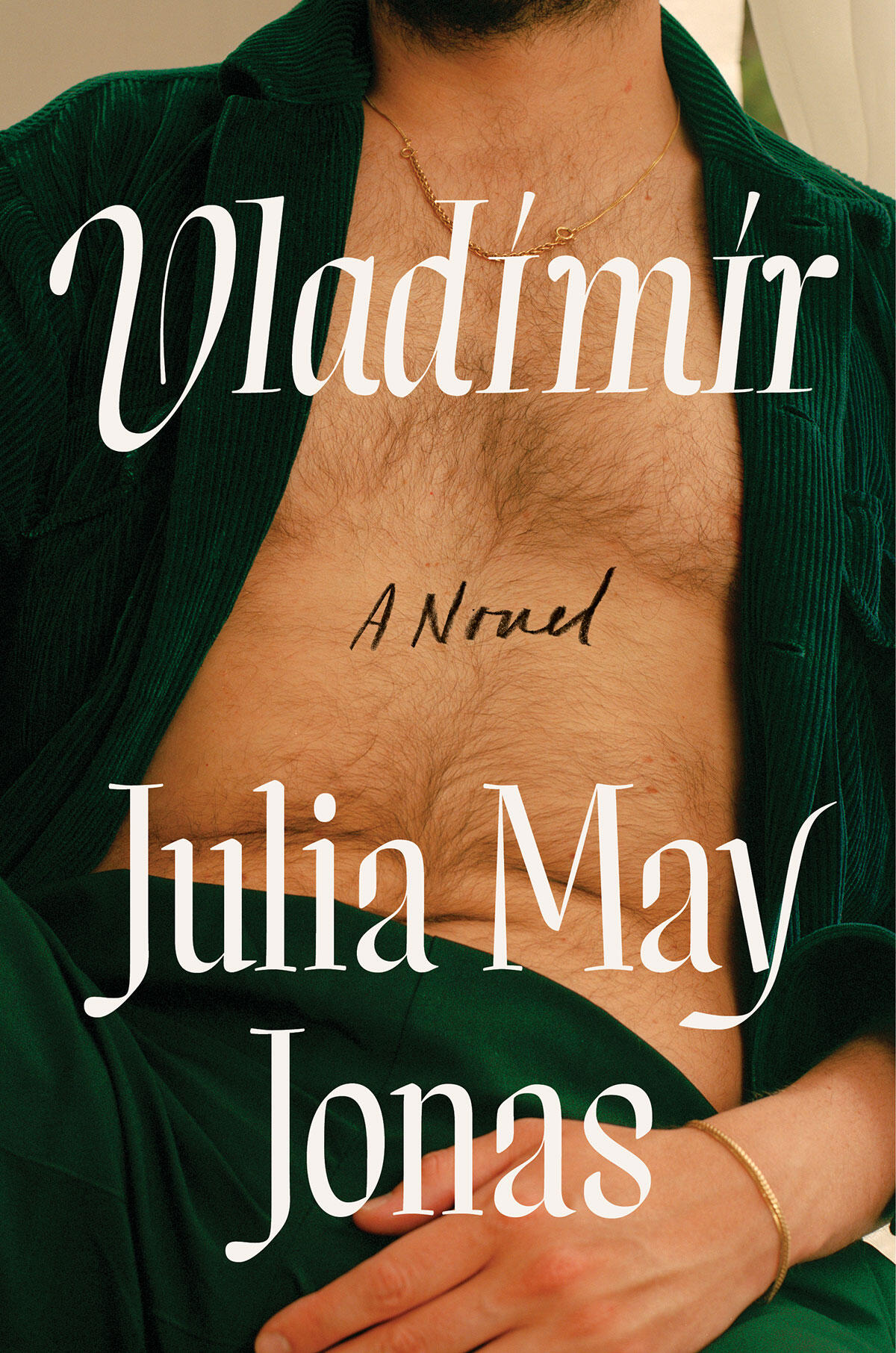

Main Image: Julia May Jonas, author photo. Courtesy: Avid Reader Press