Patrick Nickell

Luckman Gallery, California, USA

Luckman Gallery, California, USA

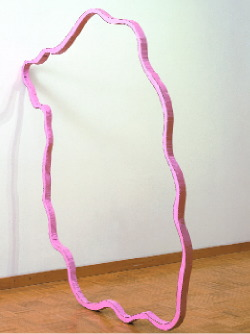

For the past 15 years Patrick Nickell has been making messy, minimal sculptures from found and discarded materials such as cardboard, twine, plywood and scrap metal. In his first survey show, featuring 37 sculptural works, his creations offer up nothing more philosophical than the conundrum of 'stuff' - where to put it and how to transform it effectively into a range of interesting objects. What he comes up with is a body of work that is casually rigorous but insistently fussy. Poolside (1999), for instance, is a precariously balanced doodle in space, painted a bikini pink. Because of its colour and name it has a funky, if forlorn, quality, like a misshapen hula hoop left by the kerb.

Abstract, whimsically inclined sculpture is nothing new. The Modernist precedent, of course, is the work of Jean Arp, Alexander Calder and Joan Miró, whose saturated colours and shapely shapes were absurd but painstaking and, although highly stylized, sometimes referenced the body.

A little bit closer to home are Richard Tuttle, Liz Larner and Tim Hawkinson, whose constructions rarely, if ever, connote the body. Nickell's work is clunky-chic Pop Minimalism, but his nod to Modernism - conscious or not - is his intense focus on single-object sculptures, rather than installations or multi-part objects. Each piece, no matter how small, is a work unto itself. These days, in the age of über-installation, that is refreshing. There are no series, no numbers and few, if any, titles - and the ones that do exist aren't particularly witty. And there are certainly no 'untitled' works that add a second title in parentheses.

Rather, the focus of Nickell's work is physical articulation. What he excels at is turning a two-dimensional scrawl into a three-dimensional sculpture. A cascade of circles, tangled squiggles, rough-hewn flowers and a large yellow asterisk all resemble a sort of absent-minded doodle. Making marginal shapes from marginal materials, he conveys the integrity of building. There is something very architectural about his pursuit, assembling bits of detritus to form something solid and lasting. Like Tom Friedman or Thomas Hirsch horn, Nickell enthusiastically brandishes ugly materials, but has a greater concern for beauty than wit. Admittedly there is a 'boy art' quality to the work - gruff, unassuming, semi-literate. Most of Nickell's work was produced during the 1990s, a decade when the body was the subject of intense scrutiny and representation.

At that time there was a great tendency for sculptors to focus their materiality in the direction of the bodily, often through obvious means: hair, wax, bits of cloth or other soft, porous materials. Not Nickell. His works may be quirky, but they are decisively formal, choosing clean idiosyncratic lines any day over fleshy curvaceousness. Affably scruffy, perhaps Nickell's work is so compelling because it is insistently, even obstinately, elegant. This is seen in his adept use of light - creating cut-outs, porous plastic and open spaces through which light will pass to create evocative shadows on the walls behind and beneath the works. Shadows add a dramatic flair that insists on his sculpture as more severe than comic. Were Nickell's materials not so humble, his sculptures might be pretentious. Instead, they are gracefully, gloriously mundane.