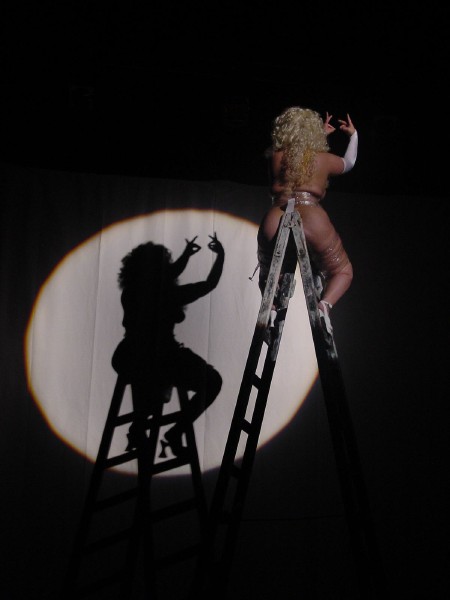

Art/=Vida

Museo del Barrio, New York, USA

Museo del Barrio, New York, USA

© FRIEZE 2025 Cookie Settings | Do Not Sell My Personal Information