Jutta Koether’s ‘Tour de Madame’: Red For Lipstick, Red For Blood

A retrospective at Munich’s Museum Brandhorst charts the artist’s career from the 1980s to the present, from ‘fem-trash’ figures to abstract forms

A retrospective at Munich’s Museum Brandhorst charts the artist’s career from the 1980s to the present, from ‘fem-trash’ figures to abstract forms

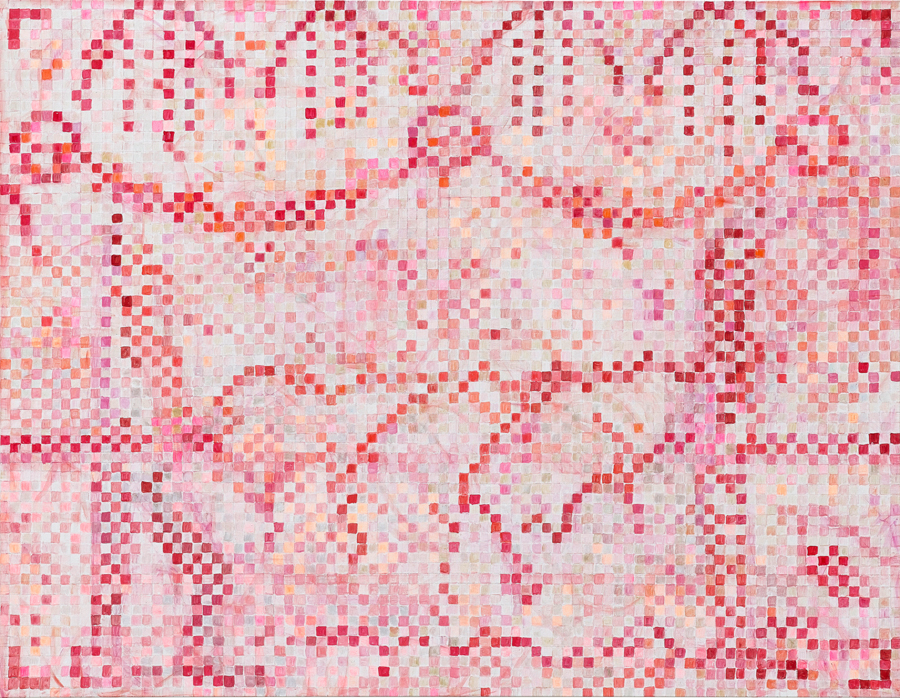

Presented over two storeys at Museum Brandhorst, Jutta Koether’s retrospective, ‘Tour de Madame’, is the first full overview of the New York-based artist’s work. The show draws an impressive arc, from her days in 1980s Cologne to works made after her 1991 move to the US. Koether’s early pictures, such as the small-format Straight Girl and Emma (both 1984), are part of the artist’s ‘cramped paintings’ (as the artist called them); crudely-painted, they contain distinctive figures once described as ‘fem-trash’ in Koether’s 1989 manifesto. Other, more diagrammic works, such as the ‘Hirtengesang’ (1985) series, feature closely-interlocked text and image. These are followed in the exhibition by Koether’s first pictures in red that became her signature style in the mid-1980s – containing a feminist charge, their red is said to allude, among other things, to lipstick and menstrual blood.

On view in the lower floor are later works, such as the 170 black acrylics of ‘Fresh Aufhebung’ (2004) – a series of quickly-painted abstract forms – and ‘The Seasons I-IV’ (2011), which references Nicolas Poussin’s ‘Four Seasons’ (1664) in red colour with transparent layering and stereotypical seasonal imagery. ‘Zodiac Nudes’ (2016) sees the artist return to her early ‘cramped’ style. The show culminates in the large central hall, filled by the artist’s most recent cycle ‘Tour de Madame’ (2018), which alludes to Michel de Montaigne and his wife’s famous towers. The twelve pictures are presented on a kind of glass screen whose angular footprint replicates the form of Cy Twombly’s ‘Lepanto’ cycle (2001) that is permanently installed on the museum’s top floor.

At this critical point, where the retrospective presentation gives way to newer works, the rigidity of the concept becomes apparent. Koether’s glass panels remain empty and formulaic, with no substantive link to either the surrounding architecture or to Twombly. The result is unimpactful. This is a shame, as Koether has previously used installations to stage painting as a discursive medium in richly referential and complex ways, as in her Hot Rod (after Poussin) (2009). An impression of this is given in the adjacent room that presents various documentary portfolios into a dense audio-visual experience: one of the most successful in the show. But, otherwise, the sometimes didactic presentation and the pat museification of the show tends to stiffen the artist’s fluid and genre-flaunting oeuvre.

The unsuccessful reference to Twombly also highlights a dilemma regarding interpretations of Koether’s work. Her pictures are replete with references to male painters and writers, such as Walter Benjamin, Marcel Broodthaers, Paul Cézanne, Gustave Courbet, Vincent van Gogh and Claude Manet. Some of her opulent nudes in particular, such as Golden Days (2014), brilliantly done in finely layered red paint on canvas, refer in their iconography and titles to artists such as Balthus or Courbet. Following the lead of Texte zur Kunst magazine, which has charted Koether’s work from the outset, this has been understood primarily as a feminist appropriation: a transformation and application of ‘female competence’ (as art historian Peter Gorsen wrote in the 1980s) to a male understanding of painting. But this argument is underpinned by a marked suspicion of painting as a genre which, if it is to be legitimized, must therefore be made legible as something else: as painting ‘beyond painting’, as a counter-canon or counter-history. In light of this exhibition, it is worth asking whether Koether is interested less in breaking with her male predecessors than deliberately inscribing herself within a specific historical lineage predicated upon an erotically desiring relationship with the object and the nude. A feminist approach that focussed less on differences than commonalities might offer more gender-related insights concerning the history of painting than endless, often purely rhetorical, knee-jerk reactions against it.

Translated by Nicholas Grindell

Jutta Koether: Tour de Madame is on view at Museum Brandhorst, Munich until 21 October.

Main image: Jutta Koether, Untitled, 1987, oil on canvas board, 18 × 24 cm, Courtesy: the artist and Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne/New York