Philippe Parreno and Liam Gillick

The collaborators discuss the London Underground and Parreno's commission for Tate Modern

The collaborators discuss the London Underground and Parreno's commission for Tate Modern

Liam Gillick We first met in Nice in 1990, didn’t we? I came to look at an exhibition at Air de Paris titled ‘Les Ateliers du paradise’. The invitation was intriguing: it was like a credit card, so I asked Artscribe if they would pay for me to go and review it – I was doing a lot of writing in art magazines then – and they said No. But I went anyway. London was going through this crazy hype moment around 1990, after ‘Freeze’. But I knew it couldn’t be the only place to be, the only way to think.

Philippe Parreno ‘Les Ateliers du paradise’ involved three artists: Pierre Joseph and Philippe Perrin and me – and the idea was just to be in the gallery and live there, and people would come in and discover us playing video games and reading books. An exhibition in the form of a vacation.

LG In Britain everyone then was anxious about the frame and the edge. There was a lot of irony around. But after I experienced ‘Les Ateliers ...’, the anxiety about the frame went away; there was a politics about the exhibition that was really refreshing. It was like a film in real time.

PP When we started talking together, you were also collaborating: we were negotiating our positions as artists.

LG I think you often start by asking: Why is this place designated for art? Why is this an artwork? Why is this cartoon on the TV on a Saturday morning? We were both in ‘No Man’s Time’ at the Villa Arson in 1991. You took these moments, fragments of scenes from popular culture – like the sign from Twin Peaks, or the Mogwai in the photocopier from the Gremlins movie, and used the site of the exhibition as a place to play with fragments and scenarios, value and time. I think it’s taken a long time for some people to realise what you were really doing. You’ve been showing for over 25 years, and it’s taken this long ...

PP That’s true for you too.

LG I’m a more orthodox artist. I was influenced by American writing; artists like Robert Morris and Lawrence Weiner. For me your work presents a more psychotic character, and mine’s more schizophrenic.

PP My brain is digressive. One thing leads to another. That is so true.

LG Your work often deals with new strains: synapses that connect things, but are not necessarily visible. When you made the glow-in-the-dark posters [Fade to Black, 2013] you were showing that systems are only visible when you change the state of experience. Only when you turn the lights off do you see the work. Then there are the marquees, which you return to again and again, which signal an event but don’t carry any information.

PP They’re totally meaningless objects that occupy a nice space between the floor and the ceiling, a place where you don’t usually see art. They’re OK, and then they have this potential to become something else when they are exhibited together. All together they form another object. An object made out of objects.

LG Normally a marquee tells you what’s on. Here they don’t. They signal to people that something might happen. In the show like ‘theanyspacewhatever’ [an exhibition of ten artists including Gillick and Parreno at the Guggenheim in New York 2008–9, for which Parreno installed a cinema marquee over the museum’s Fifth Avenue entrance] the marquee signals that you are ‘outside’ and you want to be viewed outside, not in a group. That there is an event taking place at this museum, but that this museum is also a part of an event as a structure in itself. The marquee lighting up on the street isolates the person at night who’s walking past, who’s standing there with their dog. People see your recent big exhibitions in big spaces and forget how anti- institutional you’ve been for your entire adult life.

People forget how anti-institutional Parreno has been all through his life.

PP I worked as a student at Le Magasin, the big art centre in Grenoble. The main space was known as La Rue [the street]. It was a large open space. My early memories of being active and thinking ‘I’m going to become an artist’ were when I was painting huge panels for Daniel Buren for the opening exhibition, or later assisting Sol LeWitt or Lawrence Weiner. Le Magasin offered large space to artists who were producing work specifically for it.

LG So you feel prepared for the Turbine Hall?

PP At the Bicocca I was working in a space with free entry, so that helped me think about the Turbine Hall. Then in New York I hung around for three or four weeks after the Armory opened. It was interesting to see how people reacted, and it allowed me to understand partly what I’m doing. I have often lived in the spaces where I was having the exhibitions. How did Buren phrase it? Live and work in context.

LG At the Armory people didn’t always know what they were seeing, and some said they didn’t know how long to spend there. That feeling of anxiety is a big effect of the work.

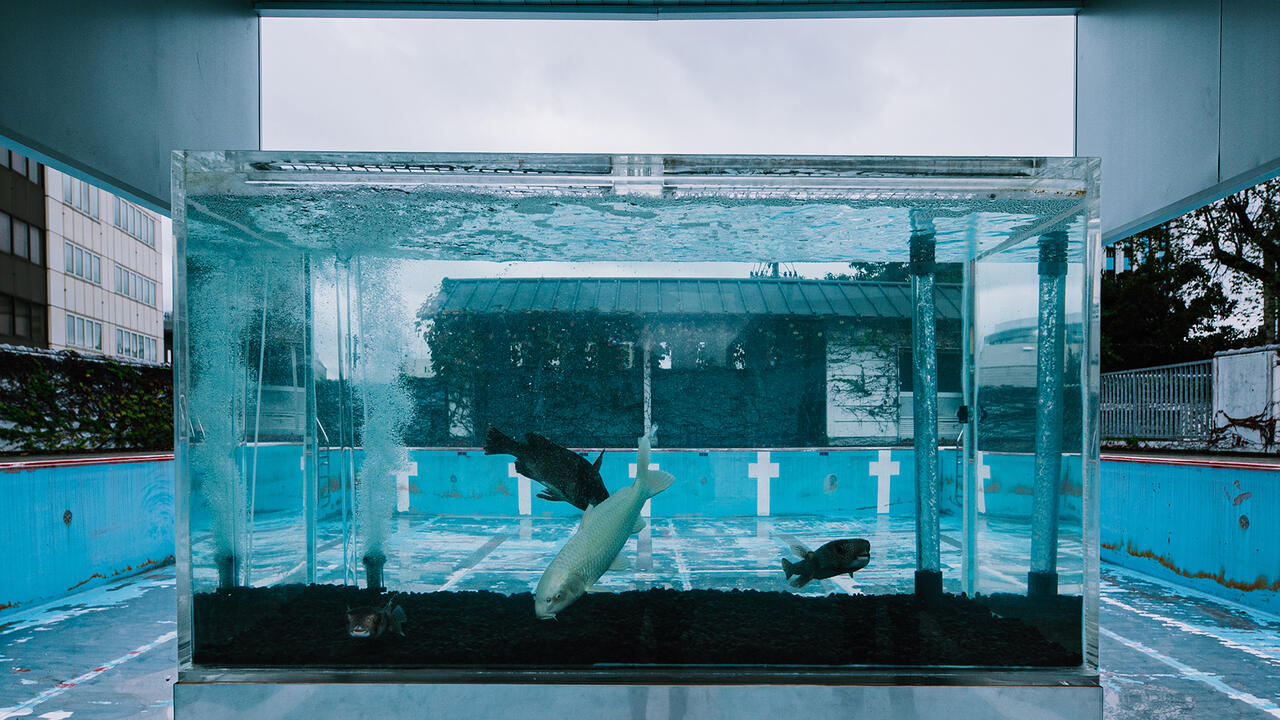

PP At Tate, I’m most aware of doing something that will last for eight hours a day. If it’s open from 10am to 6pm, the work should deal with the fact that in the morning there is daylight and at the end of the day it is dark. So that’s taken me in one direction. Another important thing is that the museum has free entry, so if you miss something, you can go back. If you go to a park in the morning it’s one experience, but if you go at night there might be an event. You will miss the event if you only walk your dog in the morning, but instead you might hear a baby cry. That durational aspect interests me. I still believe in an art-centre type of experience, where the artist takes over the space, rather than just displaying a lot of stuff.

LG I told you, the only answer is a lot of puppets and sausages. We stood there together recently looking at the space – and it’s so big.

PP I’m interested in the space itself, too, so I went to see Herzog and de Meuron in Basel. They said it was the first time a Turbine Hall artist had actually come to see them to talk about the space! For me it was really important to go and see them: they’re the architects, they’re alive, they’re there. I wanted to know what they had in mind when they created the space and they said it was their idea to excavate the original building and make it even bigger and draw people in. So how did you approach your work that’s now in the London Underground?

LG I knew what I wanted to do immediately, like you knowing how to play with those big spaces. I wanted access with no restrictions. I asked for a pass so I could film everywhere. It’s not easy to do that, but it was all I needed, and they agreed – they were happy to let me just gather material. I filmed on the Victoria Line, which opened in 1968. The title of my work refers to Robert McNamara – a character I have worked with since 1992. He was US Secretary of Defense at the height of the Vietnam War and became President of the World Bank in 1968. When ‘68’ was happening in Paris, you also had McNamara moving from the control of war to the control of global finance.

I looked for traces of the original 1968 architecture all over the Victoria Line stations and I’d find certain fittings, little areas of grey tiles and the wood on some benches. In the end I used every piece of footage I shot and compressed it into one rapid section – I was thinking of the trailer for Godard’s Film Socialisme (2010). Then I chopped the footage into 16 ten-second sections: different trailers for a potential movie about McNamara. It’s shown as you go down the escalators between adverts for holidays and face cream. Where there used to be posters now there are films. There’s a correspondence with your work Philippe. It’s like an announcement for something that hasn’t happened yet. Something to come.

Hyundai Commission: Philippe Parreno opens in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall on 4 October.

Philippe Parreno will be speaking with Nancy Spector on 6 October as part of Frieze Masters Talks. For details and the full schedule see here.