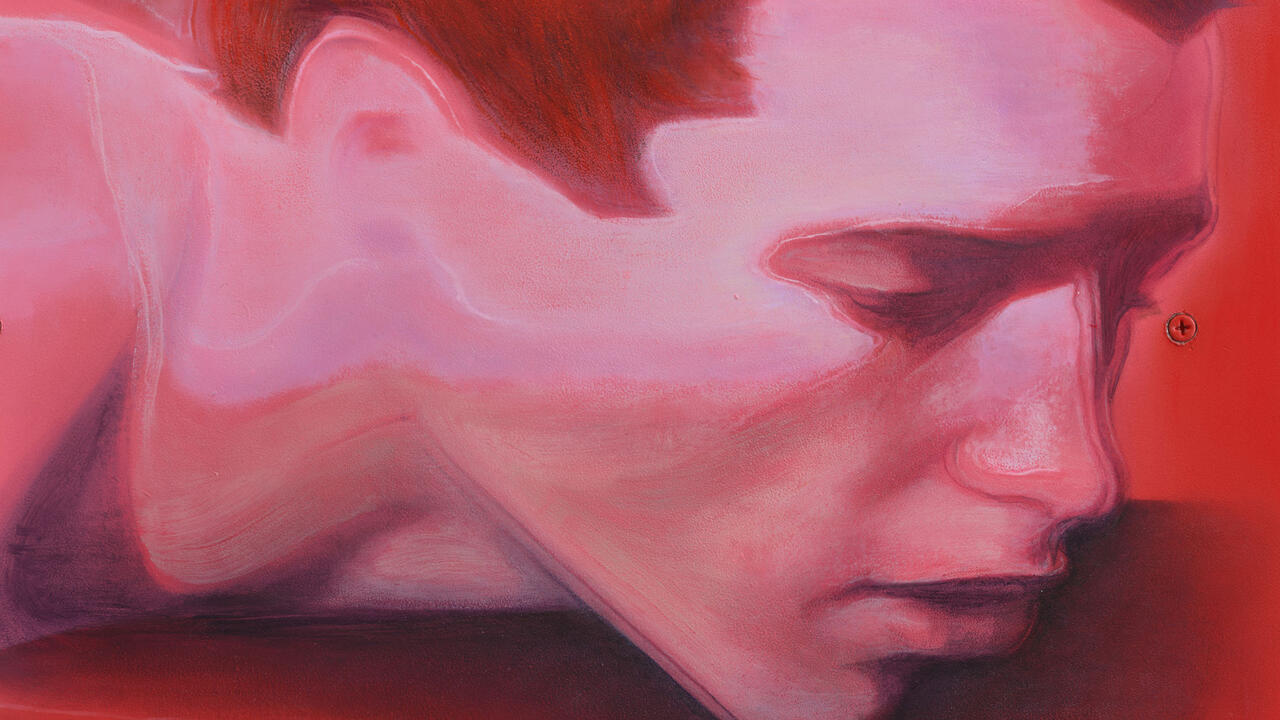

‘Learning How to Be Queer Again’: Remembering Douglas Crimp (1944–2019)

The late art historian and activist inspired generations of young artists and writers to better teach themselves

The late art historian and activist inspired generations of young artists and writers to better teach themselves

Less than a dozen pages into Douglas Crimp’s coming-of-age memoir Before Pictures (2016), the art historian recounts the split he experienced when he moved to New York in 1967 after graduating from Tulane University. In New Orleans he had discovered himself on Decatur Street in the French Quarter where sailors, sex workers and queers shared a riverfront and could find one another to get what they needed. In Manhattan, an island whose stratifications separated the zones for art and sexuality into seemingly-impenetrable rooms, Douglas struggled at first to map his coordinates and find a way to blur the city’s limits; he had to learn how ‘to be queer all over again.’

I wouldn’t meet Douglas until the end of the 2000s – when he invited me over to his downtown apartment for a smoothie before work – but in that first conversation, he seemed equally ready to learn how to be queer again. And in the following decade, during which we became friends and collaborated, during which he supported me and became a teacher, he remained curious, earnestly asking about artists whose work was new to him and keenly listening as I thought on my feet on walks across Lower Manhattan or post-performance subway rides.

The Douglas I knew – and I imagine the Douglases I didn’t know, too – believed that our worlds could begin again. He also had the conviction to learn anew and an ability to make younger friends who might teach him how. Perhaps most famously (and most traumatically) he did just that when he left the haute modern art journal October in 1990 after thirteen years as its editor, finding ACT UP through then 26-year-old Gregg Bordowitz. Reflecting on the divorce almost two decades later, Douglas told fellow activist Sarah Schulman: ‘I came to realize that…how the art world was responding to AIDS…was not sufficient.’ In his deceptively straightforward account, Douglas reminds us that sometimes you have to leave your art job to figure out how to be queer again.

Disappointment, ambivalence, uncertainty: Douglas gave shape and provided a history for these mixed feelings. In the 1980s, he and the late Craig Owens – Crimp’s graduate school friend and fellow balletomane – had explored the knowledge held in these torqued emotions. Care with rage; mourning with militancy. Against the normalizing force of political flattening, he told us, fluids unlicensed by expediency seep out of our bodies and express shared feelings. In Douglas’s writing, this often took the form of first-person narration drawn from family experiences: his grandmother corrects his reading of a Degas photograph, causing Douglas to recognize that its meaning is ultimately produced by subjectivity; his father’s memorial service triggers the blockage and subsequent puncture of his tear duct, prompting a visceral recognition of his unconscious. Again and again, the family and the self are transfer points for engaged criticism, a rhetorical tactic he learned from feminist reworkings of psychoanalytic theory.

At the end of ’80s, Douglas refused art history’s social limits and created room for new fields of inquiry: queer and film theory, visual and dance studies. In his hands, these were not new disciplines to be codified and protected, but unruly thought practices aimed at making good on the promise that had beckoned him to look and write and look again: that art can be a necessary part of everyday life.

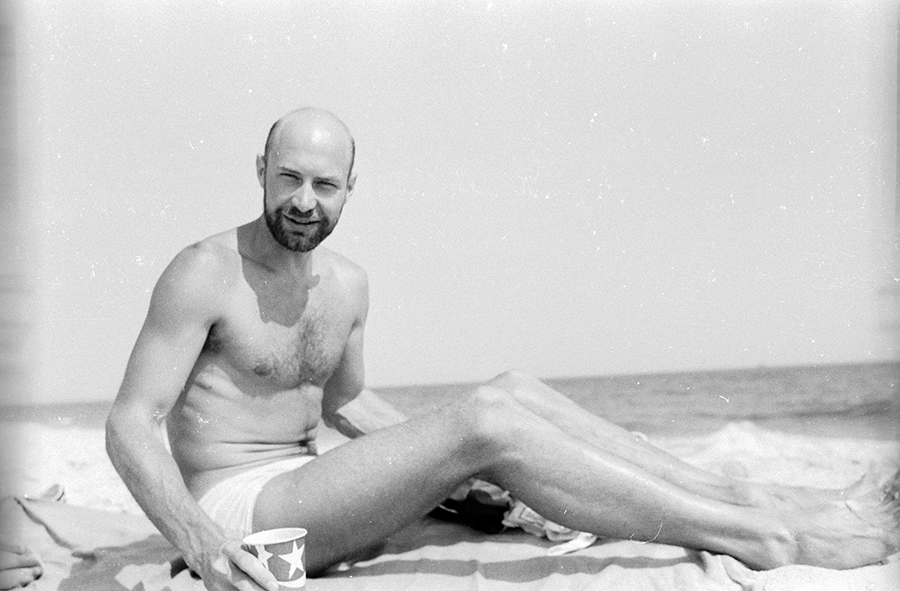

In his memoir, shortly after he arrives in a New York, Douglas describes being queer as ‘a matter of a world you inhabit, not something you simply are.’ Queerness is social. It doesn’t describe the behaviour or identity of an individual, but rather an atmospheric pressure like the weather, or a natural element like water, fluid and penetrable. Douglas often theorized about queer watery places: the Hudson River piers where men sunbathed and cruised for sex, as photographed by Alvin Baltrop, or Water Island, where he once invited Ellsworth Kelly for shrimping and a fling.

Inhabiting Douglas’s queer world involves a commitment to a sexual politics and an intellectual project fuelled by desire and chance contact. The act of searching that occupied him – for answers, for connections – is cruise-y, unfinished business. It is skeptical about the machinery of institutions and open to changing course and going underground when necessary. Douglas practiced this kind of inquiry throughout his career with the activists he met at ACT UP; with students at the University of Rochester and the Whitney Independent Studies Program, where he taught for many years; with curators who followed his influential exhibitions ‘Pictures’ (1977) and ‘Mixed Use, Manhattan’ (2010), co-curated by Lynne Cooke; and, of course, with the artists whom he loved and who loved him.

When I read Douglas’s work for the first time as an undergraduate, queer theorists such as Lee Edelman were staking their bets against futurity, arguing against the marshalling of the figure of the child as a symbol of an oppressive status quo. We children were skeptical. In Douglas’s dissertation, which became his first book On the Museum’s Ruins (1993), we found an alternative argument. In the book’s titular essay, he argues that because of photography’s reproducibility and the external information required to secure its meaning (a caption, for example), its appearance in the museum had caused the object of art, its history and its reason for being to flow beyond the walls of the institution. Artists’ turn to photography was at once the symptom and elixir of the museum in crisis. Although Douglas wrote this essay before his ostensibly queer work, I found a through-line to our post-AIDS moment: just as photography had heralded the end of the autonomous, secluded museum, and just as the ‘Pictures’ artists had advanced an alternative view of art’s history and necessity in a time of disrepair, so too could the spectre of AIDS create another model for the germination of queer ideas, outside the strictures of heterosexuality. Queer children can find their future in a tomb, where the historical lessons of loss have been stored. Mourning, protest and dancing are intergenerational forms of knowledge transmission interred there; they are how we learn and relearn to be queer. This is what Douglas’s work made possible for me, and it is this future work we must continue as we mourn his loss.

Main image: Douglas Crimp. Courtesy: Douglas Crimp, 2016; photographer unknown