Mierle Laderman Ukeles

Grazer Kunstverein, Graz, Austria

Grazer Kunstverein, Graz, Austria

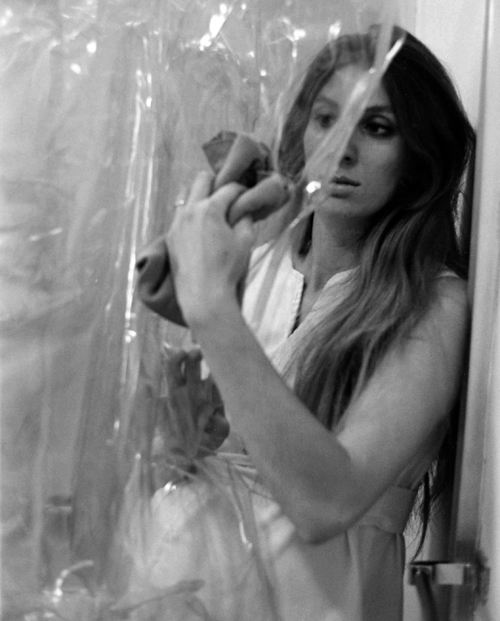

Krist Gruijthuijsen, the new artistic director of Grazer Kunstverein, wants to make some changes. In a mission statement, he says that from now on, the Kunstverein will see itself as an ‘agency’ for the production of art-related commonality or simply as a meeting place, meaning it is willing to break with traditional institutional structures. Fittingly, Gruijthuijsen’s debut exhibition, Maintenance Art Works 1969–1980, was the first major show in Europe of New York artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles, a pioneer of feminist Institutional Critique. This position was already clear in her Manifesto for Maintenance Art (1969), a text that acted as a prologue to this chronological solo show and that highlights the artist’s distinctive place within the avant-garde of conceptual art: ‘everything I say is Art is Art. Everything I do is Art is Art’, she notes under the heading ‘Art’, in the often-tautological style of the time (Joseph Kosuth, for example, labelled his conceptual work after 1966 ‘art as idea as idea’).

But instead of engaging in ritualized language games and actions, or embarking on the presumably enjoyable (because otherwise it would be unbearable) processing of self-imposed tasks and then continuing for decades as an artistic-maniac form of killing time (like Hanne Darboven, On Kawara or Roman Opałka), Ukeles resorted to activities that are part of ordinary everyday routine. In Maintenance Art: Personal Time Studies: Log (1973), she made meticulous notes of everything she did in a typical day. In her account, housework is treated the same way as activities considered artistic in a narrower sense. Expanding on this programme, Ukeles subsequently realized many performances based on cleaning and scrubbing at various art spaces, making portraits of the night workers at the Whitney Museum and asking them to consider their work as art for one hour. Her best-known project was Touch Sanitation (1977–80), commissioned by Creative Time, New York, for which she shook hands with over 8,500 New York sanitation workers, telling each one: ‘thank you for keeping New York City alive’.

Ukeles’ genius lies in the way she responded to the avant-garde pressure to innovate. Instead she used actions which, in themselves, are at odds with development and revolution – readable instead as measures for maintaining the ordinary everyday status quo. ‘If urinals and soup cans can be art, why not an ordinary activity like sweeping?’, asked critic David Bourdon in his review of a Ukeles show that appeared in Village Voice in 4 October 1976 and which has since become part of the documentation. Admittedly, Bourdon made his comment at a time when Andy Warhol, the younger of the two superstars he refers to, had already paid a literary tribute to housework. It is almost as if the penultimate chapter of The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again) (1975) was based on a telephone call with Ukeles, in which she explained the most pressing problems involved in cleaning. True to her principles, Ukeles took something that Warhol immortalized as anecdote, as an essentially dispensable phone call, and turned it into her main work.

Translated by Nicholas Grindell