Moyra Davey and Kate Zambreno on Writing As If You Were Dead

The authors discuss diary-keeping, photography and motherhood

The authors discuss diary-keeping, photography and motherhood

Moyra Davey: Drifts [2020] is your most voluptuous and sensuous work to date, even though much of the novel is about struggle and feeling at a miserable impasse with the book you are writing. You manage to both write the problem and, simultaneously, provide the solution. You talk about block, but the writing feels like its opposite: flow. You invoke ‘the [new] texture of boredom’, ‘the energy of the internet, its distracted nature’ and wonder how to invest the writing with these particular drives, how to ‘replicate the mind wandering’. You name the affect you crave for your novel and, immediately, the writing serves it up. You have found the perfect form: a novel made up of fragments, using the note-taking practice you find so vital.

I know from the conversations between you and your friends in Drifts that, like me, you prize your relationships with writer-friends, the (usually women) interlocutors who prod us, open doors and offer sympathetic guidance, often with lightning speed. ‘Try to be with flowers,’ the poet Bhanu Kapil says to you in Drifts; later, in an exchange with the writer Sofia Samatar, you talk about ‘empty[ing] a text in order to fill it’. This speaks to a particular difficulty I’m having with a shapeless, bloated text, about which I’ve come to feel phobic. I wondered if you could expand on that particular point: the emptying out that might lead to structure.

Kate Zambreno: There’s something monstrous to the shapeless. I have a fear of it as well. I like to think of writer’s block, the dread of it, as resulting from too much material – too many notebooks filled up. For the period I dramatize in Drifts, it was also about the desire for my work to feel private and ongoing – rather than being instantly published and commodified – to be read only by my correspondents, my addressees, entirely women and non-binary writers.

In the book, one of the characters, Anna, says to the narrator that the notes are the work. I tend to gravitate towards writing that is about process – yours, Kapil’s, Samatar’s, Hervé Guibert’s and W.G. Sebald’s. I don’t think about structure, per se, or story, but I am interested in narrative and form and repetition. There’s such an organic flow to the form of your books Les Goddesses/Hemlock Forest [2017] and Burn the Diaries [2014] – the titles, the places, the sense of travelling through – that every writer who reads them begins to mimic it. These books read like they were written in the time they were conceived and are about time. When my writing feels shapeless and bloated, like it does now, malingering for years around the study of Guibert I have been working on, which was supposed to be a short text, I realize that writing is time, and must take the time it needs.

I’ve always been drawn to the suspense in Thomas Bernhard, Sophie Calle, Guibert and Sebald. Their works are note-like and documentary, but also read like detective stories. There’s an atmospheric moodiness or tension, also something that’s withheld from us throughout. In The Compassion Protocol [1995], Guibert’s narrator says – I’m paraphrasing here – that he most feels like he’s writing fiction when he’s writing in a diary. There’s a noir or speculative quality to Drifts – the sense of a coded reality that the narrator is trying to figure out.

MD: The last line of Drifts mentions beauty – not knowing what beauty is, but that it ‘adheres to many things’. I wondered how you would end this book, as it builds towards an almost unbearable tension: your fear of not being able to finish it, mounting material anxieties, your pregnant body about to explode. The pressure seems almost uncontainable. And then there is a pause, a muting and you re-emerge using the beautiful device of simply noting a date, 7 December, to mark the event of your daughter’s birth. It is the opposite of Maggie Nelson’s choice to narrate the minutiae of giving birth in The Argonauts [2015], but your laconic version is extraordinary in its own way, communicating something momentous with a rare economy of means. It shifts from the compulsive, yet no less compelling, uploading of life that characterizes most of the book. Drifts gives the fantastic impression of living and writing life simultaneously, and of doing it without shame, or perhaps doing it in such a way that shame becomes beautiful.

KZ: Originally, the ending included more of the duration and exhaustion of my labour; I was in prodromal labour for almost a month. I had already written about this fugue state in Appendix Project [2019], and I always imagined I’d pick it up again in Ghosts, the as-yet-unwritten novel that’s supposed to be its sequel. ‘Vertigo’ – the second half of Drifts – is elliptical and fragmentary; less an exhaustive recitation of the facts of a life and more about the claustrophobic intimacy of it. It was important to me that the book didn’t show a journey of motherhood; I didn’t want a baby to solve the main protagonist’s existential crisis, which is a crisis of the book she is trying to write. It was Samatar who told me that too much of the baby – even the joy of her – overdetermined the book. In a way, it goes against what some readers might want. Also, I am resistant to the ways a birth story is often told as a coherent narrative. Trauma is more fragmented, remembered later, in glimpses.

MD: The few details you give us wholly convey this bewildered state, but you make the experience completely your own. Your tender, yet slightly detached, observations of the baby and the hilarious depiction of the postpartum, scatological scene of retention/expulsion are consistent with all the earlier, non-maternal writing in Drifts. I’ve read quite a bit of the literature of motherhood and your voice is like no other I’ve encountered.

KZ: I want to hear more about writing and shame, its relationship to beauty, as it’s something I think about a lot. I wonder if it’s why we are both so drawn to Guibert, Kapil and David Wojnarowicz. There’s this moment at the end of Drifts where I cite you, trying to reference a work of yours, Dr. Y., Dr. Y. [2014], in which you are naked and pregnant in bed with your dog. A line from Anne Sexton’s Words for Dr. Y. [1978] frames the central image: ‘Why else keep a journal, if not to examine your own filth?’ So much of your work, both the videos and the writing, engages with the diary or notebook – the intimate space of the domestic. But there’s also an intriguing opacity in your work that I identify with, in tension, perhaps, with this beautiful transparency of the daily: the refusal to go back to trauma or childhood, that space of memoir you refer to as ‘the wet’ in Les Goddesses/Hemlock Forest.

MD: Shame is only ugly when it’s hidden. It can be breathtakingly beautiful when a writer puts it out there without fanfare. I’m quite preoccupied with shame, so I home in on authors who’ve found ways to write it. That’s what good literature does: in the right hands, shame doesn’t even exist because it becomes something else. I think it was Nadine Gordimer who said: ‘Write as if you were dead.’ This is something I try to do, but I am not there yet. The artwork with my dog and me in bed is surrounded by little photos of her shitting. I thought the curve of her arched back mimicked my pregnant belly; I was no doubt projecting onto her defecation a wish to empty myself out. The unofficial title for that piece was Ante-Partum Document. I showed it to my gallerist at the time, Colin de Land, and he recoiled from it, compared it to the worst of ‘feminist art’. I don’t hold any of this against him, but I was ashamed and put the piece away. I have Gregg Bordowitz to thank for encouraging me to revisit it nearly 20 years later and remake it using the Sexton quote. I was reading Sexton for another project, the video Notes on Blue [2015], and came across that line in Words for Dr. Y., which is dedicated to her analyst. Entirely coincidentally, Dr. Y. was the name I gave my shrink in the video Fifty Minutes [2006], so I titled the new piece Dr. Y., Dr. Y.

KZ: So much of your art seems to be about ‘The Problem of Reading’, to quote the title of a 2003 work of yours.

MD: There are many problems of reading. There is the research problem – trying to put your hand on the right thing, and often not knowing what that is. I met a graduate student in Toronto, named Kate Whiteway, who used the expression: ‘Being in the Eros of research.’ My oldest friend, the writer and translator Alison Strayer, spoke of that zone of reading as a state of bliss, when there’s never a question, where one thing leads to another. But, for me, there is also the problem of being over-identified with reading, and so I am trying to change it up. In my latest work-in-progress, I originally decided there would be no citations, but then I felt utterly compelled to write about Hilton Als, Carson McCullers and Christa Wolf. I don’t know that I’ll ever write something that is not dependent on communion and connection.

KZ: I also feel I’m often over-identified with reading. It seems people sometimes read my work to get a bibliography out of it. Which is perverse because I frequently go through periods of extreme reading allergy. So much of Drifts involves searching for books to read but finding everything too porous. It’s a relief when I am reading ecstatically, when I have the time and space. Especially when I’m pregnant – I’m again in my second trimester – I can’t read much. I spend a lot of time looking and thinking and feeling, and then eating and sleeping. I become like my dog. Which reminds me of that moment in Burn the Diaries, where you describe Eileen Myles’s passage about her dog, Rosie, shitting and you feeling a kinship looking at your own dog, Bella. I felt such an uncanny affinity reading that passage, because so much of my notetaking was observing dailiness. I’m inspired by the way your mind makes connections over texts. Much of Drifts came from walking around my neighbourhood and the city, desiring to take series of photographs, whether of my dog on the porch or the bark of the trees or the feral cats or Halloween decorations. Throughout, I was thinking about images, like the 16th-century prints of Albrecht Dürer, Peter Hujar’s photographs of animals [1960s–’80s], Sarah Charlesworth’s ‘Stills’ [1980]. The book includes not only some of my amateur photographs but also collages and diptychs. I admire how you use and philosophize photography, including your own, in your writing. Was your writing practice always concurrent with your image-making practice?

MD: For a long time, I only made photographs, and dabbled in the moving image. I didn’t really start to write until after editing Mother Reader [2001], at which point I wanted to take a break from photography and focus on writing and video. My most recent photographs are black and white images of chickens, horses and dogs taken with my late-1960s Hasselblad. The series was spawned partly by a recent film project and partly by a desire to actively channel Hujar’s animal portraits. That was a humbling learning experience. It’s uncanny how we have overlapping spheres of influence and projective desire for certain artists and writers, even down to the title of your forthcoming book on Guibert, To Write as if Already Dead. I love hearing that the impulse to write Drifts was so strongly linked to your photographic dérive. Maybe that is the answer to my bloated, stalled text: to reconnect again with images, as filtered through writing.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 212.

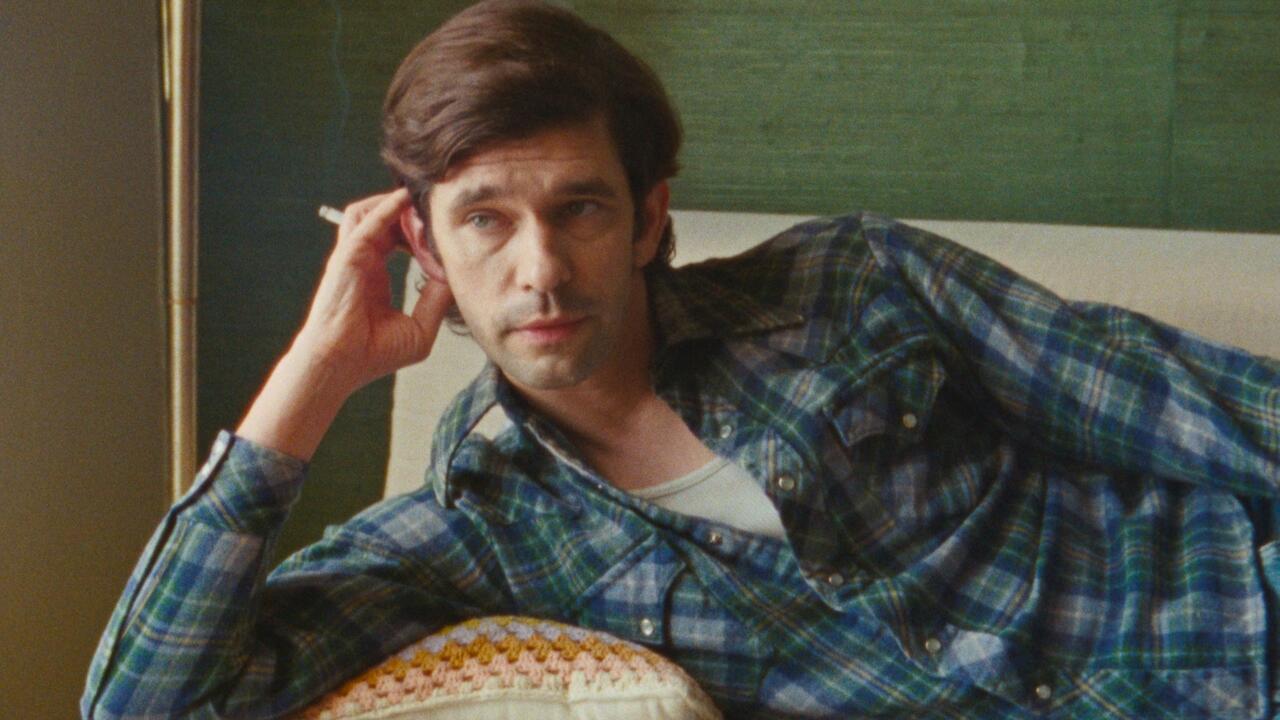

Main image: Moyra Davey, Jane (detail), 1984, gelatin silver print, 51 × 41 cm. Courtesy: the artist, greengrassi, London, and Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne/New York