Mark Roeder

Sister, Los Angeles, USA

Sister, Los Angeles, USA

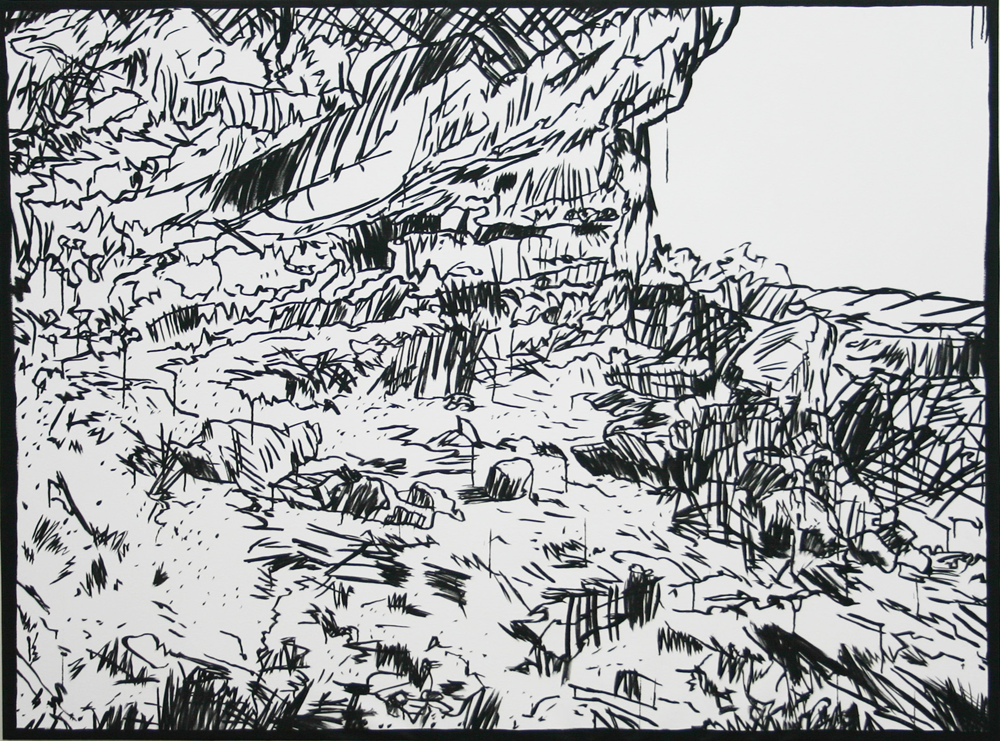

For Mark Roeder, pathos and bathos collide in the Californian landscape. There’s an earnest sadness and nostalgia in what he calls in one of his black and white, cartoonish paintings his ‘Individual Psychical Space’, but it’s a sadness that moves quickly from the sublime to the ridiculous, bathed in a hellish half-light of self-awareness. The paradisiacal feelings about California felt by this contemplative artist are undercut by his self-conscious awareness of how absurd such feelings are. Each of the paintings and collages included in this show (titled ‘California Landscape Paintings’) recall places of personal significance for Roeder (a surf spot, a hike), along with a subtle dig at the humourless history of landscape painting in the state. Each image is painted twice (though one is torn and half is collaged); each one emanates, for all their earnestness, a tongue-in-cheek conceptualism. They’re built to fail.

Failure has been part of the California psyche from the beginning. The Spaniards who named the state apparently picked up their knowledge from a 16th-century book describing a fantasy island ruled by a naked, black tribe of Amazonians who beat off invaders with gold weapons. In Roeder’s 2009 painting Noncommittal, Antipainting (Multidimensional – Secret Spot #2, with Attached California Amazons), the landscape is overlaid with a collage of half-naked African dancers; the artist has scrawled along the bottom of the image the words ‘California Island Dream’, as if he’s reminding us never to forget the mythic Amazonians the Spaniards failed to find.

Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer, the curator of the show, invokes Samuel Beckett in her refreshingly lyrical press release, quoting the famous lines from his late, short text from 1983, Worstward Ho: ‘Ever tried. Ever Failed. No Matter. Try Again. Fail Again. Fail Better’. Beckett’s tersely worded prose-piece bemoans the failure of speech to represent thought; one must resign oneself to speaking badly. But unlike the landscape painters of the early California wilderness (a set of earnest young artists with Impressionism rattling through their heads) that preceded him, Roeder is fully conscious of the collapse in meaning even as he’s making it.

One mode of art (and fantasy) is to distract us from reality, as Roeder writes in another text piece included in the show: ‘The content of message in this “work” is misleading and intends to redirect your attention from your “real life” problems’. The collage is backed not by California but Tahiti, Gauguin’s inspired paradise of noble savages painted with thick black lines. If the self-stated point of the work is to distract us, it cannot really do so by telling us. It’s just another tragicomic canceling out, typical of Beckett but met in a dreamy California landscape: ‘I can’t go on. I’ll go on.’