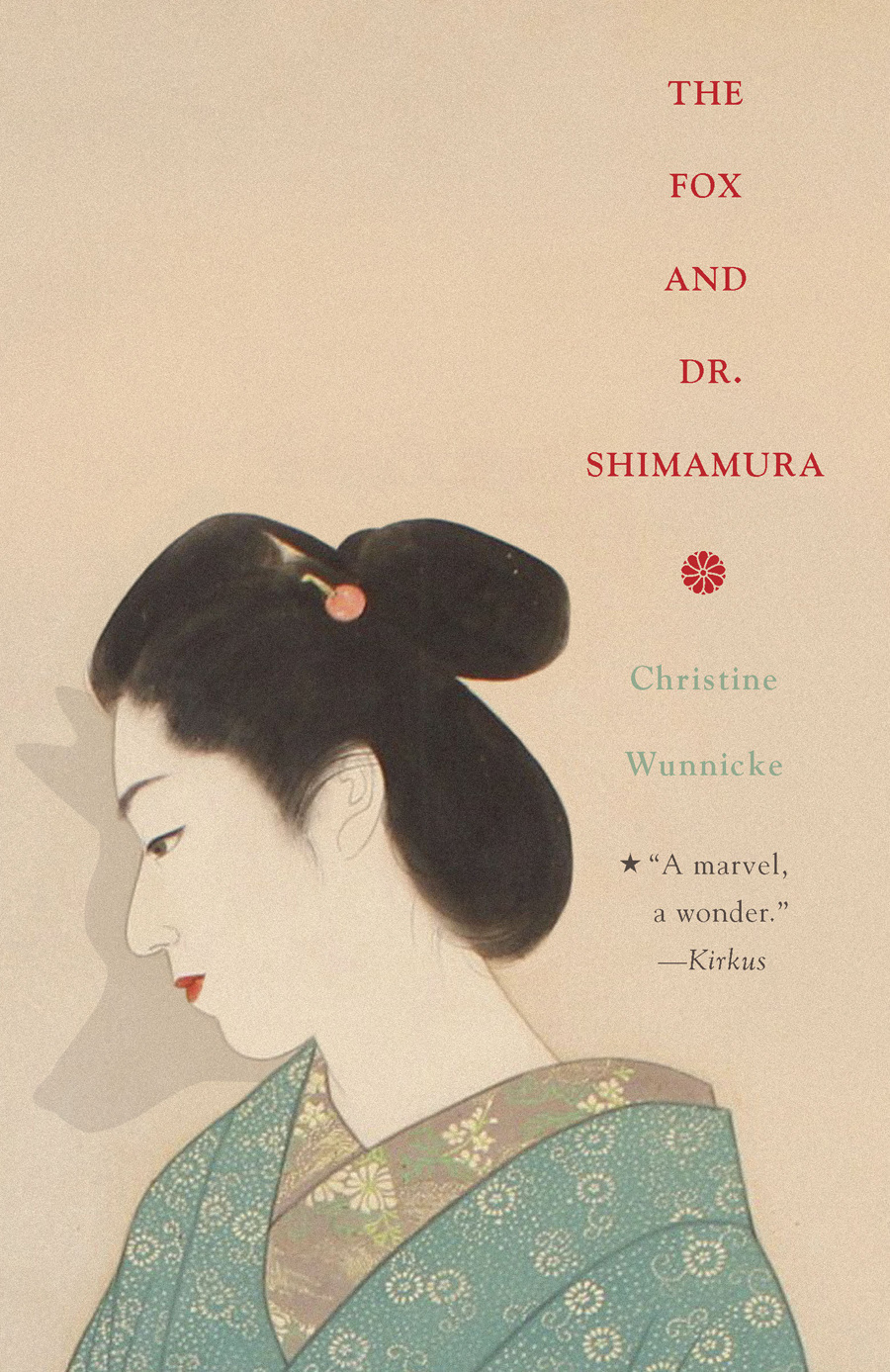

From the Mouths of Foxes

Christine Wunnicke’s book, The Fox and Dr. Shimamura, is a narrative of Japanese modernity spoken through divine foxes and a psychiatrist’s misfortune

Christine Wunnicke’s book, The Fox and Dr. Shimamura, is a narrative of Japanese modernity spoken through divine foxes and a psychiatrist’s misfortune

Dr. Shun’ichi Shimamura is dying. It is spring 1922. The eminent psychiatrist retired some years ago as director of the University Neurological Clinic at Kyoto Prefectural Medical College, where his outstanding achievement was the development of padded mats to line the walls of his most distressed patients. At his home in Kameoka, behind a European-style door in a similarly padded room, Dr Shimamura observes the passing of the seasons as he assembles notes for his magnum opus on the workings of memory. He is observed, in turn, by the four women who orbit him: his wife, his mother, his mother-in-law and a maidservant, ‘sometimes called Anna but more often Luise’, ‘brought along’ from the Kyoto asylum when the doctor left.

Christine Wunnicke’s The Fox and Dr. Shimamura (2015), newly translated from the German by Philip Boehm for New Directions, is a tribute to memory’s vagaries and digressions. The doctor recounts – half remembering, misremembering – his professional journey, from early fieldwork observing cases of kitsune-tsuki (fox possession) in young women in rural Japan through to his encounters in Europe with the luminaries of the nascent psychoanalytic age: Jean-Martin Charcot and his famous hysterics at the Salpêtrière hospital in Paris; Josef Breuer, mentor to Sigmund Freud, on the chaise longue of his Viennese consulting room. Wunnicke’s fictional narrative hangs off a slender biographical skeleton, furnished by two of the book’s three epigraphs: a page-length passage from the Parisian daily Le Temps, dated March 1892, and part of the abstract of a paper published about Dr Shimamura from a 1992 Japanese medical history journal. The former describes the appearance of an ‘Asiatic guest’ during one of Charcot’s characteristically dramatic public lectures at the Salpêtrière; the latter is titled ‘The life of Prof. Dr. Shun-ichi Shimamura (1862–1923). A distinguished psychiatrist of misfortune.’ A cursory google doesn’t turn up much further information about the good doctor. He existed, but his magnum opus, it seems, remained unwritten.

The grammatically ambiguous ‘psychiatrist of misfortune’ is apt here, since Shimamura is, by turns, doctor and patient: a Jekyll and Hyde of reason and superstition. Slavishly devoted to German medical science and the rational explanation of nervous afflictions (he carries a copy of the third edition of Wilhlem Griesinger’s Mental Pathology, 1867, everywhere he goes), he nevertheless exhibits certain inexplicable symptoms akin to those of the women he purports to treat. For decades, he has experienced a constant fever that, while neither life-threatening nor particularly inconvenient, ‘never dips below 100°F’. On the book’s opening page, this is attributed to a diagnosis of consumption, that most literary and tragic and European of diseases: of John Keats, Franz Kafka and Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain (1924). However, another, more fantastical explanation soon presents itself.

Enter the foxes. Supernatural creatures in the Japanese folk bestiary, they are familiars of the Shinto deity Inari, god of the rice and the harvest; their sculptures, in great numbers, guard his shrines. The book explains:

As a fox, Inari was as white as snow and had manifold tails. Long ago she had begun her divine life with four tails, and with each century she added a hundred more, so that today, in this sad, late epoch, she sported more tails than human numbers could count. At the same time she always had exactly nine. And at the same time, she was also a snake and a spider. She accompanied herself as her own servant – a winged, single-tailed fox. And at the same time she was a bodhisattva, or even seven, and also water, grain and land. She was a he as well as an it.

Foxes are shapeshifters. Like the selkies in the folk tales of the Northern Isles of Scotland, they sometimes appear as beautiful women, whom men marry and father children by. Their spirits enter young women beneath their fingernails or through their breasts causing delirium, fits, frothing at the mouth, an insatiable hunger for tofu, red beans and other foodstuffs delicious to foxes. Exorcism was the usual treatment for such afflictions, which remained a common explanation for mental illness in young women in Japan well into the 20th century. (The country’s first full-scale asylum was constructed in 1899; of the 2,558 people housed there during its first five years, 789 had been diagnosed with the broader class of mental disorders that included fox possession.1)

As a young physician, Dr Shimamura is sent into the countryside, Griesinger in hand, to diagnose and treat – using modern medical science – a number of reported cases of kitsune-tsuki. He is accompanied by a young student from a notable family and, in spite of himself, a rag-tag bunch of DIY exorcists (or would-be fox martyrs) that are described, unappealingly, as ‘receptacles’. These sorry figures try to tempt fox spirits out of possessed women and into their own bodies by various dubious means (ingesting the spittle of the afflicted; lying with soft tofu in their open mouths).

Shimamura’s final case is Kiyo, a particularly beautiful and eloquent young woman.

Shun’ichi Shimamura kept one eye on himself as he witnessed the outline of a perfectly formed fox appear, slanted, just below Kiyo’s collarbone. After a short rest the fox dodged to the side, then climbed into her neck and tried to force his way into her mouth.

Shimamura spends weeks with the girl until one night – in a sequence of events re-dreamed some years later, from the faux safety of Dr Breuer’s couch – she slips off her human skin and disappears, vulpine, into the moonlight. (The crisp, straightforwardness of Wunnicke’s language heightens the pervasive strangeness of this story. We might recall the immortal opening lines of Kafka’s Metamorphosis, 1915: ‘As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect.’) The girl wakes cured; Shimamura wakes changed. As his mother notes, in the pages of a biography that her son will never see because she writes in secret and immediately burns the pages: ‘The fact was that Dr. Shimamura had not only brought us a form of madness […] but also something that could be called soft and beautiful. […] And it was this new, soft, and beautiful quality that he carried with him ever after.’

On one level, The Fox and Dr Shimamura is a story about modernity – particularly the modernization of Japan. In the late 1800s, the nation was less than 50 years out of two centuries of sakoku – a period of extreme isolationism foreclosed abruptly by the arrival of American warships in 1853. The Imperial Commission that first sent Shimamura to Europe was part of a top-down effort to learn from the world that Japan had long kept at its margins. The fascination was reciprocal: European capitals in the late 19th century were feverish with Japonisme. Shimamura’s appeal to the ladies of Paris was not only down to the spirit of the fox that he may or may not have received in the Japanese countryside, but also a more routine exoticism. (‘Soft’ and ‘beautiful’, after all, are adjectives routinely applied to East Asians in Western thought, then as now.) Europe, at least superficially, represents science, progress, the detached observation that is legacy of the Enlightenment (even when its methods are brutal; in his first job while in Paris, Shimamura is made to guillotine animals to measure their reaction times). The Orient represents superstition, the inexplicable, the bodily. The sexual. Beliefs that cling. One is the domain of men; the other of fishwives. (Kiyo is the daughter of a fishmonger.)

But the foundations of European confidence in the scientific method are revealed to be shaky. Charcot is denounced as a showman and Breuer a manipulator. Freud is dismissed out of hat: ‘The analytic conversation as a healing method for traumatic hysteria […] is of little use for Japan, as it contradicts our sense of politeness, and besides it takes too long.’ How different, really, are the choreographed arcs of Charcot’s grande hystérie and the subcutaneous bulges perceived in kitsune-tsuki? In both Western and Eastern diagnosis, female mental illness is a question of weakness, of lack of control – an inability to restrain emotions or sexual urges that manifests in the contortions of the body. That hysteria is understood to be a performance by women for men is emphasized by the fact that they (the doctors, the men) set up so many cameras to capture it. Kiyo, photographed by the young student with his ‘very modern English camera’ is described as ‘a photographic godsend’; Charcot’s hospital includes a photographic studio. (An ambiguous cypher for modernity, the camera. Let’s not forget that Honoré Balzac, assiduous documentarian of the daily, refused to have his picture taken for fear that it would steal his soul.)

Dr Shimamura’s body, never quite his own, is failing. And perhaps, in his old age, he has grown wise enough to understand that he controls nothing in his house, where the women hide objects and papers under floorboards, literalizing a Freudian model of the unspoken and repressed. Resolution comes in the only way possible, both expected and inexplicable. The Japanese have a saying for strange phenomena, such as sudden rain on a sunny day. They call it kitsune no yomeiri: a fox getting married.

1 Jason Ananda Josephson, The Invention of Religion in Japan, 2012, University of Chicago Press, p. 185

Main image: Utagawa Kuniyoshi, c.1843-5, woodblock print. Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons