Luc Tuymans

White Cube, London, UK

White Cube, London, UK

Few birds have such a mixed fan base as pigeons. At the beginning of the French Revolution they were killed in their thousands as symbols of privilege, while in England pigeon-fanciers have come to represent all that is grim and sad up North. Many things to many people, in London they elicit reactions that swing between a Mary Poppins 'feed the birds' sentimentality, and disgust inspired by their reputation as 'flying rats'. Entitled 'The Rumour', Luc Tuymans' most recent show in London spins off from a vortex of cryptic connections, the central motif of which is this most enigmatic of birds. Two paintings of pigeons were interspersed with six other images, including depictions of birds' eyeballs, a man's face, an underpant-clad bottom and a cage.

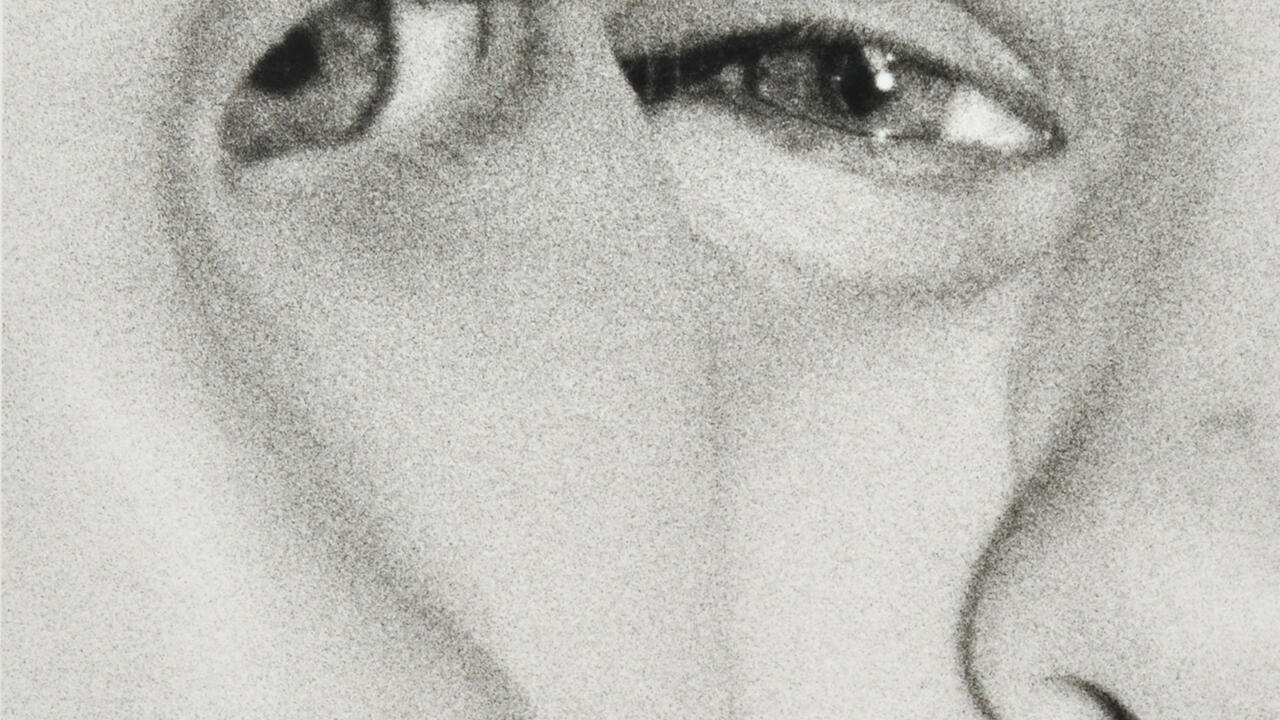

In this sparse, beautifully installed show ideas seemed so initially understated it took a while to realize how oddly animated these paintings actually are. Except for the sombre image of a cage, Within (all works 2001), surfaces shimmer as though diluted with a summer haze, the almost uniform paleness of the palette evoking a sense of something whispered, hinted at and possibly distorted in the telling. Shadows litter the surfaces like dull moments on bright days; look closely and they are almost photographic, but in a distanced way, as if the image had died twice and been resurrected as an appealing stain. The titles emphasize the peculiarly symbiotic relationship that flows between the paintings. Whereas some of the titles are purely descriptive - an image of a flock of pigeons is titled Pigeons, and Bending Over depicts someone bending over - others are more oblique. An image of a lone pigeon, for example, is entitled Dracula, and a portrait of an unidentified man goes under the title of Rumour. Constantly wrestling with the tension between a picture and the words we use to describe it, Tuymans seems as interested in freeing up the possibilities of painting per se as he is in creating an idiosyncratic language built from the solid foundations that have made good painting such a durable medium.

'Rumour' is a slippery word which implies a slippery method of gathering knowledge. By its very nature a rumour possesses an ambivalent relationship to the truth, a relationship that can hinder as much as encourage communication. It is, in other words, an apt metaphor for painting, a medium that despite enduring years of character assassination still somehow manages to hold its head high. Like the poor cousin of Picasso's peace dove, the pigeon has not only suffered similar indignities but has also, like painting, been employed as a messenger - one that more often than not has been waylaid, shot down or declared dead before the message is delivered. If this seems a rather precarious, even silly simile, it is the almost wilful aura of intrigue in Tuymans' paintings that encourages such readings.

After enjoying the sheer physicality of these pictures, connections begin to make themselves felt. Obviously, they depict everyday things transformed into exhausted symbols, which, reanimated and then lumped together, rather crudely imply links between vision and freedom (eyes, birds and cages?). But just when you think you've got it - as if painting were a puzzle waiting to be solved - your logic is thwarted by Bending Over. The smallest work in the show, it is also the most disruptive. Some of the paintings here draw their strength from the surrounding pictures - isolated, the portrait of the man or the three eyeballs might not be so interesting. This painting, however, would be compelling whether alone or on a crowded wall. The drawing is solid, the acerbic green paint bluntly and beautifully applied, the composition unsettling. It depicts someone - their gender unspecified - bending over, their back rising from their pants like a tired monolith. It should be a simple image, but it's not. Perhaps it's the green, the kind of colour that recalls carsickness, or bodies found in ponds or the clammy underside of a wet leaf. Or perhaps it's the posture, which, forever concealing the identity of the subject, implies a humiliating body search. In any case, it's a great picture, its economy of means perfectly suited to its many possible readings.

Which is pretty much what you can say about this show as a whole. Tuymans employs a language that initially appears ordinary, even a little worn out, but it's neither. He proves that words and images, however tired, can still, in the right hands, be woken up.