One Diagram To Mind Them All: Hyperspace in the 1970s

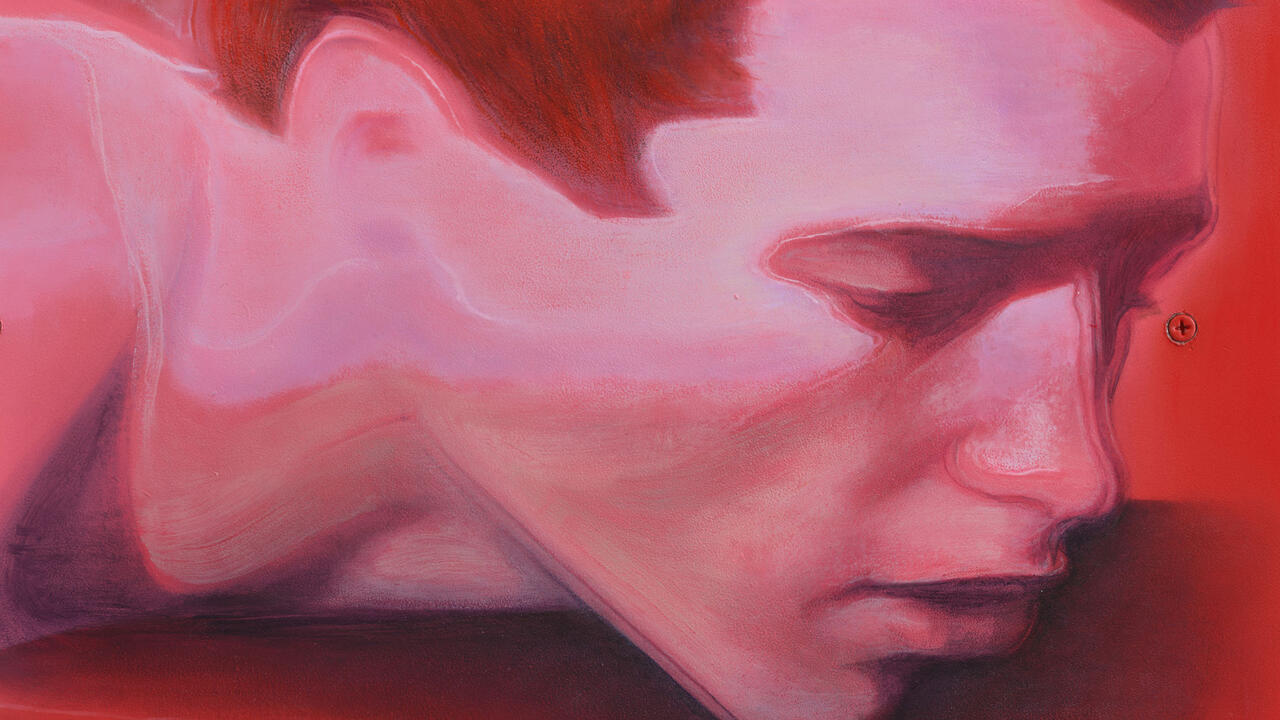

Tony Buzan’s early hypertext system for paper

Tony Buzan’s early hypertext system for paper

Earlier this year on 13 April, Tony Buzan, the inventor of the Mind Map, a world famous visual device for organizing thought and developing ideas, died at 76. Mind Maps are nearing a half century of international use in schools and businesses, they are cited as a study aid by BBC Bitesize and are a ubiquitous brainstorming technique. If brainstorming itself had a logo, it would probably be the Mind Map. Writers might draw a mind map before beginning to write an article like this one. And contemporary artists, the likes of Thomas Hirschorn, Jeremy Deller and Ian Cheng, have riffed on the form. Mind Mapping has become omnipresent, but its inventor and his original zestful vision are often eclipsed.

A student of Psychology, English and Creative Thinking, Buzan first rose to prominence in the 1970s with the publication of a book about speed reading and a ten-part television series produced by the BBC, Use Your Head (1974), which promoted mental literacy in the same fashion that John Berger’s Ways of Seeing (1972) promoted visual literacy. In Use Your Head, Buzan screened excerpts of art films like Charles & Ray Eames’s 1968 Rough Sketch (the precursor to Powers of Ten, 1977) alongside original cartoons such as Pattern Man vs. Linear Man, doodled on camera, played with teddy bears and requested the audience to participate in memory games. Buzan was also a close friend of British Poet Laureate, Ted Hughes, for whom he wrote his own poem, Requiem for Ted (2006) - which he reads in his2012 TEDxSquareMile talk.

The most popular practice of mind mapping today uses a diluted ersatz of Buzan’s colourful and poetic graphic system. A frequently drawn mind map, usually a rough sketch in ballpoint pen, overlooks the inventor’s attention to vibrant visual expression. As boring as these tend to be, many still find them beneficial. Buzan spent much of his career selling the idea to big business, so it’s no surprise that the internet is full of spammy marketing pages, half-baked software products and mundane conference presentation videos on the topic.

An authentic Buzanian Mind Map begins with an exciting central image: ‘Instead of [using] the word eye, we can do a little sketch’, he insists as he places a photograph of himself in the centre of another. The image then radiates hierarchical, ever thinning tree branches of colour, independently labeled by key words or symbols. At any point, a symbol on one map may be appropriated and used as a central image for a new map, forming a graphic ‘re-presentation’ (Buzan’s emphasis) of an inner mental network. He asks Mind Mappers to draw organic shapes and advises against the use of borders: ‘Boxes are like little prisons, which your thoughts are trapped in… don’t use boxes.’ He espouses formal variation – in hue, shape, texture and size – through a homespun theory, informed by his observations of children, that the full activation of senses increases mental capability. Much of his rhetoric echoes the tenets of formal modernist painting and early conceptual art: Buzan was like a fine art professor to the business world.

In a corporate 1970s world overrun by typewriters and monochrome documents, Buzan was evangelical about nonlinear thinking in dynamic pictures. As his system paled and was assimilated by the mainstream, he continued to preach the spirit of the Mind Map to his audiences. His informational approach predates the Web by about two decades, but it closely resembles hypertext in its structure. The inventor of hypertext, Ted Nelson, published his treatise on the nonlinear capabilities of the computer, Computer Lib / Dream Machines in 1974, the same year that Use Your Head aired on the BBC. The critic and teacher Howard Rheingold, who created Whole Earth Lectronic Link (WELL), one of the first social networks, refers to Mind Maps in his syllabi, while Mark Zuckerberg cites WELL as an inspiration for Facebook. And Facebook places each user, as an ‘exciting central image’, at the centre of their personal 'social graph' or mind map.