Megan Plunkett’s Past Life as a PI

The photographer recalls her experiences working undercover, and how they informed her art practice

The photographer recalls her experiences working undercover, and how they informed her art practice

A few years after I left school, I got lucky: an artist I’d been working for knew a private investigator in Los Angeles who was looking for an assistant. After successfully completing a trial assignment, I ended up working in the office for close to five years.

Private investigation is onerous – research-intensive, writing-heavy – and, during the summer months, I was also pursuing an MFA in New York. Nonetheless, it was an auspicious time. Being back in school, I was open to rethinking the boundaries of what I’d been doing in my studio practice. Recently, I was in a group show at DREI in Cologne, organized by the artists Angharad Williams and Gianmaria Andreetta, around Michel de Certeau’s theory of la perruque (the wig): what you can get done while otherwise engaged professionally, or how to steal time on the job. The main thing I did as a PI was research and write; I got very comfortable with legalese. Most of our research involved gathering and scrutinizing information that was largely publicly accessible. My bosses had access to massive databases, with subscription fees higher than the office rent, aggregated from different public-sector sources.

One of the biggest lessons of PI work is that you have to respond only to what’s in front of you and avoid preconceived notions. It’s an approach that’s been really helpful for me in the studio, and reminds me of Carol Bove’s query in her ‘Self-Help Guide for Artists’ (2017): ‘How do you create a way of being in the world that allows new things (ideas, information, people, places) into your life without letting everything in? […] You need to conduct an open-ended search that doesn’t overwhelm you with information and, at the same time, doesn’t limit the search in a way that pre-determines your findings.’

Informed by media portrayals, people’s understanding of the PI remit is usually incorrect – and, in LA, the spectre of film noir is inescapable. Our brains are hard-wired for meaning-making and dislike uncertainty. In a 2020 interview with Nightmare on Film Street, the filmmaker Brandon Cronenberg talks about how crafting two images that appear in proximity to one another opens the possibility for a third ‘that you see in your head, that isn’t on screen, that’s the real context of the scene’. When people found out I was working for a PI, their response was almost always: ‘Oh God, are you following people?’ Private investigation is a whole world with its own unspoken rules and hierarchies, and there are specialized PIs who only do surveillance: these are the types you hire to sit in a car all day, pee in bottles and watch one location.

At the moment, I’m working on a series of images starring my dog, Barry. He is so photogenic. When I adopted him last year, I became obsessed with the idea of photographing him in front of a billboard for the HBO show Barry (2018–ongoing), in an awkward forced perspective. Instead of waiting for a new season’s ad campaign to appear, I bought a bunch of bootlegged posters from the first two seasons with the intention of making collaged portraits of Barry. A mass of images – Barry, Barry posters, classic Lynchian red curtains, hands and more – has been piling up. I’m reminding myself of my PI research, when I would say: ‘I need to keep looking,’ but my bosses would intervene and say: ‘No, you need to start editing.’

As told to Diana Hamilton

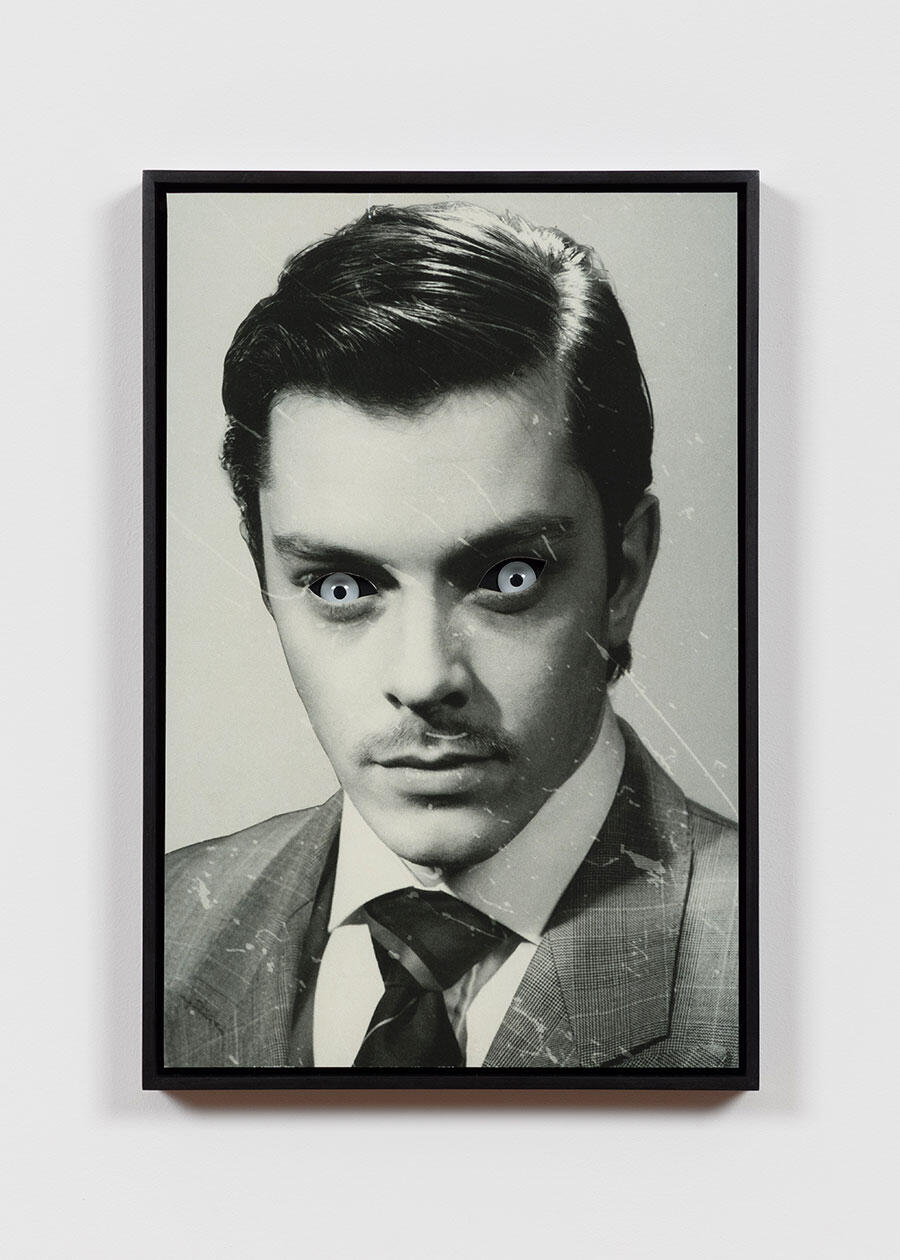

Main Image: Megan Plunkett, The Invader 03, 2021, digital C print on glossy paper, 27 × 41 cm. Courtesy: Emalin; photograph: Steve Bishop