More or Less

Radical minimalism from India and Pakistan

Radical minimalism from India and Pakistan

This September, Madrid’s Reina Sofía Museum will play host to the largest-ever retrospective of the late Indian artist, Nasreen Mohamedi. In 2016, the exhibition will travel to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art, as one of the inaugural events to be held in its new space, The Met Breuer. Mohamedi, who died in 1990, is celebrated for her minimal black and white drawings. Her renown has grown steadily over the last 15 years – she was the subject of a solo show at Tate Liverpool last year – and these two presentations will no doubt further raise her profile. Mohamedi deserves the attention. In the 1970s and ’80s, when figurative and narrative tendencies held sway within the Indian art community, she intuitively evolved an abstract, graphic manner of expression. It was through myriad explorations of the grid that Mohamedi’s aesthetic reached its apogee.

None of her contemporaries achieved the extreme formalism of Mohamedi’s work. A delicate suite of untitled drawings by Arpita Singh from the late 1970s shares Mohamedi’s reduced palette but Singh’s approach is looser: her tiny black strokes mesh together like a textile weave. Formally closer are the drawings of Dashrath Patel (Founding Secretary of the National Institute of Design in Ahmedabad), which he created as part of his daily mindfulness practice, although they’re not as complex as Mohamedi’s. The commonly held assumption that the aesthetic employed by these Indian artists was influenced by American minimalism is incorrect. The specific socio-economic conditions that guided the work of the American artists would not have had the same resonance for their South Asian counterparts, whose innovations evolved out of their own context. The little-known Pakistani artist Lala Rukh, who lives and works in Lahore, is one such example.

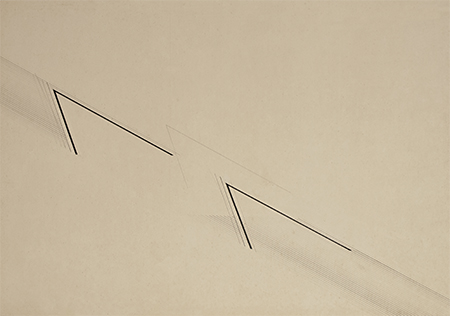

Lala Rukh trained at the Punjab University and, later, at the University of Chicago. After graduating in 1976, she returned to Pakistan, at a time of severe Islamization under the military dictatorship of General Zia ul Haq. Throughout the 1980s, and unaware of Mohamedi’s work until the end of that decade, Lala Rukh completed a series of dynamic life drawings that became increasingly minimal. Made rapidly using Conté crayon, Lala Rukh’s strokes are barely discernible. Although ostensibly abstract, when seen as a group, the works evoke the human body in motion. Since Orthodox Islam forbids the visual representation of the human form, this is abstraction with a political charge. Lala Rukh’s spare work was not well received in Pakistan; reactions bordered on the hostile.

In 1981, Lala Rukh began her life-long commitment to political activism, co-founding the Women’s Action Forum (WAF), a non-partisan Pakistani organization that fights violence and discrimination against women. She was also dedicated to teaching at the National College of Arts in Lahore, from which she only recently retired. While drawing is at the core of Lala Rukh’s practice, she also works with photography (‘Sand Paintings’, 2000) and audio recordings. For her series of drawings ‘River in an Ocean’ (1992–93), she used photographic paper, which lent her subtle, silver renderings of the ocean a haunting, luminescent quality. Lately, she has been working with fragile black carbon paper. Lala Rukh takes particular notice of the wrinkles and creases on the paper’s surface and includes them in her mark-making. The ripples of the paper become one with her elicitation of moonlight reflected off a nocturnal sea.

Lala Rukh has also developed a personalized form of calligraphy in her series ‘Hieroglyphics’ (1995–ongoing). In these modest drawings, language is abstracted and the notations intimate musical patterns (perhaps influenced by her father who, for many years, ran the All Pakistan Music Conference). She also mentions that being exposed to John Cage’s work while studying in Chicago had a significant impact on her imagination. Lala Rukh’s recent inclusion in the 12th Sharjah Biennial and ‘In Order to Join: The Political in a Historical Moment’ at the Goethe Institute and CSMVS in Mumbai (which travelled from Museum Abteiberg, Mönchengladbach), goes some way to situating her within regional and international frameworks, but more scholarly research is required. When asked by a collector why she works with minimal forms, Lala Rukh simply replied: ‘At night, you continue to look, then you start seeing so much more.’ It’s sound counsel for a perpetually distracted world.