Life in Film: Ane Hjort Guttu

The Norwegian filmmaker on childhood heroines, docu-fiction and Swedish love stories

The Norwegian filmmaker on childhood heroines, docu-fiction and Swedish love stories

The first film I remember seeing was Pippi Långstrump (Pippi Longstocking, 1969), directed by Olle Hellbom; the soundtrack was by the famous jazz pianist Jan Johansson and Inger Nilsson starred in the lead role. She had a great acting style; it was very straightforward. Every Scandinavian child has seen this film. Astrid Lindgren wrote the first book in the series, Pippi Långstrump, 70 years ago, and there hasn’t been a female protagonist in a children’s book since who can beat her. The scene that had a real impact on me was the one in which two policemen try to catch Pippi to take her to an orphanage but she ends up playing with them on the roof of her home.

I also vividly remember the series of Italian animations La Linea (The Line, 1971–86), which were created by the cartoonist Osvaldo Cavandoli. These short films follow a man created from one line who walks around encountering things. Suddenly, the draughtsman’s hand – like God’s – would come into the cartoon, erasing or fixing things. When La Linea came on – it was called Streken in Norwegian – my younger brother would run around the house screaming ‘Streken, Streken!’ That kind of hunger for cartoons and popular culture created by a single state TV station is hard to imagine today.

The first film that made a great impression on me as a grown-up (and as a future artist) was Wim Wenders’s Der Himmel über Berlin (Wings of Desire, 1987), which I saw when I was 16. I only remember certain scenes, the strongest one being that of an old man walking through the wastelands of Potsdamer Platz; before reunification, it was an enormous no-man’s land split in two by the Berlin Wall. The angels in the film can read people’s thoughts and we hear the old man recalling that, when he was young, Potsdamer Platz was ‘the busiest intersection in Europe’. Der Himmel über Berlin references many symbols of the 19th century, such as the railway station, the library and the circus. This might have been the last time in film history that these tropes were used without them seeming sentimental. Perhaps they were already kind of kitsch then but, as a 16 year-old, I didn’t realize it.

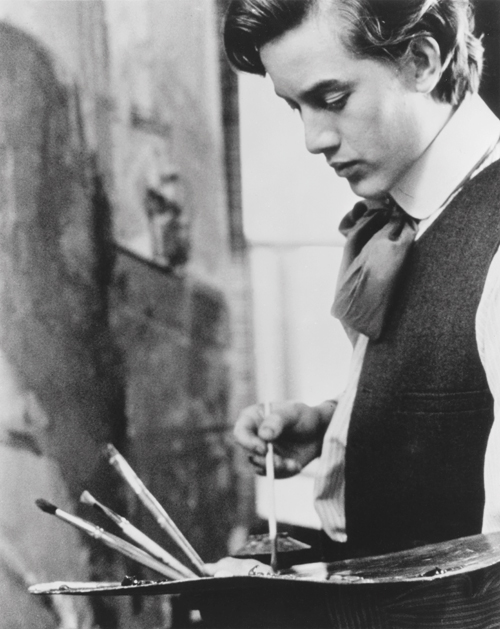

Peter Watkins’s films have been a big influence on my work, particularly Edvard Munch (1974) and La Commune (Paris, 1871) (2000). Watkins made Edvard Munch in Norway with the great but little-known cinematographer Odd-Geir Sæther. In several of his films, Watkins makes use of the documentary-style interview, which functions as a break between the more fictional scenes. While Munch (played by Geir Westby) remains remote, Watkins ‘interviews’ many of his contemporaries, such as the painter Oda Krohg (played by Eli Ryg) and the writer Hans Jæger (Kare Stormark). They talk matter-of-factly about social problems and questions around gender, creating a strange mix of the Scandinavia of the 1890s and the 1970s.

Edvard Munch is also one of the few films that conveys the artistic process in a convincing way: the sincerity with which Watkins explains Munch’s motivations for painting his various versions of ‘The Sick Child’ (1885–1926) was a great inspiration for my own film, Time Passes (2015).

In La Commune (Paris, 1871), Watkins employs a similar docu-fiction-style interview and combines it with a theatrical stage set. The film is almost six hours long: much of it comprises political discussions and statements. The filmmaker’s method – a research process that involves the cast and crew – is productive and inspiring. During the filming of La Commune, Watkins cast a large number of amateurs and left much of the research and scripting to them; some of them later formed working groups and seminars on the Paris commune and its historical legacy.

In my earlier films, like This Place Is Every Place (2014) or Freedom Requires Free People (2011), I was greatly influenced by Swedish filmmakers Jan Troell and Roy Andersson. Their work expresses a strong view on late social democracy and the decline of the welfare state in a melancholic and poetic visual language. In Troell’s film Sagolandet (Land of Dreams, 1988) there is an unforgettable scene in which a man fights huge angelica plants with all the means available, from poison to machete. I guess it symbolizes the alienated human being in a technocratic state, and his need for control; yet, at the same time, it’s very funny. In Andersson’s En kärlekshistoria (A Swedish Love Story, 1970) I remember a scene where the drunk adults rave, screaming in the forest in the morning light. They have been up all night, partying and quarreling. Then the protagonists – a very young couple – emerge from the morning mist. The contrast between the hopeless, bitter adults and the innocence of youth is almost too painful to watch. En kärlekshistoria is one of the most romantic films ever made, anywhere.

I mostly remember scenes, not characters or an entire film. To me, it seems as if many films are created in order to build up to, and support, these amazing scenes that just grow and grow in your mind. For example, Claire Denis’s Beau Travail (Good Work, 1999) crescendos in the final dancing scene, which is crucial to the meaning of the rest of the film.

Recently, I have seen and enjoyed Citizenfour (2014), Laura Poitras’s film about Edward Snowden: a study of a highly principled person – his psychology and political insights. I find Poitras’s stance an important one: her filmmaking is activism in a very concrete and productive form.