Let’s Get Together

‘Painting Forever!’ opens across four Berlin institutions

‘Painting Forever!’ opens across four Berlin institutions

This September, four of Berlin’s public institutions – the Neue Nationalgalerie, Kunst-Werke, the Berlinische Galerie and the newly established Deutsche Bank KunstHalle – will launch a joint exhibition, ‘Painting Forever!’. Does this signal a new era of cross-institutional collaboration: a pooling of ideas, funding and public space in order to achieve a common goal while circumventing the ongoing financial crisis in the public art sector?

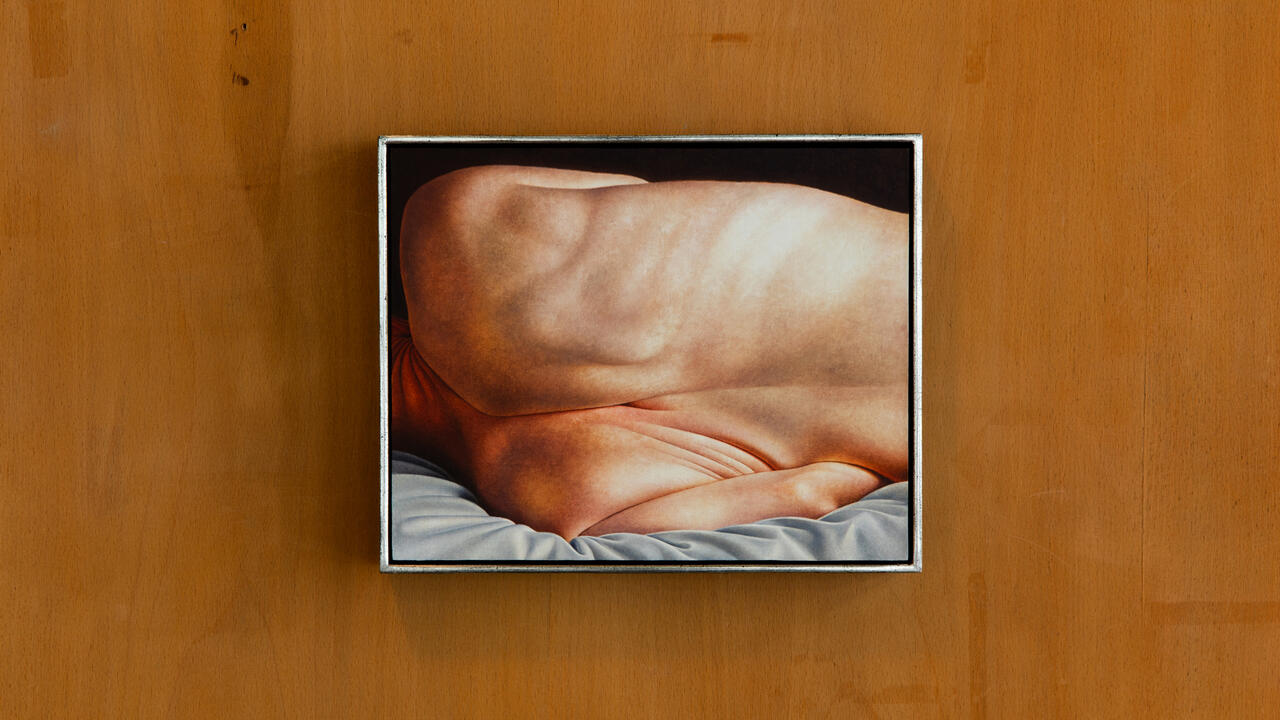

Co-operation is a ‘craft’, writes sociologist Richard Sennett in his 2012 book Together. ‘It requires of people the skill of understanding and responding to one another in order to act together,’ but it is ‘a thorny process, full of difficulty and ambiguity and often leading to destructive consequences.’ Given that each of the four institutions involved in ‘Painting Forever!’ has a distinct agenda and identity, this collaborative venture may seem somewhat surprising. In fact, this initiative came from the Berlin Senate and the Mayor’s office. A funding offer tied to the concept of a joint endeavour, its focus was to be on artists working in Berlin (a follow-up to the contentious, state-funded 2011 exhibition, ‘Based in Berlin’). While the theme of painting was chosen by the first three participating institutions (the Deutsche Bank KunstHalle which, until a few months ago, was the Deutsche Guggenheim, came on board later), the four exhibitions that will open during Berlin’s ‘Art Week’ in mid-September suggest not so much the thorny process of working together, as business as usual. Kunst-Werke will present a fast-paced survey of around 70 artists who live (or lived) in the city; the Berlinische Galerie will show a large-scale exhibition of Franz Ackermann’s work; and the most prestigious venue, the Neue Nationalgalerie, will showcase four painters – Martin Eder, Michael Kunze, Anselm Reyle and Thomas Scheibitz. This surfeit of mid-career male artists will come as no surprise to followers of the Neue Nationalgalerie, where there has been only one solo show by a women artist (Taryn Simon) since Udo Kittelmann was appointed director in 2008. In light of this astoundingly unreconstructed approach, it is hard not to see guest-curator Eva Scharrer’s four-woman show at the Deutsche-Bank KunstHalle (featuring works by Jeanne Mammen dating from the 1950s to the ’70s, alongside contemporary works by Antje Majewski, Katrin Plavčak and Giovanna Sarti) as an attempted antidote.

How, I wonder, would the results of a more ambitious and, in Sennett’s terms, ‘difficult and ambiguous’ collaboration look? What kind of ‘destructive consequences’ could it court? Here is one fictitious scenario: fill the Neue Nationalgalerie’s hallowed halls with women painters; ghettoize the successful mid-career males at the Berlinische Galerie; and divert some of Deutsche Bank’s financial resources from its own private KunstHalle to the notoriously underfunded Kunst-Werke – which since the 1990s has been the city’s most vibrant international and experimental platform for art.

Kunst-Werke’s exhibition, titled ‘Keilrahmen’ (Stretcher Frame), takes an overview of the medium, showing one painting per artist, salon-style, in the gallery’s central hall, in order both to elucidate the exhibition’s precept – by providing a literal overview of the diversity of artistic practice in one medium – and to display its intrinsic limitations. Such questioning of curatorial and institutional framework is a quality that Ellen Blumenstein, Kunst-Werke’s new chief curator, has been emphasizing since the start of her tenure in early 2013. In April, she initiated ‘Relaunch’, a three-month programme that stripped the gallery space of art work and exhibited the institution itself ‘naked’, thereby highlighting its present under-funded state, while also launching a frenetic series of twice-weekly events. ‘Berlin is a discursive city,’ says Blumenstein. ‘Since the 1990s, it has a strong tradition of questioning artistic production.’

Like Blumenstein, the new Head of Visual Arts and Film at Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW), Anselm Franke, cut his curatorial teeth at Kunst-Werke in the early 2000s. This summer’s highly successful ‘The Whole Earth: California and the Disappearance of the Outside’, as well as Franke’s earlier touring exhibition ‘Animism’ (2010–12), have brought a ‘speculative historiographical’ form of exhibition – to use the curator’s own terminology – to this inter-disciplinary institution.

‘After Year Zero’, which will open at HKW in September, is another such essayistic show. Subtitled ‘Geographies of Collaboration’, it deals explicitly with co-operation in political and historical terms, and was developed through a series of workshops that began in 2012 and involved filmmakers John Akomfrah and Jihan El-Tahri as well as curator Olivier Marboeuf, along with Franke and co-curator Annett Busch. The exhibition gives equal billing to several concurrent events, including discussions, film screenings and what Franke calls a ‘curated conference’. He aims, so he told me, to ‘create convergences that are off the register of normal contemporary art curating’.

Perhaps, given Berlin’s ‘tradition of questioning’, it is just such a creation of discursive convergences that is most strikingly absent from the ‘Painting Forever!’ collaboration. In fact, it was originally proposed that the conference organized by Isabelle Graw at Harvard University in April 2013, ‘Painting Beyond Itself: The Medium in the Post-Medium Condition’, should be reincarnated in Berlin to accompany the four exhibitions; inadequate funding meant this idea was sadly shelved. However, since the Berlin Senate apparently intends ‘Painting Forever!’ to be the first in a series of similar collaborative projects, it seems there will be future occasions in which the city’s institutions can hone their skills in the art of co-operation.