Laws of Motion

Guilt, humour and dislocation in Andy Holden's cartoon universe

Guilt, humour and dislocation in Andy Holden's cartoon universe

Without doubt, one of the most startling and talked-about works at Glasgow International last year was Andy Holden’s two-channel, 55-minute video Laws of Motion in a Cartoon Landscape (II) (2016). A dazzling journey through the history of animation, critical theory, physics and art, before arriving at modern politics and Trump Tower, it catapulted the artist into what he describes as a genuinely cartoon universe, in which the phone never seems to stop ringing. He has taken the film around the world – from New York to Hong Kong and Ukraine – moving from his isolated and ramshackle studio in the flatlands around the British town of Bedford to a capacious – though equally ramshackle – city-centre space.

The irony of this transformation is not lost on Holden. Since 2011, he has been presenting Laws of Motion in a Cartoon Universe as a multimedia performance, delivering a running commentary as he splices and plays film clips. Since finally biting the bullet and including himself in the cartoon footage – as an animated bespectacled avatar – the artist now simply screens the film without further intervention. ‘But’, he told me, ‘as I became a cartoon, the world I came to inhabit became a cartoon, too.’

Laws of Motion began as an attempt to formalize the laws of cartoons, first outlined in Mark O’Donnell’s 1980 article on the topic published in Esquire magazine. When Bugs Bunny keeps running even after traversing the edge of a cliff, he only falls when he becomes aware of the abyss beneath him. So, Law 1: ‘Any body suspended in space will remain in space until made aware of its situation.’ When the rabbit smashes through a wall leaving a rabbit-shaped hole, we reach Law 2: ‘Any body passing through solid matter will leave a perforation conforming to its perimeter.’ Yet, as Holden developed his version of these ten ‘non-Newtonian’ Laws, the strange logic of cartoons seemed to have a far wider purchase.

When we met to discuss his film last year, US President Donald Trump had just tweeted that Meryl Streep – who had delivered an anti-Trump speech during the Golden Globe Awards the night before – was one of the most overrated actresses in Hollywood. Unlike the usual, measured sanguinity of a statesman, Trump’s relentless tit-for-tat is pure Tom and Jerry. Law 10: ‘For every vengeance there is an equal and opposite revengeance’. In cartoons, there are no third parties to arbitrate disputes: each character just bashes the other, and with a speed exactly equal to that of today’s social media.

For Holden, the stars of this world are a president and a popstar. Just as Trump can do politics and tweet about Arnold Schwarzenegger’s low ratings on The Apprentice, so, too, can Kanye West move from family man to outspoken bad guy in seconds. ‘These are figures who walk out over the cliff every day,’ says Holden, ‘masters of fluid reinvention’, and it is no accident that he has used footage of the two of them meeting in Trump Tower for his new animation, What a Time to Be Alive (2017).

For Holden, the golden age of animation – which ran from the advent of sound cartoons in the 1920s to the late 1950s, and whose principal figures include Tex Avery, Max Fleischer and Chuck Jones – was a premonition of things to come. Technology now allows information and data to move with cartoon swiftness. We segue from one thread to another at lightning speed, with no time to reflect and find meaning. Slogans and ‘facts’ explode and then evanesce in an instant. This is today’s political world for Holden: a cartoon landscape that requires not just its own cartography but its own navigational aids. Knowing its laws is not enough: we need to know how to inhabit it.

Habitation has always been central to Holden’s work. Parallel to the Laws of Motion performances, since 2012 the artist has run a series of ‘Lectures on Nesting’ with his father – the well-known ornithologist Peter Holden – who speaks with fluency and precision about the nesting habits of birds. For his father, the construction of nests is an evolutionary given, an instrument in the service of survival. For the artist, a nest is an object resulting from a series of decisions and choices. As the audience views slides of these extraordinary constructions, the conflict between two anthropologies becomes acute. Son interrupts father, counterexample contests example, and it becomes clear that what is at stake are two entirely different ways of viewing the world: one based on teleology and necessity, the other on chance and free will. Academic combat is played out here as Oedipal drama – or is it the other way round?

It was, after all, a scolding from his father that led Holden to produce, years later, a number of sculptures and paintings. Visiting the Great Pyramid of Cheops as a child, Holden purloined a tiny fragment of rock from the side of the monument. His father admonished him in Kantian fashion: ‘If everyone who came here took a piece of rock, there would be no pyramid left.’ Plagued by guilt, Holden not only made a work documenting his return of the rock some 15 years later, but produced a knitted and foam model of the fragment that is 10,000 times the size of the original. Titled Pyramid Piece (2009), this vast object, which was shown at Tate Britain in 2010, is proportional not to the size of the original stone but to the size of the artist’s guilt. It was followed, in 2011, by The Cookham Erratics: a group of six large knitted rocks displayed at the Benaki Museum in Athens that contained hidden speakers relating the story of their own appurtenance. While the exhibition was a witty response to Britain’s appropriation of artefacts from Greece, it was also an admission of guilt: the sculptures were replicas of rocks that had been stolen from Cookham churchyard in the UK, where a group of youths – including Holden’s great-uncle – had pelted the artist Stanley Spencer as he painted his Resurrection (1924–27).

Yet, the transgressive act at Cheops could never be fully undone. The little rock, Holden says, came to embody all his sins and indexed what he describes as his own out-of-placeness in the world. Elaborating rather than negating this, the artist then created vast half-boulders out of wood sheeting (‘Follies’, 2006–14). Like massive urban nests, he placed them, without explanation, on a beach, a field and halfway up the side of a building. Found paintings of rural scenes would also suddenly sprout these intrusions, as Holden added boulders painted in the style of the original artist. The rock was now everywhere.

Part of the verve and agility of Holden’s work lies in his seemingly effortless movement across media. Wool, steel, wood, paint, plaster and sound are all used to create incongruities – structures that shouldn’t be there but are, nonetheless. Heavy, blobby sculptures constructed from multicoloured plaster macaroons have been a constant presence in the artist’s work since 2008 and sit uncomfortably in the gallery space like some bulbous primal matter. Inspired by stalagmites, they rise up from the ground, slow and cumbersome. But if their out-of-placeness is legitimized by the gallery context, Holden can also be found in the street outside selling ‘fakes’ of his own work, which are made from the very same materials and by the very same process as the pieces in the exhibition.

And this is exactly Holden’s guide to life in the cartoon landscape: to be inside and outside the picture at the same time. Just as the artist can stand in front of a gallery selling cheap replicas – or, rather, originals – of his work, so the only way to survive a world in which nothing seems stable is to find ways of simultaneously operating within it and outside it. His vast installation Maximum Irony! Maximum Sincerity 1999–2003 – first shown at the Zabludowicz Collection in 2013 and adapted for Spike Island, Bristol, the following year – explores this same duality. For the work, which comprises film, sculpture and performance, the artist cast teenagers from Bedford as himself and his friends, meticulously restaging their youthful manifesto, M!MS. This was their call for irony and sincerity in art and life or, as the manifesto puts it: ‘the willingness to be lied to and the will to believe! It’s about the intense sadness of our unrealistic dreams, and the intense joy of our desire for them.’ In a video, we hear Holden arguing with actors attempting to re-create this failed project. The autobiographical moment is assembled and disassembled, with Holden once again both inside and outside the story of his own life.

Holden’s two-person show with Steve Roggenbuck at Rowing, London, in late 2016, ‘WHEN U INSTAGRAM MY DEAD BODY, USE WALDEN BUT TAG IT #NOFILTER’, presented this strategy crisply. Catharsis (2016) comprises a display table covered with Holden’s late grandmother’s collection of porcelain cats and a video of the artist opening their packing cases and commenting on each piece. The film belongs to the genre of unboxing videos that are so ubiquitous today: people describing in real time how they feel as they open, say, their new iPhone that has just arrived in the post. In an entirely unscripted monologue, Holden digresses on cats in Egyptian art, in dreams and in literature, until he reaches the uncomfortable topic of his grandmother’s death.

As the artist enthusiastically shares his serial reflections on cats with the speed and swerve of the cartoon landscape, we feel the muteness of the ceramics themselves. Incarnating what Holden calls ‘thingly time’ – the time of making, of duration and of all that has been thought about an object – the porcelain takes us away from the kinetic logic of cartoons. Where the cartoon landscape flattens time, objects and artworks bring it back.

A comparable split haunts the birth of modern science itself. If cartoons transport us to a world that rejects the physics of Isaac Newton, his contemporaries asked how a body in space could know its distance from other bodies. Classical physics was perplexing for many because of such questions, as it seemed that the sentient body had disappeared. Newton himself believed in the perpetual action of a divine body in every single part of space and time. Yet, as the mathematics of Newtonian science became more dominant, so these quandaries about the presence of the body were lost. Holden’s project is to bring back this sentient body, showing us how ‘we are always in two different spaces at the same time’, with two different modes of temporality. Living there can’t be easy.

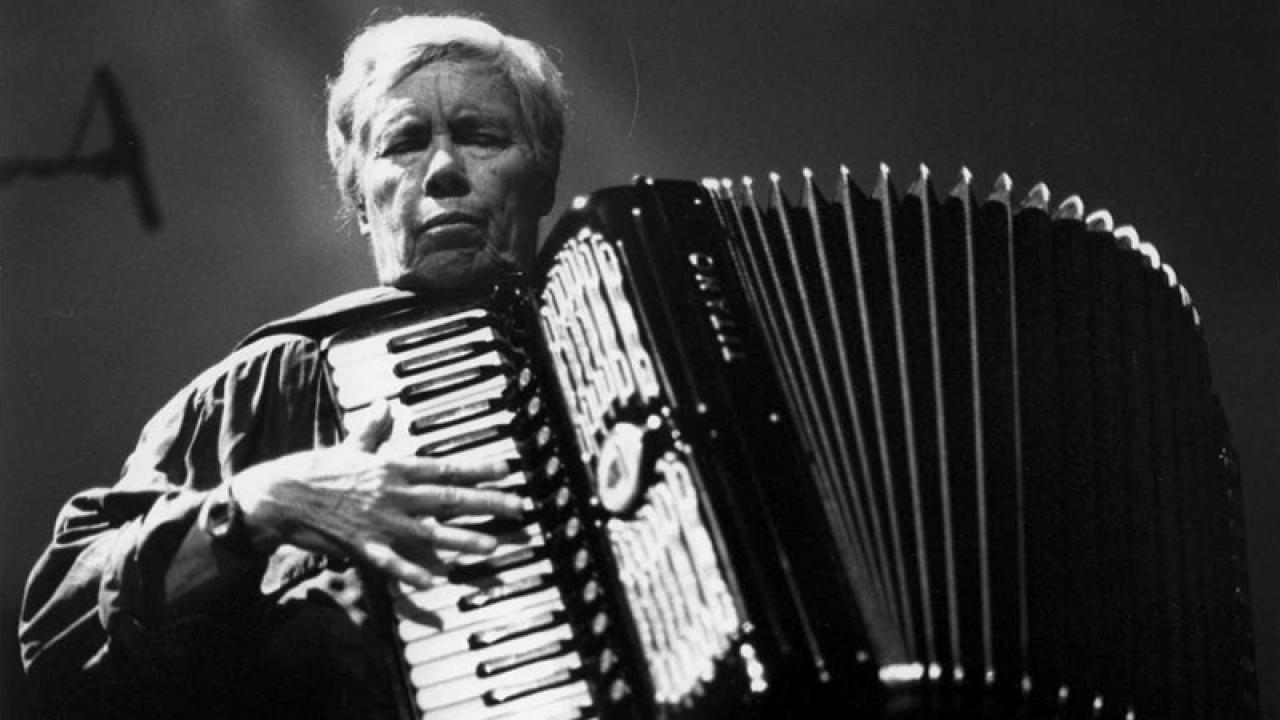

Main image: Andy Holden, What a Time to Be Alive, 2017, video still. Courtesy: the artist