Lynn Hershman Leeson’s Game of Doubles

The artist’s far-seeing experiments with digital avatars and viral antibodies help us better understand ourselves

The artist’s far-seeing experiments with digital avatars and viral antibodies help us better understand ourselves

I first met Lynn Hershman Leeson at a restaurant in North Beach, San Francisco, four years ago to the day as I write this. My mom was dying then; death rips a hole in time, cutting through the calendar. That afternoon, the sky was an aching blue. The artist’s hair was a buoyant, red-brown bouffant and a ring of keys encircled her wrist. A handbag lay at our feet and, from it, wrist jingling, she retrieved a painting by Yves Klein. The size of a postage stamp, it glowed in the artist’s trademark royal blue. Hershman Leeson spoke of Klein’s quest for the sky and the sea, for something boundless, as well as of utopian values, the internet and the online virtual world Second Life, which hosts an archive of her work (Life Squared, 2007).

Players of Second Life can tour a re-creation of Hershman Leeson’s installation The Dante Hotel (1972–73), which ran for nearly ten months in Room 47 of the titular inn. Visitors could ask for the key at the front desk and, upon entering the room, would find two women in bed: wax figures, whose faces were both modelled on Hershman Leeson’s. Elton John played on the radio and a recording of Molly Bloom’s softly moaned dialogue from James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) could be heard in the background. With its undertones of sex, voyeurism and violence, the work was eventually impounded after a startled visitor called the police. Decades later, a team of engineers at Stanford University reconstructed the installation for two exhibitions in which Life Squared was accessible to both gallery visitors and players of Second Life. These virtual viewers could visit a room containing documentation of the original installation, wander through the hotel’s floor plan and enter galleries archiving Hershman Leeson’s other work. They might also encounter the artist, who would spend time in the virtual installation as an avatar named Ssofft Ware. Yet, even in its original incarnation, as an immersive staged environment, The Dante Hotel operated as a virtual space before the term was ever applied to the digital realm.

During the 1970s, Hershman Leeson and many other women artists worked outside of traditional galleries and museums, in part because the art world sidelined them. However, unconventional spaces also allowed Hershman Leeson to explore new media and new themes. In 1975, for instance, she staged a work in a casino, Lady Luck: A Double Portrait of Las Vegas, in which a circus performer and an identically dressed wax model took to the craps tables. The human woman, betting on intuition, lost all her money; the wax figure used randomly generated numbers and won.

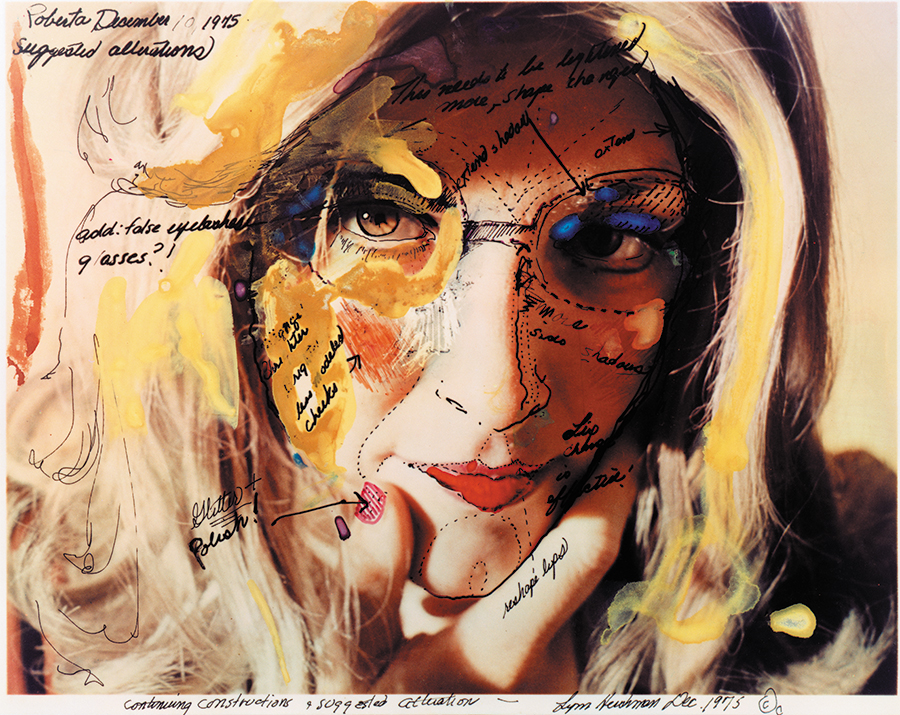

For ‘Roberta Breitmore’ (1973–78), her longest-running project, Hershman Leeson inhabited an alter ego for several years. Breitmore had her own driving licence, address and therapist, and sought roommates and boyfriends in newspaper classifieds. Documentation of the series includes a photograph detailing the paint-by-numbers guide to Breitmore’s make-up, alongside instructions on how to act like a woman. Long before LARPing, Breitmore was a vehicle for Hershman Leeson – and, eventually, the other women who performed the role – to pose questions about female identity and the performance of gender. Doubles recur throughout her work: as avatars, alter egos, role re-enactments and restagings. The artist even added to Life Squared an avatar of Breitmore, who talks to visitors in the game.

The day we met in San Francisco, Hershman Leeson told me that Second Life had begun as a virtual collectivist society, but had become gradually more sinister, populated by avatars of prostitutes and murderers, mirroring the internet’s descent into capitalist exploitation. Now that, in the midst of a pandemic, our lives have contracted to our screens – a contradictory confluence of social media and social isolation – Hershman Leeson’s virtual games and use of digital technology to explore themes of loneliness, voyeurism and surveillance appears remarkably prescient. Take Lorna (1984), for instance, one of the first interactive games on laserdisc. Its titular character is an agoraphobic woman who never leaves her apartment. The more television Lorna watches, the more nervous she becomes. When the work is shown in a gallery, visitors play the game in a re-creation of Lorna’s dim bedroom. Lorna has alternate endings, depending on how the viewer responds to various questions and prompts. Its inbuilt voyeurism – our spying on Lorna – was a harbinger for the world to come.

As technology evolved, so did Hershman Leeson’s use of it. The Dollie Clones (1996), a pair of telerobotic dolls with surveillance cameras for eyes, streamed footage to a website controlled by online viewers. Created within two years of webcams becoming commercially available, the dolls (one of whom was dressed as Breitmore) seemed to presage the way the ‘internet of things’ – watches, keys, household appliances, children’s toys – would begin spying on us.

For the 2009 work No Body Special, Hershman Leeson photographed women wearing outfits by the French fashion designer Jean Patou as they roamed around San Francisco. The images were posted on Flickr; the clothes appeared on a Second Life avatar and the artist used Google Maps and mobile-phone images to track them across the city. Ten years later, with such surveillance the subject of ongoing international debate, her film and interactive installation Shadow Stalker (2019), at The Shed in New York, detailed how data mapping and algorithms track us all and, in particular, how the police weaponize them to target people of colour. The work’s ‘shadow’ is a visualization of the data that follows us as we move through the world. The film’s haunting voice-over informs us that data has surpassed oil to become the world’s most valuable commodity. ‘We must decide what we will become,’ the narrator intones, ‘prisoners or revolutionaries.’

In early April, Hershman Leeson and I meet again, this time via the video-conferencing platform Zoom. Wearing beige, she sits before shelves of books and unfinished projects. I mention Zoom’s own privacy issues and the way her work has always bridged bodies in real and virtual space. She dips her head towards her screen and likens the way data works to COVID-19: ‘We don’t know how it’s hitting us or what it will cause. More and more, we are losing control of who we are and our identity is being virtualized and contaminated, just like the globe, like the virus is this contamination through connection.’ I repeat those last three words. ‘It doesn’t just have to be dystopic,’ she continues. ‘We had collective traumas in the past, but we didn’t have the internet; now, we have the connectivity to try to understand this in profound ways.’

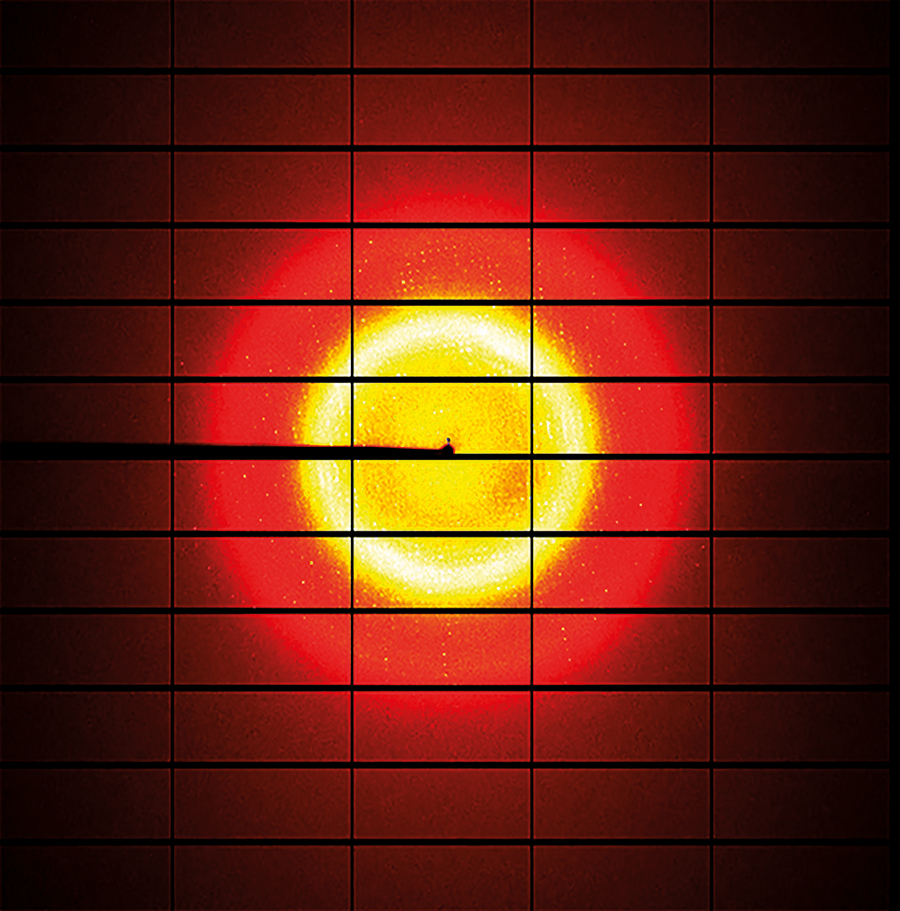

This quest for human connection and healing is key to Hershman Leeson’s work. Although Breitmore and Lorna were reclusive, searching for fulfilment within their own sealed-off worlds, their creator has a fundamentally optimistic view of technology. When we met, she spoke about the importance of San Francisco to her work, and her participation in the 1960s Berkeley free-speech movement that inspired the technological utopianism of early computer programmers. Over the last decade, she has been exploring biotech in her work, collaborating with Harvard geneticist George Church and biomedical researcher Thomas Huber at the pharmaceutical company Novartis to produce viral antibodies. In 2018, Huber and his team assembled LYNNHERSHMAN from amino acids selected according to the letters in the artist’s name. Its counterpart, ERTA, was named for Breitmore. In this sense, both antibodies are doubles.

An antibody ‘inverts identity, it attaches from the inside out’, Hershman Leeson told curator Sabine Himmelsbach in a catalogue interview published on the occasion of her 2018 exhibition at Basel’s Haus der elektronischen Künste. ‘It is […] a reframing of the biological essence of who we are, and is also a device to attack toxins, which essentially is what artists do anyway.’ This idea of art’s special power is one we all need now.

In the 1990s, Hershman Leeson used the word ‘anti-body’ to describe Breitmore; now, the artist calls her a ‘negative positive image of reality’. Hershman Leeson’s play of doubles is a kind of game that mirrors the essential division of modern life, between our physical bodies and our online presences. She reminds us that both are subject to the laws of patriarchy and the state, but also fertile ground for reinvention. Although Hershman Leeson officially parted ways with Breitmore in 1978, following an exorcism in Italy, the avatar keeps reappearing in her work – like a ghost from the past bringing news of the future.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 212 with the headline ‘Double Dutch’.

Main Image: Lynn Hershman Leeson, Lady Luck: A Double Portrait of Las Vegas, 1975, Circus Circus, Las Vegas. All images courtesy: the artist, Bridget Donahue, New York, Anglim Gilbert Gallery, San Francisco, and Waldburger Wouters, Brussels