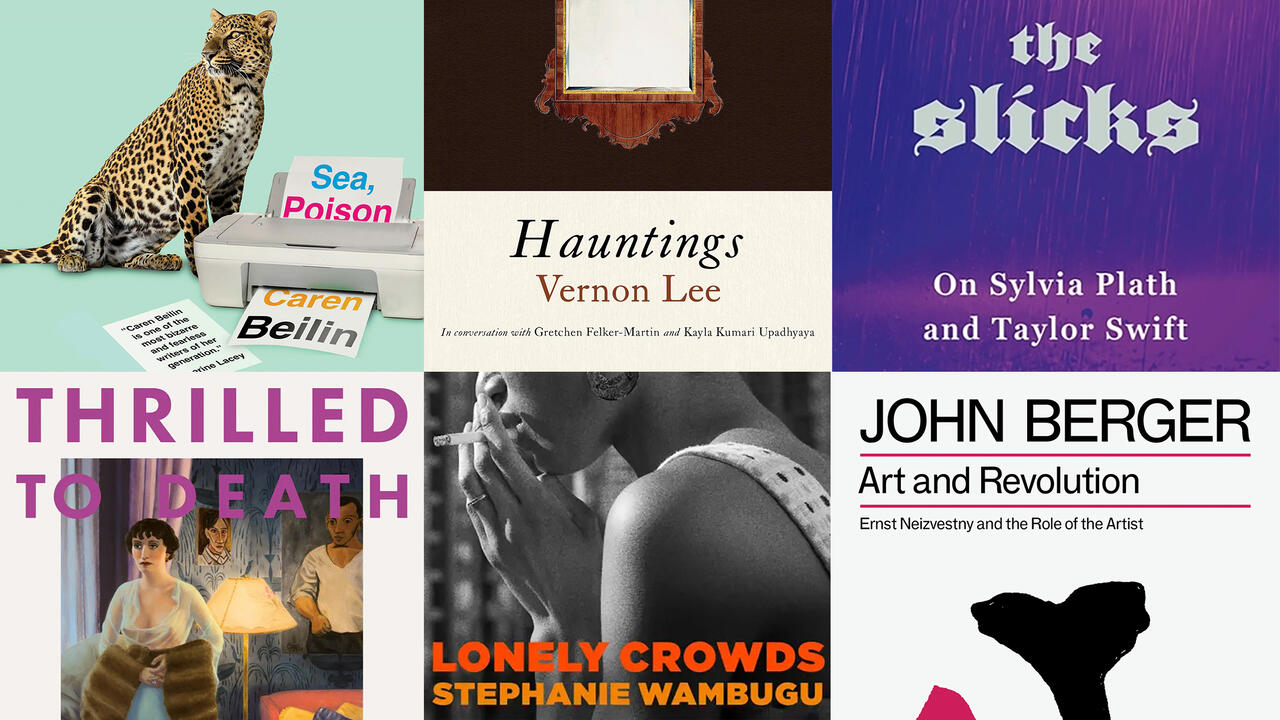

Large Issues from Small

Claire-Louise Bennett's meditations on still life and ‘the aesthetic value of the events, tasks and items that constitute daily life’

Claire-Louise Bennett's meditations on still life and ‘the aesthetic value of the events, tasks and items that constitute daily life’

To write something of any importance probably requires the onset of at least one good idea and it is seldom that an idea, good or bad, occurs to me – I just have thoughts, lots and lots of passing thoughts, few of which are particularly worth investing in. On the rare occasions I’ve forced myself to triangulate these reflections so that they begin to harness the combative verve of an idea, I have been reminded of the late cultural anthropologist Clifford Geertz, who observed in The Interpretation of Cultures (1973) that ‘man is an animal suspended in webs of significance he himself has spun’. Fairly recently, I discovered that the French poet Francis Ponge also had something of an aversion to academic spin. ‘No doubt I am not very intelligent; ideas are not my strong point,’ he tells us, in his superb essayjournal, My Creative Method (1948). Ponge’s resistance to ideas has nothing to do with his degree of intelligence; the difficulty arises from opinions and philosophies themselves, which, he goes on to explain, ‘have always seemed to me utterly fragile, caused a certain revulsion, a sense of the emptiness at the heart of things’. An emptiness, yes! I enjoy ideas inasmuch as I enjoy arguing the toss from time to time; if I take them too seriously I find that, rather than helping me to grasp the world, they induce the peculiar sensation that it is falling away, like water, between my suddenly insensible fingers. Ponge goes on to make a further admission: he says that ideas disappoint him because he agrees with them too willingly, and here I find myself in accordance with him again – I, too, believe pretty much anything I’m told. Being impressionable where opinions are concerned is not particularly advantageous. But perhaps this susceptibility is just an expression of a broader sensitivity, so that, in another context, one is not so much gullible as receptive: willing and able to intertwine with the world and all its phenomena – including its most unremarkable sundries.

This is certainly true of Ponge. His percipient enthusiasm for ubiquitous items and small creatures is exacting and intimate: these things are not merely separate entities, but the very conditions of his own existence. ‘Their presence, their obvious solidity, their thickness, their three dimensions, their palpability, indubitability […] all that is my sole reason to exist, my pretext, so to speak; and the variety of things is in reality what makes me what I am.’ Throughout 45 years of writing, Ponge produced dozens of prose poems that configure, with remarkable originality, the essence of simple things, such as a candle, a crate, moss, an eiderdown, olives, a dish of fried fish, mistletoe. The list goes on – seldom does a human being make an appearance. On the rare occasions one is brought into the frame, the mysterious relationship between the human psyche and the material world is skilfully invoked with exquisite palpability. In Les Plaisirs de la porte (The Delights of the Door, 1942), for example, Ponge writes: ‘Kings don’t touch doors / They do not know this bliss: to push one of those large familiar / panels gently or brusquely ahead of oneself, to turn and put it back / in its place – to hold a door in one’s arms.’ The stuff of Ponge’s world is not regarded at arm’s length: it is opened, closed, held. The linking of the personal with the planetary, in what Ponge called his ‘description-definitions-literary-artworks’, brings to mind Gaston Bachelard’s conception of the home, which he so beautifully set out in The Poetics of Space (1957). This intensely fertile meditation on domestic space discloses the interior life of our immediate surroundings, recasting the home as ‘an embodiment of dreams’ where the assembly of tables, chairs, caskets, drawers and wardrobes encompasses profound cosmic potential. Like his fellow Frenchman, Bachelard was alert to the flush bliss of opening doors: ‘If we give objects the friendship they should have, we do not open a wardrobe without a slight start. Beneath its russet wood, a wardrobe is a very white almond. To open it, is to experience an event of whiteness.’

When I was very young, I made drifting lists that were triggered by the things on my bedroom floor, migrated outside to name those things that I imagined inhabited the dark – wolves, moths, fireflies, greying tennis balls tucked beneath black conifers – before turning inwards to tentatively alight upon that strange menagerie of internal phantoms that has been skimming across my marrow since day one. Writing was – and is still, to some degree – a way of linking the inner, the outer and the beyond along the same imaginative continuum. As Bachelard put it: ‘Large issues from small.’ Yet, despite the vibrant poetics that his meditation upon familiar space brings forth, the home and its accoutrements are still routinely thought of in predominantly domestic terms, amounting to nothing more than an environment characterized by habit, drudgery, tameness and unvarying outcomes. Seen from that dour angle, it’s hardly a strata of life that seems worth reporting on. In recent years, visual and performance-art practices have done a great deal to foreground the aesthetic value of the events, tasks and items that constitute daily life. Challenging the hegemony of fine art and its emphasis on beauty, religion and greatness, everyday aesthetics alert us to those myriad responses, from disgust to consummation, that calibrate our day-to-day environments and the activities they are host to. While this is a crucial and exciting turn, I feel that some of the artworks that have emerged from this discourse often present an estranged pastiche of ‘everyday life’, and reinforce generic ideas of the domestic. Too much of the human role is apparent in them, perhaps. I’ve sometimes wondered if it’s people who subdue things, rather than the other way around. Liberated from their customary function, objects regain a marvellous ambivalence which hints at their belonging to a limitless system far more generative than the one they are assigned to through their routine encounters with individuals. An unoccupied stage set has often seemed to me to transmit a greater dramatic charge than the play that comes to pass upon it. Perhaps it is for similar reasons that some of the artworks I like best are still-lifes from the Renaissance period.

The absence of human subject matter in still life meant that, as a genre, it wasn’t held in as high regard as portraiture, landscape or history painting; in my view, it is the very eschewing of a blatantly anthropocentric theme that makes these canvases so singular. And the more stripped down the compositions the better. Among my favourites is a still life, or bodegón, by the Spanish painter Juan Sánchez Cotán. He completed Quince, Cabbage, Melon and Cucumber around 1602, at a time when most artists were exclusively occupied with depicting religious tableaux, battle scenes, royal figures and so on. Here, in this arrestingly austere arrangement, a quince hangs from a thin string at the top-left corner of an apparently paneless window; its outstretched leaves make it look winged and restless, as if at any moment it might take flight and disappear upwards out of the frame. Suspended beneath it is a cabbage, whose downcast aspect brings to mind Cyrano de Bergerac’s defence of vegetable life in his novel A Voyage to the Moon (1657): ‘To massacre a man is not so great a sin as to cut and kill a cabbage, because one day the man will rise again, but the cabbage has no other life to hope for.’ Below, on the unmarked sill, a cleaved melon has come to rest. The seeded surface of its hacked interior is the only area in the painting that is free from shadow; yet, here, unadulterated light seems indecent, intrusive, exposing the disarrayed pips and the dent of the severing blade to disquieting effect. Beside the melon is a slice of itself, one end in the merciful umbra of its bigger portion, the other end rent from its stippled skin. A year or so after he completed the painting, Sánchez Cotán joined a Carthusian monastery, part of a Catholic order whose emphasis on contemplation meant that the monks passed their days in silence and solitude. Perhaps only a painter with the capacity for hermetic spiritual dedication would feel moved to wrench these humble comestibles away from the raucous chaos of a muggy kitchen and present them in isolation. As De Bergerac, writing less than 50 years later, said: ‘Plants, in exclusion of mankind, possess perfect philosophy.

Another Spanish painter who created still lifes that transcend the daily round is Francisco de Zurbarán. It is not surprising to discover that the artist was very much influenced by Sánchez Cotán. As in Sánchez Cotán’s windowsill, the table of his Still Life with Lemons, Oranges and a Rose (1633) is placid and unmarked: there are no traces of human tasks, no nicks in the wood, no stains from previous repasts and neither of the table’s two ends can be seen. There is a similar precise ordering of objects and, like his predecessor, Zurbarán conjures mesmerizing black backdrops that pull our attention through the tangible elements onto an amorphous metaphysical plane. A metal dish of four citrons stands in front of this darkness, the fruit nosing the static air like deracinated moles. On the right is a saucer, upon which a cup of water stands askew, watched by a pale rose poised on the rim. Between both is a basket piled with coy oranges and a sprig of spiky blossom. The light on this arrangement seems to be coming from behind my left shoulder, picking out the protuberant lemons, some of the huddled oranges and one side of the obstinate cup, where it stops. The light does not, or cannot, penetrate the darkness behind; we could be anywhere. I do not consider what hand gathered and organized this produce, nor what mouth will consume it; again, these fruits are not for eating. This is not a slice of life.

Not all still lifes produced in the 17th century were as temperate as those made by the Spanish masters. The lavish feasts displayed in German artist Georg Flegel’s brimming paintings reflect values that are the antithesis of those embedded in the frugal bodegón. Here food, glorious food, is definitely meant to be gorged on, guzzled and gobbled: its supreme abundance attests to great wealth, enormous appetite, boundless pleasure. The hallucinatory excess is stomach churning. Flegel’s visual inventory of the quaffing habits of the merchant and noble classes offers up a dizzying glut of hazelnuts, shellfish, apples, lobsters, herrings, waffles, small birds, roasted chestnuts, dates and cherries, fried eggs – and, as if this wasn’t enough – mice, stag beetles, parrots, dragonflies and ladybirds, which flit and fidget around the enticing feasts, fixing their beady eyes upon the heaped and glazed delicacies. (Not all of this happens in the same painting, I should add!) Even an illustration of relatively simple fare, such as Still Life with Bread and Sweets (1637), manages to be indulgent and garish, with its spindly gossamer insects eerily pawing at encrusted, pearlescent pastries.

I want also to mention an Italian painting, though I have nothing to say about it. In his book Still Life with a Bridle (1991), the Polish poet and essayist Zbigniew Herbert recognizes ‘the agonies and vain effort’ of trying to translate images into words: ‘Literary description’, he says, ‘resembles the laborious moving of heavy furniture.’ Where Giovanni Ambrogio Figino’s Metal Plate with Peaches and Vine Leaves is concerned, it would resemble moving heavy furniture around a house I have broken into. Dated between 1591 and 1594, it is an early example of a Renaissance still-life painting. If one were to fall in love with a man because of how he spends his time, one would have to wonder if there is a man more worthy of adoration than a 16th century artist who passed his days painting a plate of peaches, which, having just come into ripeness, are protected by the gentle reach of fading vine leaves. If there is a story here, and surely there is, it is better to leave it unspoken.

When I am feeling a little like Geertz’s suspended animal, I return to concrete practices in art and in life. When the world feels convoluted and scribbled over, as lost amid infinite formulations as a face between two mirrors, shopping for fruit and vegetables, taking them home and unpacking them, arranging them in various dishes and bowls and, later, chopping them in a silent kitchen upon a cold, stone board, imbues my cells with a bit more density. These things are grounding, you might say. Yes and no. As this chopping goes on, a peculiar thing happens: my hand is no longer my hand, this knife is no longer my knife and this aubergine is no longer this aubergine but all the aubergines that ever were. Perhaps it’s these sorts of experiences that prompted Thomas Mann to wonder in his novel Joseph and his Brothers (1943): ‘Is man’s “self” narrowly limited and sealed tight within his fleshly ephemeral boundaries? Don’t many of his constituent elements come from the universe outside and previous to him?’ It is certainly an idea that resonates most strongly with me while I stand in the kitchen and, through the sudden generalizing of my personal reality, begin to experience a generalizing of myself, so that I am but an instance of woman, and my heart is but an instance of the overlapping heart that has always strobed the night sky with its fantastic schemes, and has always burrowed its plangent suffering deep into the earth’s marrow. It is at such moments, when the inner, the outer and the beyond are caused by simple things to somehow merge, that one briefly feels at home.

Main image: Jacob van Hulsdonck, A Still Life of a Laid Table, with Plates of Meat and Fish and a Basket of Fruit and Vegetables (detail), undated, oil on panel, 72 × 104 cm. Courtesy: Johnny Van Haeften, London