Painting the End of the World

Natasha Stagg on the work of Chris Dorland

Natasha Stagg on the work of Chris Dorland

I’ve been friends with the artist Chris Dorland for years, but it’s one of those friendships that usually needs an event or project – a gallery opening, a party, an article – to prompt one-on-one conversation. When we do talk, it’s often about the future – of publishing, politics, art, anything. And so, as science-fictional-sounding terms like ‘Operation Warp Speed’, ‘the Capitol insurrection’ and ‘GameStop short squeeze’ made it into US vernacular, I was glad to have an excuse to catch up with Dorland during the socially distanced winter of 2020, when he was working on his recent solo show, ‘New Day’, at Lyles & King in New York.

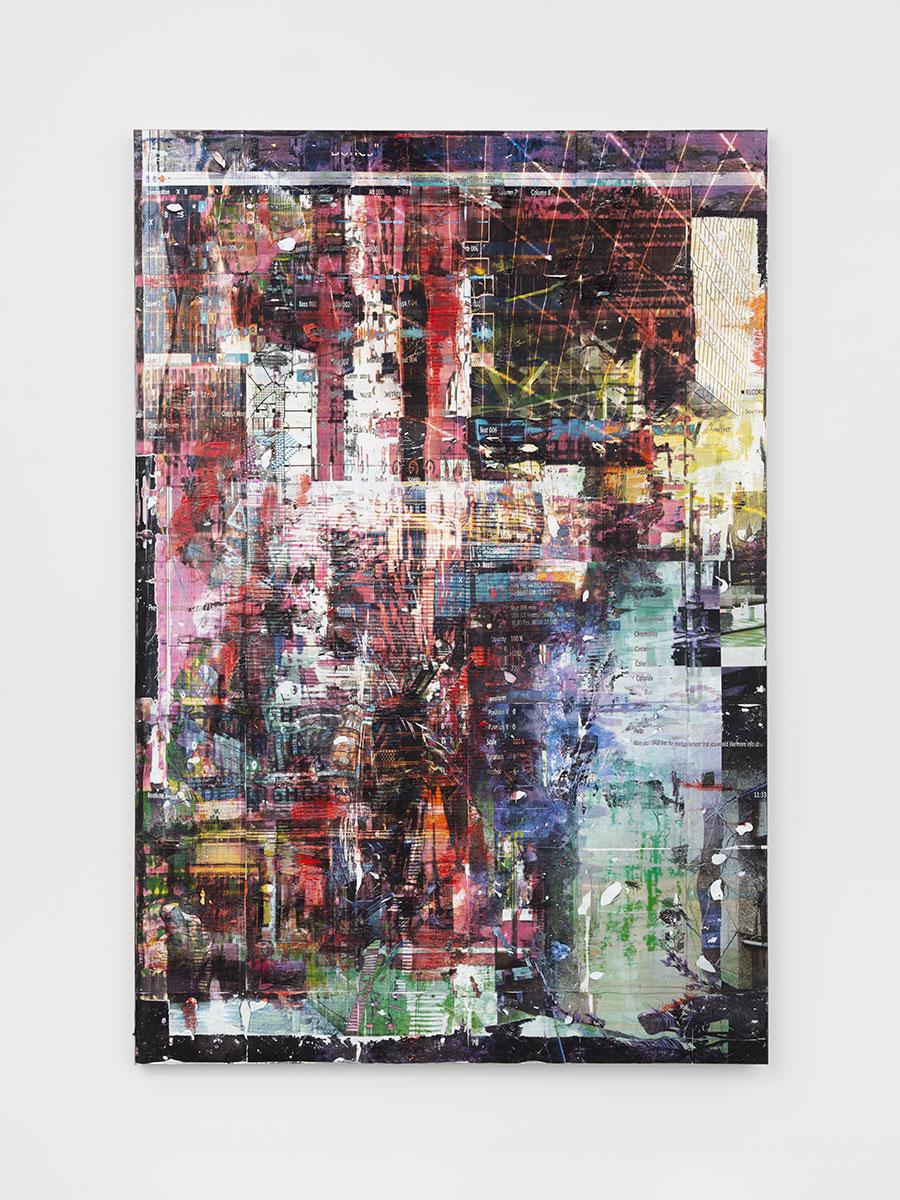

First, I wanted to know if Dorland feels a vague sense of déjà vu lately, as if all of this were projected by some fantastic dream. ‘We are living in a science-fiction future nightmare dreamt up 30 years ago,’ he agrees. ‘You should totally play Cyberpunk 2077,’ he adds, citing it as ‘the most highly anticipated video game ever’. Although Dorland’s not a gamer, this suggestion doesn’t surprise me. The ads for Cyberpunk 2077, which I’ve seen on bus stops and billboards around a boarded-up Manhattan, are in the same headspace as his multimedia paintings, which often create uncanny collages of modern emblems and cyberpunk tropes. For example, in some of Dorland’s newest works, computer desktops appear within an acid neo-noir colour scheme, collapsing soon-to-be dated graphics and past renditions of a fictional future.

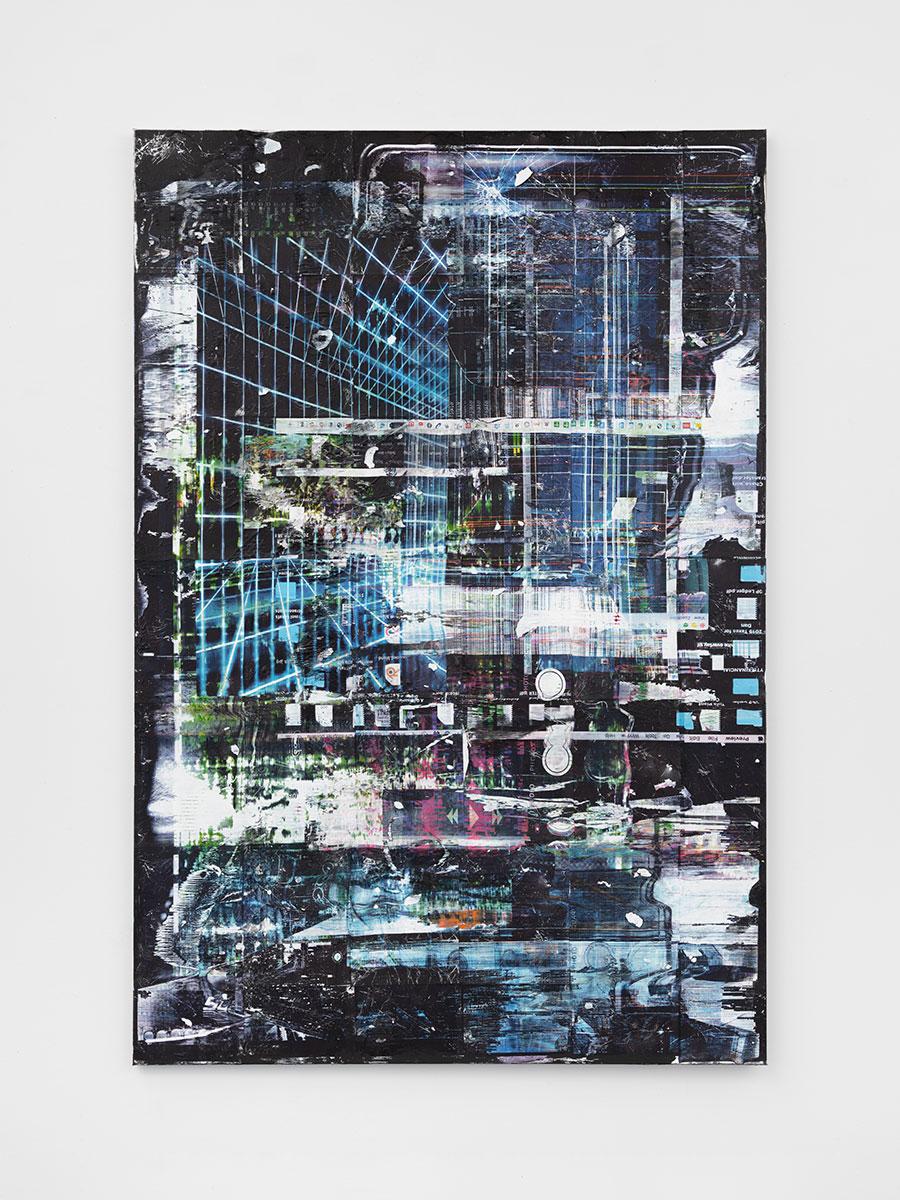

‘New Day’ consists of eight paintings on linen and two looping animations. The paintings are made digitally and printed in layers of acrylic, ink, gesso and UV resin, giving a rugged, earthy texture to elements typically found on screens. With titles like Untitled (breach), Untitled (instinct mode) and Untitled (bleeding edge) (unless otherwise stated, all works 2020), they occupy a charged middle ground between the seemingly organic and the mechanical. Magentas, cyans, greens and fluorescent whites are created using a combination of underpainting and image transfer, a technique that helps them glow like computer pixels. Digital lines fuzz, as if seen through watery eyes. Shattered glass appears naturalistic, spider web-like. Rainbow hues burst from glitch-like patterns. A canvas resembles a darkened screen that reveals its user’s reflection. ‘Honestly, I was so happy to be working with my hands,’ Dorland says, ‘in what felt like a world that was teetering on the edge of the unknown.’ His studio is in New Jersey, and having a reason to take public transit during the COVID-19 pandemic became ‘exhilarating’, even inspiring, if also unnerving. ‘I was literally the only person on the PATH train from Manhattan to Jersey for months,’ he adds. ‘It was incredibly apocalyptic, and I loved it.’

The world outside our windows has looked like a few versions of ‘apocalyptic’ of late: makeshift hospital tents and autonomous zones; abandoned centres of culture and commerce; surveillance vigilantes holding flags for cult ideologies. None of this has happened before, but the déjà-vu sensation comes from recognizing narratives that inform today’s scenery. The most apt way I can find to describe the experience of seeing a cop car explode into flames as I turned a corner in SoHo last summer is ‘straight out of a movie’. Taking Dorland’s advice, I watched They Live (1988), Akira (1988), Hardware (1990) and Strange Days (1995), newly dazzled by these plots of hyperconnectivity that put so much emphasis on the tactile. In the genre of cyberpunk – which Bruce Bethke christened in a 1983 short story, though its origins can be traced to the 1960s – broken communities and ecological catastrophe act as counterexamples to the dreamscapes of mainstream science fiction. Cyberpunk’s literature, cinema and games depict societal breakdowns as opposed to well-oiled machines, automatons dulled by humanity as opposed to ultra-sleek robots.

Cyberpunk worlds also tend to take place in a more extreme version of the present, rather than a wildy speculative distant future. Here, the media manipulates viewers’ bodies (Videodrome, 1983), humans are made into cyborgs and vice-versa (Robocop, 1987, and Bladerunner, 1982), corporations and governments plant false memories into game-ified brains (Total Recall, 1990, and eXistenZ, 1999). As technology advances, the genre argues, the average quality of life deteriorates. In these films, cybernetic body horror serves as metaphor for the blur between our lived experience and corporate agendas. Gore was often the best option when the software necessary to produce concepts like deep fakes and augmented reality was unimaginable.

This is a friction that interests Dorland: that messier, more bodily aesthetic used to describe the inner conflict caused by major technological leaps, like AI. In Untitled (species) (2021), a semi-transparent cephalopod pulses with intricate patterns, a cross between digital metadata and bioluminescent emmissions. This and the other animations in ‘New Day’ were each created using a generative adversarial network, which Dorland describes as ‘a form of machine learning in the same family as deep fakes’. The effect is at once mechanical and organic, reminiscent of the living quality found in spaces devoted to electric advertisement – like Times Square in New York – even when devoid of people.

First launched in 1988, the pen-and-paper role-playing game that formed the basis for Cyberpunk 2077 was set in 2013, 2020 and 2045. The game is narrated by Keanu Reeves, who bridges many cyberpunk spheres by starring in all four films of The Matrix franchise (1999–ongoing) and the 1995 film adaptation of William Gibson’s Johnny Mnemonic (1981). After almost a decade of false starts, Cyberpunk 2077 was finally released last December – only to be pulled seven days later by Sony, due to customer complaints. This was just another glitch in a year that already felt, to many, pretty Matrix-like. Players of Cyberpunk 2077, hoping to enter a virtual cyberpunk landscape – during an actual government-issued quarantine, drones circling overhead, while percolating conspiracies undermined the credibility of traditional media – were largely unsatisfied that the game didn’t accurately depict a made-up post-apocalypse due to a list of unsettling bugs. The irony was not lost on Dorland, who dove into the game’s contemporized retro-cynicism. The situation, I tell him as I sit in an apartment I haven’t left in days, reminds me of a constant stream of complaints concerning the way the present looks, no matter how closely it resembles the one we were promised by sci-fi stories: where are the flying cars and jetpacks?

‘I feel like the future is fully here,’ Dorland says, echoing the famous William Gibson quote from a 1993 episode of National Public Radio’s ‘Fresh Air’: ‘The future is already here, it’s just not very evenly distributed.’ He lists similarities between conditions outlined by some of his favourite plots and our current climate. ‘Little pocket devices we are glued to constantly that allow global interconnectivity, 24/7 shopping and access to the world’s largest and most complex database; a world literally being ravaged by the spread of a fast-moving disease; 20th-century postwar alliances falling apart; an impending climate catastrophe getting more intense every year; a reckless, reality-show [former] US president; James Bond villain-like strong men running rogue states; increasing distrust of reality/authority at the civilian level; surveillance mechanisms at a scale the likes of which has never been seen in our history; untold concentrations of wealth and power lying with the very, very few; growing racial discord; alarming and repetitive state-sponsored hacking; politics as entertainment ... and that’s just the tip of the iceberg.’

According to some cyberpunk lore, set out in Johnny Mnemonic, ‘the second decade of the 21st century’ is when ‘corporations rule [and] the world is threatened by a new plague’. ‘New Day’ is a reprieve from the screens to which we’ve all become yet-more glued in the 2020s, even if it is inspired by them. It depicts earlier visions of the future using the symbols and technology of today and, in this way, lives sublimely in the moment. It recalls movies the artist watched and re-watched as a kid, imagining a life in one of these emptied-out megacities. Soon, these movies told him, a digital world – as inhabited as the physical world, if not more so – would be haunted by creeps, fought over by businesses and defended by hackers. Outsiders would rely on the corrupt systems that had taken over, while appreciating the realms in which they fell short. The fate of humanity would be in their hands. Heroes would be present, not plugged in, hyper-aware of each arena they straddled. The references to these fantasy plots feel apropos, after seeing so many modes of protest online and on otherwise vacant streets.

Gibson said in a 2014 interview with Laura McClure for TED that his stories were never meant to predict the future, but to ‘get a handle on the present, the present having become extremely fantastic’. The cyberpunk tropes that lace Dorland’s still and moving collages of present-day banalities – app icons, Wikipedia-page text, skin-like wrinkles – follow this directive, expressing interest in the hyper-now. The future is here, and it is nostalgic for the past that imagined it. It is scary, appalling and chaotic, but also familiar, since it is somewhat based on cinematic projections. And, in that way, it is, at times, quite beautiful.

Main image: Chris Dorland, Untitled (species), 2020, film still. Courtesy: the artist, Lyles & King, New York, Super Dakota, Brussels, and Nicoletti Contemporary, London