Kind of Blue

How writers and filmmakers have responded to that most melancholy of colours

How writers and filmmakers have responded to that most melancholy of colours

The colour that grows like a thought, Out of a mood

Wallace Stevens, ‘The Man with the Blue Guitar’ (1937)

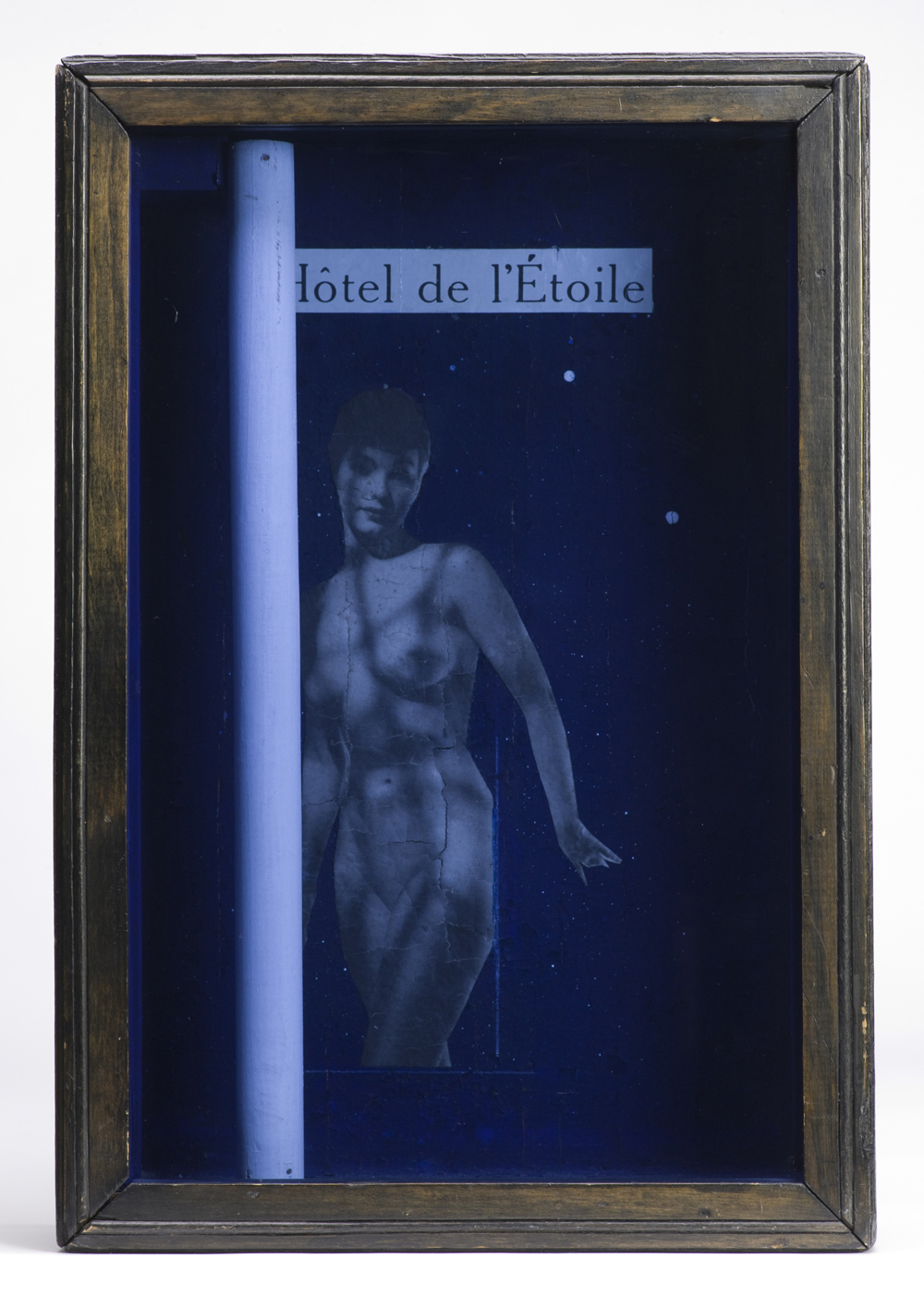

Strange, the things that emerge from the dark. There I was in bed, alone and feeling evil, blitzed. Midnight had come and gone without a sound. Nothing had occurred except for light rain and the slow conclusion of something gloomy for solo piano. I was unwell, my skull full of broken glass and snow, which is the ideal state in which to make notes on one of Joseph Cornell’s boxes. That was the night’s elusive task. Drowsy thoughts about his Hôtel de l’Étoile (c. 1958) scattered here and there: a dreamy starlet on a backdrop of night sky, nude, all tragic mien and eerie eroticism. Nothing materialized. Then out of the shadow and into the spotlight came something else: a phantom thought about a few books fascinated by the colour blue, and the odd aesthetic they all possess. A nocturnal, minor-key tristesse colours their tone, as if they’re hit by a blue-mood melancholia. Illumination over, I slipped into the shadows again and fell asleep.

The contents of these blue books are often the introverted, spooked expressions of a hypersensitive figure. The Beast in Jean Cocteau’s fairytale film, La Belle et La Bête (Beauty and the Beast, 1946) – that poor prince who was turned into a howling, lovesick mixture of tearful tiger and bloodied bear – would’ve written a splendid blue book. These are works too formally flummoxing to pin down, too private, too much like notes, odd fragmentary things. They don’t stay still for long, even though they’re the consequences of obsessive attention – how else would you distill Technicolor down to a solitary shade? Their writers don’t contemplate blue, immaculate, alone – though there are fine books about the mysteries of the colour, tout court. They gorge on all its symbolic meanings, then expel them in a tricky way, transformed, like so many smoke rings. They scarcely like to leave the house, turning inward to become ever-more solitary, and they transmit a chill in their pages, less the gooseflesh-tickling frequency of Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw (1898) and more an atmospheric frostiness: you can catch a cold from these books. The bodily dislocation that comes over you after a spell of deep reading is like the woozy dance of sleeplessness.

Here’s William H. Gass from his slender and melancholy book On Being Blue: A Philosophical Inquiry (1975) at the start of an associative drift through blue that begins things lusciously: ‘Blue pencils, blue noses, blue movies, laws, blue legs and stockings … the rotten rum or gin they call blue ruin and the devils of its delirium; Russian cats and oysters, a withheld or imprisoned breath … afflictions of the spirit-dumps, mopes, Mondays, all that’s dismal, low-down gloomy music, Nova Scotians, cyanosis, the colour of everything that’s empty, and so the increasing absentness of Heaven …’ Gass’s study (to be reissued by New York Review Books in April) remains an intoxicating example of essayistic invention and eccentricity. He swoons over blue and all the riches of its symbolic spectrum, from sorrow to sex. Blue’s suggestion of naughty eroticism is possibly forgotten now but Gass is especially enthralled by it. He thinks in a wounded way about his first flash of lust, caused by a stolen photograph of a naked, nervous girl under the blood-orange sun, and he often laments how impoverished erotic writing feels on the page. A Philosophical Inquiry, the book’s subtitle, is elegant, a sign of academic gravity, but what you sense when everything moves in this grand rapture is that Gass has abandoned critique and embarked instead on a sensual experiment. He uses words with narcotic pleasure, letting them swirl and fall slowly into prose. The book is a lush, ink-dark seduction conducted between the writer and his subject. You come untethered from the page and slip off into your own reverie. I think about the abyss from Max Ernst’s Approaching Puberty ... (The Pleiades) (1921) – Gass’s prose has the same sad glow – the deep and lonely Midnight (1986) painted by Helen Frankenthaler, and Winona Ryder’s character’s bedroom in the acidic, punkish comedy film Heathers (1988) where she writes down her teen angst like a scowling poète-maudite. (It’s tempting to imagine these blue books being composed in a sequence of similar rooms.)

This cascading of memory can turn into a mournful process. Carol Mavor’s book Black and Blue (2012) studies the work of Chris Marker, late Roland Barthes and Marguerite Duras in a sorrowful style that enfolds critique and memoir. At its centre is a huge hole: her mother’s memory (and so her mother’s memory of her) has slowly vanished. ‘How does one mourn someone who is still alive and yet who is not of this world?’, she asks at its outset, and the book is stricken by this tragic conundrum. Her prose is sumptuous and thick, scarcely thinking about argument and all its complications so much as tracing skeins of memory, echoes and metaphors across her life and art. Her sentences take labyrinthine walks, gliding in and out of other voices – a trick of quotation transforms Audrey Hepburn into Alice in Wonderland’s cat – in a kind of dreamy montage. She contemplates a photograph of the narrator of Marker’s Sans Soleil (Sunless, 1983). ‘Her face circled with the “O” of Once-Upon-A-Time, of Alice’s memory hole, of wishing wells, of film reels. She looks through a porthole of glass, transparently walled-off. Like Snow White in her glass coffin, she is near and unreachable, in two time zones at once …’ Like Gass, Mavor is allusive, light-footed, and takes a decadent pleasure in the slow unwinding of a thought. She’ll give you a lonely telegram in the middle of a page: ‘I am sitting in the bathtub counting all the bruises on my legs: a child in the body of a woman.’ The disconcerting sensation attached to this opulent, intimate writing is that you’ve climbed inside Mavor’s head, as if you’re taking a spacey wander through her memory before she lays it onto the page. Sometimes, the blue gets scumbled; a hazily evocative code word for a fantasy version of sadness, all claws removed, so what remains is a lukewarm, aesthetically inclined ache.

A sister volume, Blue Mythologies appeared last summer and found Mavor charming her familiar preoccupations into a lighter collection of blue notes. Often little more than a page is spent on each fleeting fascination, from the fathomlessness of International Klein Blue to the light in Krzysztof Kieslowski’s film Three Colors: Blue (1993).

Jean Rhys may be the grande dame of this blue fatigue, always drowsy, often lost, obliquely blue and discreetly damaged: ‘Well, here I am,’ she writes in Good Morning, Midnight (1939), ‘when you’ve been made very cold and very sane you’ve also been made very passive. (Why worry, why worry?) I can’t sleep. Rolling from side to side …’ A deadened ear would detect the unnerving notes to ‘very sane’, and something anxious, almost despairing, about the all-over fidgeting of these sentences. Rhys likes ‘blue air, easy to breathe’ but she’s always breathlessly moving, passing out and flickering back to life. Blue weaves through her work as anguish or, in brighter moments, as the gloom that descends when you can’t find a way out of your head on an eight-drink night.

And who haunts these books? Who else but everybody’s favourite ghost, Franz Kafka, a writer once defined in the 1922 Bestiary of Modern Literature – a bizarre little document in which Czech writers are described like animals in a hallucinatory zoo – as a ‘rare, magnificent moon-blue mouse’. The Blue Octavo Notebooks (1917–19), his elliptical half-diary, half-fiction compendia, are amongst his oddest works. Kafka’s writing, so marked by its painstaking choreography and peculiar breathing, is stripped down to its luminous bones: one-liners, notes on phantom illnesses and isolated tableaux. They contain some of his eeriest riddles – ‘a cage went in search of a bird’ – and his strangest sketches. ‘The crows maintain that a single crow could destroy the heavens. There is no doubt of that but it proves nothing against the heavens, for heaven only means: the impossibility of crows.’ (Blue books like to look at heaven in a frightened way.) Kafka usually sounds delirious from the chill air or else oddly becalmed, sitting alone with his spiritual ills at three in the morning while outside in the winter dark ‘the voices of the world become quieter and fewer’.

And this is the most vivid symptom of the blue book, the studied withdrawal from the world into the dark interiors of memory and imagination. That same spooky diminuendo occurs in each one, so all that remains is a haunted monologue. In blue books, writers map out their solitude and disappear into it. They do peculiar things to their prose, to give it precisely the sorrowful lushness of a bruise.