A Matter of Material

Sergej Jensen’s exhausted, expressive paintings, gallery interventions, rare films and moody music

Sergej Jensen’s exhausted, expressive paintings, gallery interventions, rare films and moody music

Here is a list of things that might be thought of as Sergej Jensen’s materials and methods: a range of beige linens, cotton canvas and Autumn-toned fabric leftovers fit for a bazaar; stains and other traces; wavering sewing machine seams and hand knitting; the idea of a painting’s surface as the place for a mishap or an event; the visual equivalents in colour and surface treatment of drones, chords and discords; cloudiness, sparkles and glimmers; smoothness with a rough edge; and the infliction of careful damage. This list is out of order and incomplete. I could add the electrified air around any given one of his abstract paintings, the intervals and changes in perspective that occur when you line up a number of them with heterogeneous formats, and lastly, a sense of space incorporating not just the display possibilities of the walls, but also the ceiling and floor as flat compositions of abstract fields. What’s also missing is a kind of practical knowledge of art historical precedents; an obvious sensibility for all of the effects, techniques and tricks of the trade inherited from abstract, colour field and minimalist painting of the last century. His works can variously recall things like a random detail of a Paul Klee painting, a washed-out and sewn version of a Hans Hoffman, a ragamuffin take on Blinky Palermo’s fields of sewn fabric ‘Stoffbilder’, or works by some forgotten New Yorker from the late 1970s. Such is the visual echo chamber of abstraction that a hundred other references might also equally do.

All of which might seem like a lot of material and art baggage to handle, and it partially accounts for why some of Jensen’s most recent paintings seem to be falling apart at the seams, frayed, fading, roughed-up or as near to nothing as possible. Untitled Silver (2008), for instance, comprises an ultra-thin monochrome wash of silver pigment on a rye-bread-coloured linen canvas about the size of two people lying close to each other and a couple of easily missed, miniscule indigo-blue drops of paint. Maybe these small disturbances are stool pigeon signs of a certain amount of cultivated indifference, or just accidental gestures from a wet paintbrush on its way to a different destination. If the light changes, the silver surface renders something equivalent to mood swings. In some settings, you could imagine this painting glittering like a rectangular sequin or the life of a party; in others, looking cloudy, mute and drawing attention to itself by hanging out in a corner. The beginnings of an image in this painting and others, such as Nothing (2007), an uneven yellow wash with a bit of glitter stuck to it, seem fugitive. It’s almost as if it has failed or refused to appear in full. In any case, it’s not on top. It’s soaked in or through and has partly dissipated in the process. Maybe these paintings prefer to be atmospheres, rather than modern, full-frontal surfaces.

It seems to me that Jensen’s paintings don’t want to graduate from the school of high modernism, but still need to be enrolled in some sense, if only in order to be perceived as dissonant, talented dropouts. Along with the occasional ochre rainbows and diamonds, his works are dominated by corrupted, decorative, wavering grids and fields, along with crooked stripes and fuzzy shapes scattered on minimalist formats. Sometimes his works’ wry, winking titles such as Men with hats (2006), an abstract composition of camouflage-coloured triangles arranged like two towers of pocket handkerchiefs, or Das hab Ich nicht so gemeint (I didn’t mean it like that, 2002), a ring of iron-on patches, indicate that his work isn’t a brand of po-faced neo-formalism. Sometimes it’s his materials that suggest playful sarcasm. Take for example his elegant compositions made with linen moneybags purchased on ebay, like Tower of Nothing (2004); or those sparsely decorated with real bank notes like Untitled (Money Face) (2006), a cash sketch whose nose has obviously once been rolled. More recently, the black monochrome painting on hemp, Untitled (2008), quite literally questioned its ‘support’ in so far as it warped and cracked its own stretcher bars in the process of drying. It was then exhibited in that tortured state of internal struggle with its own materiality.

Usually though, Jensen’s works aren’t so dramatic, and instead rely on minimizing the gesture and the potentially expressive, or worse, macho-coded bravado of wielding a roller or a brush. Some of his preferred techniques include bleaching his surfaces and adding cloth or knitted appliqués rather than actually applying colour. When he does use paint his shapes often resemble their anarchistic, everyday, poor cousins – plain old leak stains. Of late, he even made a few canvases that are simply primed surfaces and nothing else. With the work Untitled (2008), he took this reductive trend to another logical extreme: this ostensibly all-black tempera canvas is articulated only by scruffy knock marks so minimal that they can easily be misunderstood. Perhaps pretentious or irritating to the uninitiated, this kind of work entails an aesthetic rejection of perfect surfaces – the clean, dust-free and neurotically hygienic feel demanded of much contemporary art. There is a tradition of this kind of unorthodox mark-making in painting, for example Edvard Munch’s paintings left exposed to the Norwegian elements, Carl André’s trodden-on floor works and Andy Warhol’s decorative, relieving painting series Oxidation and Piss (1978), although as far as I know, Jensen’s works don’t directly involve the weather, the wandering general public, or a third party hunk.

Nevertheless, some of Jensen’s marks certainly look arbitrary – it’s not unkind to suggest that some of his works might have been made at a certain remove, as if by instruction, assistants, accident or a combination of those things. In this sense, his paintings have been conceptually welcomed to the ground. Arguably, conceptualism is the missing link in an understanding of his work, the one that enables it to be viewed as a break, not as a nostalgic revisiting or exercise in neo-modern mannerism. Thinking along these lines means seeing his paintings in the light of work like Lawrence Wiener’s art-by-instruction piece Two minutes of spray paint directly upon the floor from a standard aerosol spray can (1968), or Stephen Prina’s analytical post-conceptual quotation of Wiener’s work as part of his exhibition When push comes to love, untitled (1999/2008). (By the way, Prina’s broad brush series of abstract wash paintings and charts Exquisite Corpse: the Complete Paintings of Manet [1988–ongoing], comes aesthetically closer to Jensen in terms of a conscious gutting out of the image and emphasis and analysis of frames and formats over pictured or painted spectacles.)

But perhaps it’s through his hangings and interventions in art spaces and his own idiosyncratic, impure photographic documentation of these efforts that Jensen really exposes his thinking about art and painting’s part in it, as well as the idea of context and space as a kind of extended canvas. Paradoxically, Jensen’s paintings perhaps wouldn’t work with too much visual or physical chaos around them. His paintings, and their off-the-wall cousins like rugs woven from shopping bags (such as Untitled, 2004) and patchwork ceiling cloths, are both reliant upon and antagonist to their ideal environment – namely, chic white-cube spaces. This produces the strange friction involved in any co-dependency around his work and exhibitions. At its subversively sartorial best, Jensen’s work addresses how to make an exhibition in a way that is akin to dressing a fancy room in rags, or injecting a vagrant private into a pristine public. His not-on-canvas actions are crucially important here. In 2004 at Galerie Neu in Berlin, he had a fireplace installed in the white cube. Part way through the show, he redecorated the space by swapping some works, adding a couch, playing some live music and projecting a new film. In his most recent solo exhibition in the same gallery, ‘Pictures and Paintings’ (2008), he had the gallery clear out their office and remove the shelves, table and other gallery furniture, therefore making it at least symbolically impossible for them to conduct business as usual. The vacation of the space also revealed dust and grime (pointedly not cleaned-up) behind things. This action wasn’t designated as a work, nor particularly commented upon – it was simply a laying bare of sorts.

At the 4th Berlin Biennale in 2006, he transformed a small apartment into a waiting room with paintings on the walls, and the kind of chairs you might see in a psychologist’s office. He also blocked the windows with white fabric screens and hung a patchwork canvas from the ceiling. Together the ensemble conveyed a sense of enclosed wellbeing in limbo, a place between feeling good and actually being healthy. The same year, at White Cube gallery in London, he had a window knocked into one of the main display walls of the gallery, positioned sardonically (and generously) in a row with his paintings. At that show the white cube was given warm ambient spot lighting to give his paintings friendly auras. And finally, most recently in the Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich in a collaborative exhibition with Henrik Olesen, the two consciously played up to the turn-of-the-millennium, gargantuan, white and concrete po-mo architectural setting by fitting and bending the bill in an ambivalent, grubby way. The artists installed a combination of works including Olesen’s wonky polystyrene milk carton accompanied by Sol LeWitt remakes and Jensen’s mute and injured looking recent canvases. Aside from all of these interventions in spaces in a single, thus far unique painting brings Jensen’s ideas of what happens when his paintings come home to roost. Untitled (2008), is a raw canvas with photographs documenting a previous exhibition glued onto it in a loose grid. For his catalogues Jensen himself has played with the photographic documentation of his work preferring droll imperfection to flawless lighting, giving a sense that the paintings have been somehow abandoned to spaces in another time and that reproductions can never do them justice.

Jensen also does other things like sing and play the guitar. He is a member of the bands Sud (with the artist Stefan Müller) and Da Group, and has released a number of 7" singles, one LP (‘Sud & Sud II’), and with artist Michaela Meise, a limited edition CD ‘Songs of Nico’ (Neu Acoustics, 2006). The latter homage is fragile, faltering, homemade-sounding, sometimes dark and aching. It sounds like an introvert’s private rejoicing about forever standing in a sad shadow. Just over a year or so ago I saw him perform together with artists Josef Strau and Stefan Müller. Jensen seemed sweaty, pale and emotionally stark naked. Their set was gripping and shocking. Their music was an indie-groaning from personal edges, and therefore, not so much hard to listen to as excruciating to watch.

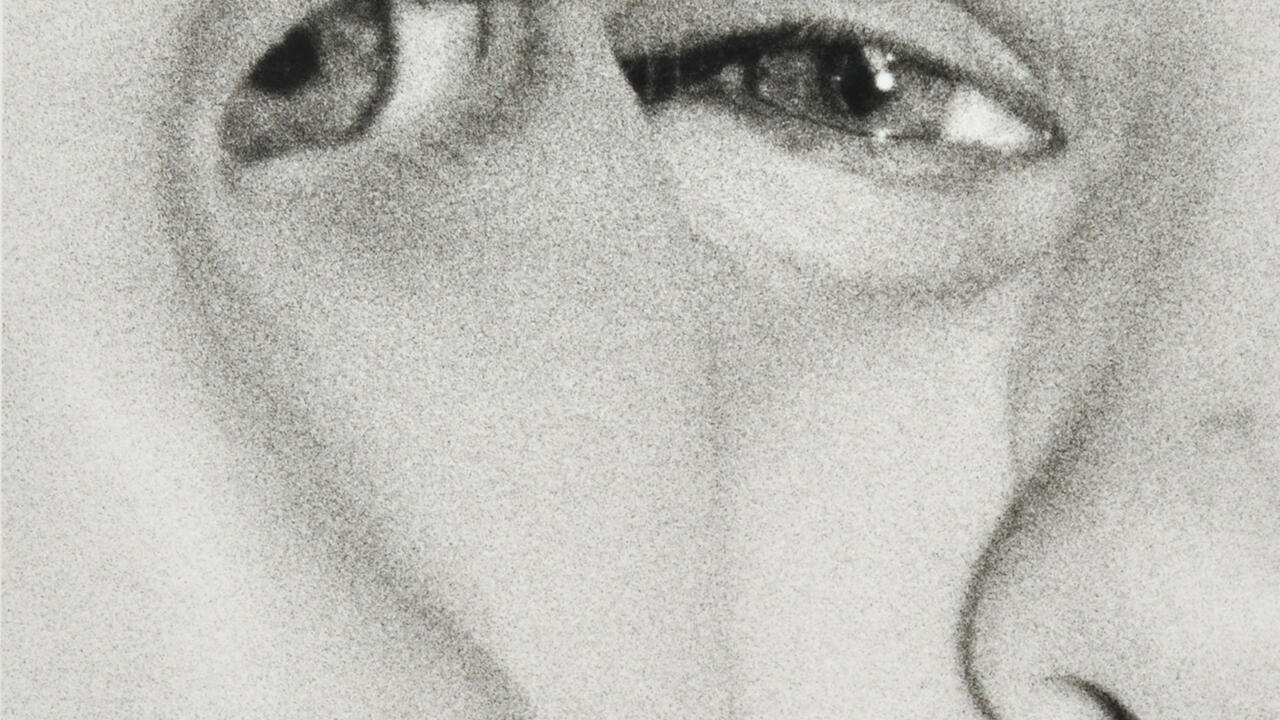

In his art as well as his music, subcultural glamour, extreme fatigue, an artful knowing and personal tenderness cohabitate. This might smack of neo-bohemian attitude but who wouldn’t subscribe to the idea of a life radically lived despite the pastiche it might involve? Jensen once made a Super 8 film in a Manhattan hotel room called Maritime (2004), which is something of a curiosity but not a complete oddity in his work (he has made the occasional video too). In low-lit black and white, the film documents the building and the room, in particular its circular, porthole-style windows and the movement of a curtain. It is an austere self-portrait, in which the artist alternatively glares and squints into the lens. Perhaps we should take this film as an example of how to look at his work: with a sense of the performance involved in doing so, and a spirit of nervous, self-conscious enquiry.