Pavement to penthouse

The aesthetics of folk

The aesthetics of folk

There's no denying the current popularity of Folk music. The success of the soundtrack for the Coen brothers' film Oh Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000) has undoubtedly sparked off a revival in the fortunes of American Folk, and a quick glance at mags such as fRoots or Dirty Linen reveals that in Britain alone there are dozens of festivals taking place up and down the country: Chippenham, Accrington, Derby, Ludlow, Cleethorpes, Sidmouth, Durham, Lincoln, Cambridge and Fairport Convention's own annual bash, Cropredy. But whether all this represents a healthy backlash against the loud manufactured beast of Techno Pop or simply a trip down memory lane is hard to tell.

Folk music has been around since time immemorial and can justifiably claim to be the forerunner of Country, Jazz, Blues, Rock and the various hybrid forms derived from them, to be the source from which nearly all other popular music is drawn. It was, after all, the first music to explore personal and environmental relationships by telling stories about religion, life, politics, love and war. These were passed down from generation to generation, and troubadours spread gossip and news from village to village. (The first victim at the Battle of Hastings in1066 was a favourite minstrel to William the Conqueror called Taillefer; a Norman manuscript still exists praising his craft.)

Folk even managed to traverse continents. The Pilgrim Fathers who set sail across the Atlantic in 1620 took with them hymns and spiritual songs, and the sailors their jigs and shanties. Black slaves from Africa also took their Folk music to America, where it became the Blues. 'Amazing Grace', sung by the opera singer Renee Fleming at Ground Zero in the wake of 11 September, was actually written in 1760 by John Newton, vicar of St Mary's Woolnoth, London, before making its way to America. By the 1930s American Folk music had become urban as well as rural. Stories of steel mills, railroads, prison gangs, coalmines, city life and poverty became the staple fare of singers such as Woody Guthrie or Huddie Ledbetter. And it was powerful stuff: these first real voices of social protest were seldom heard on light entertainment radio.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s Britain was building its own movement for peace and social justice, complete with campaign songs. Protest marches organized by CND provided the stimulus for Folk writers such as Peggy Seeger and Ewan MacColl, who penned 'The Bomb Has Got to Go', featured on the LP Songs against the Bomb (1960). The typewritten sleeve notes inform us that 'In the heart of Soho the Ballads and Blues Association holds its Hootenanies weekly, providing an opportunity for people to sing and listen to Folk songs before convening to the Partisan Coffee House.' But relations between CND and the folkies were not always so harmonious. The first CND rally of 1958 was supposed to be held in silence, but when the marchers arrived at Trafalgar Square a Folk group called the City Ramblers shattered the organizers' dreams with a rousing rendition of 'Ain't Gonna Study War No More'.

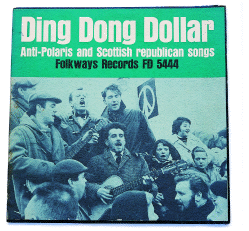

The cover of the Ding Dong Dollar album, issued by Folkways in 1962, is a brilliant piece of graphic design; the green photograph places the demonstrators in a historical and social context. These are peaceniks with beards and bow ties, but duffle-coats are obviously also de rigueur. The Cold War generation may have been told they had 'never had it so good', but they were genuinely scared of an all-out nuclear attack. After all, it was only 17 years since atomic bombs had wiped out Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Album cover design around this time was essentially a cottage industry, especially in Folk, where budgets were limited and distribution was small. Most record covers had a functional simplicity, giving basic information rather than offering elaborate designs, but there was a spirit of youthful exuberance bursting to get out, not to mention the 'Ban the Bomb' badge of honour. The simple black and white emblem was the Mercedes of cool and no right-minded art school student would be seen without one. It became the universal calling card of anarchy in the 1960s and represented a serious threat to authority.

On both sides of the Atlantic the late 1950s and early 1960s saw a proliferation of Folk purists who preferred to perform songs that often dated back several hundred years. Robin Hall and Jimmie MacGregor (who took part in the 1958 Trafalgar Square incident) and America's Doc Watson were typical Folk/Blues artists steeped in traditional music. Their album covers use bold graphics and a black and white photograph of the artists in a 'smart yet casual pose, with guitar'. The image lends a solemnity to the artwork and suggests that the music inside should be taken seriously - and it was.

It is difficult to say whether black and white photography was used deliberately to create a downbeat, moody look or whether it was just a matter of expense. Colour television was still unknown at this period, and magazines of the period used colour on the outside and black and white for their inside spreads. At the cutting edge of graphic design were Jazz labels such as Blue Note, which always used monochrome photos with cool indigo graphics and zany typefaces. This influence probably spread to Folk via the Beat movement, which mediated between the bohemian world of Jazz and the hobo lifestyles of Folk music. After all, Woody Guthrie had sung about riding boxcars as a young man, and bumming around was becoming fashionable.

In the mainstream music biz of the early 1960s most album covers still used a portrait of the star, heavily retouched and glamorized, to appeal to a clean-cut American youth. Bobby-soxers were just out of school, and the old 1957 Chevrolet was being traded in for the new-style, space-age Impala. Elvis had just been released from the army, and long hair was still a long way short of acceptance. But in times of change Folk music had always bucked the system first, and The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan was no exception. Released in May 1963, the cover showed Bob Dylan and Suzie Rotolo, clearly in love, walking down snowy Jones Street, New York, photographed by CBS staff photographer Don Hunstein.

Rotolo had met Dylan when she was just 17. She came from an artistic, left-wing family: her mother supported trade unions and campaigned for racial equality. Dylan, broke and relatively unknown, spent time at the Rotolo home on 1 Sheridan Street and picked up a lot from Suzie. They read poetry together and, most importantly of all, she introduced him (through her mother) to the protest movement. She even persuaded him to perform at a benefit for the Congress of Racial Equality in February 1962. As she said herself, 'It was all music, poetry, and politics rolled into love.' Rotolo encouraged Dylan to write protest songs and when Freewheelin' finally came out after some twelve months in the making, it had some of his finest work, including such classics as 'Blowin' in the Wind', 'A Hard Rain's Gonna Fall' and 'Masters of War'. Rotolo found the success of Freewheelin' - and the fame it brought her lover - difficult to deal with, and the relationship faded. In any case, Dylan's libido had wandered elsewhere, and in a shrewd and probably calculated move he found romance with the already established Joan Baez.

One of Dylan's early influences on the 1960s Folk scene was Dave van Ronk. A great bear of a man, with a deep, gravelly voice to match, he was five years older than Dylan and by the time they met he was already well known in the local Folk clubs and had made some fine recordings. He allowed the 19-year-old Dylan to crash on his sofa and became his mentor, teaching him literature, politics and how to pick a mean guitar; on his début album Dylan recorded van Ronk's arrangement of 'The House of the Rising Sun'. But also credited on that album is Eric von Schmidt, who is given as the source for the song 'Baby Let Me Follow You Down'. Von Schmidt was a popular Boston Blues singer/guitarist and painter who discovered that he could make a living from his artwork as easily as from playing the guitar. In 1961 van Ronk had von Schmidt paint a portrait for his album cover, Van Ronk Sings. In January 1963 von Schmidt moved to London to make an album with Dick Farina (Joan Baez' brother-in-law) and to produce the artwork for the album cover. In London he shared a house with Dylan, who put in an appearance on the album (credited as Blind Boy Grunt). Since those heady early days von Schmidt has made many of his own albums and become well known for his consistently interesting cover art, particularly in the Folk world, producing work for the likes of Baez, Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie.

Von Schmidt's unique style suited Folk perfectly. He painted caricatures, using weird shapes and colours that he felt captured the music inside. His artwork was always textured, bright and uplifting, very different from the usual posed photo, medieval brass rubbing or Victorian doll's house sort of image that usually adorned Folk albums. His pictures felt intensely personal, as though he had an intimate knowledge of his subject, which he probably did, and wanted to share it with the viewer. Records were treasured possessions in those days and it was easy to develop an attachment for a cover, either because it packaged your favourite sounds or simply because you found the artwork interesting and stimulating as you pored over it while listening to the music. Von Schmidt had that ability to draw you in.

But the most successful Folk singer of the protest movement, particularly at the time of the anti-Vietnam War, was Baez. Although she rarely wrote her own material - her recordings were nearly all traditional songs until her relationship with Dylan flourished - she still sold albums by the million. And with the money rolling in she was able to employ the most famous and expensive American photographer of the time, Richard Avedon, to take the cover portrait for her 1965 album Farewell Angelina (which contains no fewer than four Dylan songs). Avedon is even credited on the front, just above Baez' left shoulder. It is a hard, brutal and masculine picture, unlike her previous covers, which had depicted her as an ethereal, waif-like gypsy.

By the 1970s Folk art had lost much of its initial punch. Major record labels realized that there were bucks to be made from Folk music, and their influence began to dilute the movement, creating bland and commercial-looking sleeves that unfortunately mirrored the music inside them. The Settlers Alive (1970) and Turning It On (1964) by the Gaslight Singers are probably two of the most depressing examples of Folk sell-out. One looks like 'Summer Holiday' and the other like a Sta-Prest ad. But by now even Dylan had gone electric and begun to disassociate himself from protest causes.

Meanwhile in Britain Folk Rock was being born. The Incredible String Band, Pentangle, Fairport Convention and then Steeleye Span were among the most successful exponents, playing self-penned as well as traditional songs and using electric instruments. But the leading lights of the British Folk scene of the late 1960s had a sense of humour in their performance and were not as dark and intense as their American counterparts. In 1968 Pentangle decided to commission the Pop artist Peter Blake to create a cover for Sweet Child. Blake had completed the Beatles' Sergeant Pepper cover only the year before, and decided to make Pentangle's design out of glitter. Sadly the cover didn't sparkle after it was photographed and printed, but it's still a striking piece of design.

The cover of Fairport Convention's Unhalfbricking (1969) was another radical departure from what might have been expected of a Folk act, with a photograph by Eric Hayes of singer Sandy Denny's parents, Neil and Edna, looking rather uptight by their garden fence while the band sun themselves and take tea behind a low brick wall. Surreal you might say, but what does it all mean? The group apparently so upset their American label that they replaced it with an image of trampolining elephants. The cover of the Incredible String Band's 5000 Spirits (1967), meanwhile, was a trippy piece of psychedelia painted by the Dutch couple Simon and Marijke, who also designed The Fool for the Beatles' clothes shop Apple. Folk was walking hand in hand with the drug culture, and with big business. Much later, in the mid-1970s, Steeleye Span's Commoners Crown (1975) had a sculpture made out of thousands of figurines of the group in gold. As one member of the band was heard to remark afterwards, 'the bloody cover cost more than the bloody album to make.'

It was a sign of the times. With record sales at their peak, the rock 'n' roll lifestyle was beginning to take over the farm; Folk was becoming self-indulgent. Record companies had highly paid art directors and Folk musicians had heavyweight managers. Folk art began to become more sophisticated, with gatefold sleeves, elaborate packaging, expensive photographers, painters and illustrators, and with wardrobe and hair stylists in tow. The new style mistress was Joni Mitchell. No more painted gypsy wagons - if it wasn't a Merc in the parking lot, then forget it. Joni painted her own covers, had photos taken by Norman Sieff and lived a Bel Air lifestyle - a far cry from Ding Dong Dollar.

Yet Folk in the true sense of down-home, rustic, creative art is still very much alive - although it has sharpened its pencils and moved realistically on. Contemporary Folk musicians have a different style, and photography has become very much a part of the new world order of Folk art, which now seems to prefer upfront reality to Pop art and gold crowns. The CD revolution has affected cover design too, as the canvas is now so small.

In fact, the wheel has effectively turned full circle. John Prine, who in 1970 was signed as the next Bob Dylan (that didn't happen), had to wait until 1999 for recognition with In Spite of Ourselves; the album's black and white photo, by the great Elliot Erwin, shows two lovers sharing a tender moment in a 1960s registry office. The effect is nostalgically reminiscent of the atmosphere of The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan. In another return to the spirit of the grassroots Folk movement the cover of Gillian Welch's 2001 release Time (The Revelator) shows her sitting in a sleeveless cotton dress in a low-rent room with appalling upholstery, looking like an extra out of The Grapes of Wrath. Like the music, it's unpretentious, unassuming and honest.

The return to the simpler life and a revival in the fortunes of Folk is well illustrated by a young hippie singer called Vashti Bunyan. In 1970 she recorded an LP entitled Just Another Diamond Day; the record bombed but it remained in the hearts and minds of a few, and last year Mojo magazine called it one of the 'Great Lost Albums'. The artwork defines the real do-it-yourself approach, using a mixture of photography and paint. It was conceived by one of Vashti's band after they had travelled to the Hebrides by horse and cart to rent a cottage to work in. It sums up a fleeting but defining moment in Folk music history, when it was possible to mix the music, the art and the aesthetics together in a creative hubbub.

Two years ago, and after many problems in finding the original tapes, Just Another Diamond Day was re-released, once again to critical acclaim and with greater commercial success. The cover art was also discovered intact and lying in a shed, and that too was resurrected. The picture sums up a time of innocence and pastoral idyll with - as in all the best Folk tales - the animals waiting just outside the door.