Made in LA

Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, USA

Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, USA

Dorothy Parker once described Los Angeles as 72 suburbs in search of a city. It’s that multi-facetedness that makes the idea of a biennial here all the more tricky and presumptuous. As both a premise and title, ‘Made in LA’ has been critically debated since the exhibition’s debut in 2012. Questions were raised as to whether such a localized biennial was needed. Yet this seems the wrong line of inquiry – the meat of the issue is more in why so many artists choose to work here, and how they do so. As one of the many recent New York transplants getting to know the deeper recesses of the city, its tribes and micro-histories, these questions have been on my mind lately. ‘Made in LA’ is, at the very least, a show in which the many faces of the city can take to the stage in turn.

The biennial took over the entirety of the Hammer Museum’s galleries and courtyard, elbowing out its permanent collection. At its helm was the Hammer’s Chief Curator, Connie Butler, and writer/curator Michael Ned Holte. In 2012, the exhibition splayed out across three separate venues and included 60 artists. Bold and somewhat unwieldy, that show made an effort to tie down specific themes, or watchwords. In 2014, the 35-artist exhibition was much tighter and more pared-back, but no less ambitious. Notably, it featured more women artists than men. Although officially without a theme, shared sensibilities and a mood emerged; a certain lush sadness punctuated by fanciful moments, a feeling that is not unlike one that comes when exploring the streets of LA. Collectivity and collaboration too often become catch-all terms for loosely themed exhibitions. In the case of ‘Made In LA’, it was less curatorial talking point than fact; in Los Angeles, people, and even institutions work together in ways that are rare in other national and international art centres. Perhaps it’s a survival strategy. With LA a few degrees to the left of being an art commercial capital, smaller platforms tend to thrive, forever in the shadow of the city’s gleaming entertainment industry. Small networks do big things.

‘Made In LA’ highlighted several ‘micro-organizations’. Public Fiction, an exhibition venue and quarterly publication founded in 2010 by Lauren Mackler, was given free reign of a lobby space. Joined by writer Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer, Mackler created a structure of six episodic exhibitions, performances and writing contributions, featuring artists such as Eric Wesley and Darren Bader, and writers including Chris Kraus and Becket Flannery. The curiously complicated and expansive programme unfolded over three months at the Hammer as well as at Public Fiction’s home base, a storefront in the Highland Park neighbourhood of east LA.

Not far from their base, in Eagle Rock, sits The Los Angeles Museum of Art, a three-and-a-half by four-metre shed-cum-exhibition space founded, programmed and designed by artist Alice Könitz. LAMOA, which has been showing small exhibitions of LA artists in its driveway venue for the last two years, was transplanted to its own room in the museum. Könitz designed modular hanging and display structures recalling Russian Constructivist exhibition design, only grittier and, for me, more charming. LAMOA’s exhibition within an exhibition included work by 23 artists, ranging from Tony Conrad, to Judith Hopf, to a mask used by the Bread and Puppet Theater in 1973.

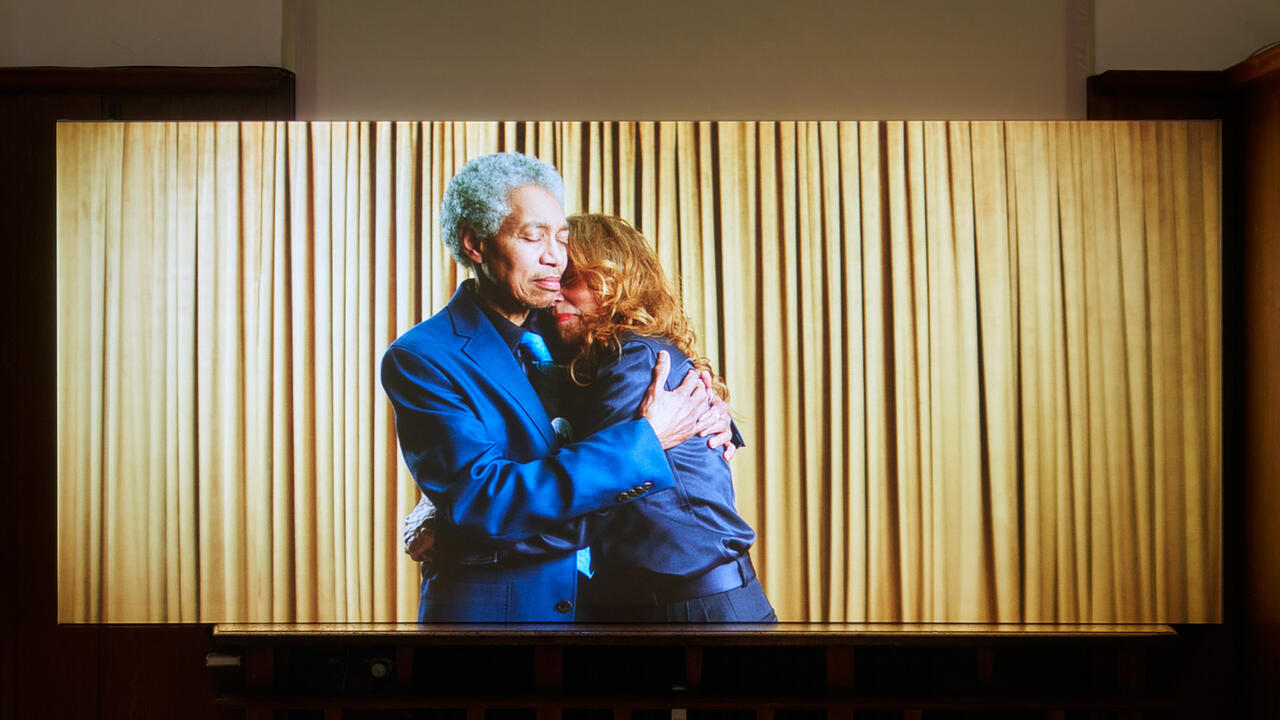

‘Made in LA’ was animated by a bevy of performances. The most visible was the Gold Stage, a temporary home in the Hammer’s inner courtyard given to Jmy James Kidd, the founder of Lincoln Heights dance space, Pieter. In addition to scheduled performances programmed by Kidd, the stage became an open rehearsal space for the larger Pieter community, making dancers stretching in the sunlight of the courtyard a common sight. The performance styles varied but seemed a collective homage to prolific LA-based dancer Simone Forti, with her focus on the physicalization of emotions and the flow from relaxed to ecstatic states.

It is the afterlife of performance, though, which seemed central to many other works, including those by Emily Mast. The choreographer’s energetic and absurdist performances as part of ENDE (Like a New Beginning) (2014) were spread throughout the museum as installations occasionally activated with unannounced performance and video. Highly scripted and theatrically playful, the performances featured an organized chaos of players, from children to the elderly, repeating simple gestures and manipulating props including baguettes, lemons, buckets and boxes. Stylistically, they echoed another LA artist, Guy de Cointet, and his Structuralist-inspired, prop-strewn stage productions. When they weren’t being used as part of the act, Mast’s objects operated as sculpture, an interesting solution to showing performance in a gallery.

Performance and humour were at the core of Piero Golia’s charming monumental sculpture The Comedy of Craft (Act 1: Carving George Washington’s Nose) (2014). As the title suggests, each day, a group of workers carved a large block of Styrofoam to produce a scale replica of George Washington’s nose as rendered on Mount Rushmore. Though confined to a gallery here, the performance work of Jennifer Moon undoubtedly comprises the artist’s entire life. She exhibited work from the series ‘Phoenix Rising Saga: Part 2’ (2013), which starts with a hallucinatory promise she made with an entity, ‘Bob’, to give up love for the sake of her career. The works at the Hammer are part of her attempt to nullify that deal; that is, to find the ever-elusive balance between love and work. It’s a self-help fantasy in sculpture and text, the works winking hard at kitsch Californian New Age ideology, as with A Story of a Girl and a Horse: The Search for Courage (2014), a digital photo of Moon riding a unicorn off into the sky. It is in the work’s more down-to-earth moments that the artist reveals some of her vulnerability, however. The Book of Eros (2014), for example, is an over-sized book documenting her love affairs, which designed to resemble Dungeons and Dragons score cards for characters. The backstory of her project, as read in the catalogue, describes how Moon’s work was influenced by her time spent incarcerated in a women’s correctional facility in California in 2008–09.

Moving-image works in the exhibition were particularly strong. Mariah Garnett’s video, Full Burn (2014), follows former soldiers turned stuntmen, one of whom specializes in setting fire to himself. His plain-spoken manner in documentary-style interviews about his current job are intercut with his descriptions of active duty tours in Iraq, leading the viewer to the horribly fascinating suggestion that his movie work constitutes some kind of immersion therapy to combat PTSD.

Poet and artist Jibade-Khalil Huffman’s room-sized installation The Parts of Speech (2014) layered slide projections of garden landscapes and street scenes with short disjointed videos of characters. Brief hints of narrative suggested a story that built only to collapse back in on itself, as if falling into its own visual lushness. The Parts of Speech expresses a roundabout quality, balancing mundane familiarity and beauty that seems strangely suited to LA in particular.

Documenting the periphery of a city’s culture, Wu Tsang presented an excellent two-channel film, A day in the life of bliss (2014); a sci-fi drag story starring the performer boychild, with her highly charged approach to dance. Shown on two screens opposite mirrors, the work surrounded the viewer. I could have seen this mirrored over a whole floor. Tony Greene: Amid Voluptuous Calm was an exhibition-within-an-exhibition, curated by David Frantz of LA’s ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives. The work of Greene, who died of AIDS-related complications in 1990, was paired with artworks and activist ephemera of his contemporaries in the 1980s, including extreme performance figures Ron Athey and Bob Flanagan. Greene’s project was a striking and controversial departure from that of his peers as he painted decadent patterning on vintage photographs of male pinups. In the exhibition, Frantz teases out the edges of a turbulent social history that’s often only heard of in the contexts of San Francisco and downtown New York.

‘Made In LA’ was strikingly diverse and its many through-lines and alliances were oblique and difficult to pin down. It seems fitting that these connections should be sketchy and speculative, reflecting something of the city itself. Many of the artists included seem to find inspiration in the city and its discontents; its sprawling and vast anonymity, which is nonetheless more human-scale in its culture and lifestyle than many major cities. For an artist, this is partially because the visual arts are not the main game in town. Living in the shadow of the Hollywood sign can have its advantages, allowing artists the distance to step back and get on with their work. Relatively less pressure and competition of the kind that comes with a bustling commercial gallery system has numerous advantages – as does living in communities forged by the heady idealism of art school. (Numerous artists first move to LA to attend one of its highly rated art schools, with their reputation for building deep mentor-student bonds. For the many that stay on after their studies, being a teacher is synonymous with being a working artist.) Even as the number of galleries keeps growing along with the diversification of sources for art world capital, the LA vernacular remains palpable and the Hammer remains an institution atypically close to the street.