Portfolio: Bouchra Khalili

Roberto Rossellini, Ousmane Sembène and an inverted atlas

Roberto Rossellini, Ousmane Sembène and an inverted atlas

Muhammad al-Idrisi’s world map

‘I believe that the first image that counted for me, and came to be almost the ultimate image, was not an image of film, but an atlas of geography.’

This is a quote from the seminal French film critic Serge Daney, taken from Itinéraire d'un ciné-fils (Journey of a ‘Cine-Son’, 1999). When I heard it for the first time, I immediately made it mine.

This map of the world was drawn by Muhammad al-Idrisi. As a child, I often saw it in history books about the Islamic Golden Age, and I consider it the first image that really counted for me. While for decades Al-Idrisi’s Tabula Rogeriana (c.1154) was considered the most accurate atlas produced, what has always fascinated me is the beauty of these maps and the potential narratives they suggest. In this particular map, it is the Mare Internum that literally encircles the land, the strange articulation of schematic landmarks that reference the Islamic miniature tradition, and the extraordinary refinement of the drawing and the calligraphy. It all comes together to suggest a map of a lost Atlantis. If I were using filmic language, I would say that I see this map as less of an ancient tool of knowledge than a magnificent syncretic combination of signs suggesting an accurate yet imaginary and poetic projection of the world.

What is certainly most surprising about this particular image is its orientation: the map is literally upside down. As some of the earliest maps are from the Muslim world, they were produced by scholars and were oriented from the Middle East. Retrospectively, what I learnt most from this map is that geography has always been – and always will be – a political product, a mirrored reflection of power. It can be a subjective production, literally reversing the perspective of power to provide another representation, narration and reflection.

The Taking of Power by Louis XIV, 1966

If the first image I really saw was an atlas, the first film was Roberto Rossellini’s The Taking of Power by Louis XIV (1966). It was accidental. I was eight year old, and on a day off my parents decided to take me to a cinema that was screening films for kids. The film belongs to the last period of Rossellini’s work (the most ignored and underrated part of his filmography), which he defined as ‘didactic cinema’: films exclusively produced for TV as democratic, educational tools for the public. The title says it all: it was a film about history, and my parents thought that actually learning something was a pretty good reason to head to the theatre.

At the time, I didn’t feel that the film offered a re-enactment of history, nor an experience of identification, nor an entertaining story (the film can definitely seem boring); it was an experience of a different kind. The account was happening here and now, as if in real-time. As a child, not fully understanding what was going on, I saw felt and experienced that history as part of my own reality, even if the narrative was about the invention of a political regime in 17th century France.

When I saw the film again some 20 years later I was still impressed by its power, but I was also able to recognize the extreme precision of the framing and the visual composition; the series of tableaux that obviously refer to 17th century French painting but are filmed in a radical documentary style.

This scene shows the first public appearance of King Louis XIV after he imposed a new dress code for his court and the nobility. Having extended Versailles, he compelled 15,000 aristocrats to relocate to his Palace. Protocol and etiquette were now strictly ritualized, with every single moment of the King’s life representing a theatrical presentation with courtiers forming a passive audience. Dressed in sumptuous garments, he’s the centre of attention at all times, around which every frame is composed.

Louis XIV says in the film: ‘Minds are governed more by appearances than by the true nature of things.’ This is ultimately what this still shows. To establish and impose, power requires a strict system of representation. It is both a theatrical scene and a manufactured image.

Appunti Per Un’ Orestiade Africana (Notes Towards an African Orestes), 1970

Pier Paolo Pasolini often claimed: ‘Cinema is the written language of reality’. From the position of poet, writer, filmmaker and heretical semiotician, Pasolini theorized a ‘cinema of poetry’, a site where the subjectivity of the author eventually merges with the subjectivity of the characters.

For years I’ve been fascinated by this idea of the cinema of poetry and its corollary, free indirect speech. In a film, who actually speaks? I have always felt that this question was somehow more crucial for documentaries than ‘fictional’ films, despite the fact that Pasolini in his writing never referred to his own work but to fictional films made by the likes of Michelangelo Antonioni and Jean-Luc Godard.

This is an image from Appunti per un Orestiade Africana (Notes Towards an African Orestes, 1970), probably my favourite of Pasolini’s extraordinary masterpieces. From the mid- to late-’60s, Pasolini dreamt of a great poem for the developing world, Appunti per un Poema sul Terzo Mondo (Notes on a Poem for the Third World), a series of films partly concerned with fragment and incompletion: films of planned films to make; a series of notes and locations scouting.

In a voice-over, Pasolini envisions how he would implement his Oresteia in Tanzania and Uganda to metaphorically and poetically investigate the future of newly independent African nations. Literally selecting from a crowd, he isolates faces and bodies that could embody Oreste, Agamemnon, Pylade, Clytemnestra. But the film can also be seen as a meditation on the performative power of speech and poetry. ‘This is Oreste’, ‘This is Clytemnestra’: poetical and magical invocations opening up to an invisible second film, a film that would only ever exist in the imagination.

Framing the casting and the location scouting, Pasolini engages in a dialogue with Roma-based African students, inviting them to comment and criticize his ‘Appunti’, or ‘notes’. This is why this work means so much to me: Pasolini opens himself up to examination and criticism from those who he aimed to speak for as a poet and filmmaker. Illuminating the inherent conflicts of his own position, Pasolini creates a platform for a cinema of poetry in which the subjectivity of the author and that of his characters can meet. The ‘Orestiade’ will never be filmed, but what remains is an environment in which author and characters speak for themselves, but all together.

Black Girl, 1966

This image is taken from the very end of Black Girl (1966), the first feature film from the self-educated writer and filmmaker Ousmane Sembène, the first African filmmaker to gain international recognition. Black Girl depicts the tragic fate of Diouana, a young Senegalese woman who finds employment as a governess for a French family based in Dakar, and travels with them when they relocate to Antibes in southeastern France. There Diouana is no longer a governess but a maid, tasked with taking care of the two children, cleaning, cooking, serving meals and fulfilling the role of an African servant shaped by a colonial gaze. To use Pierre Bourdieu’s words, Dounia is ‘spoken more than she speaks’.

The film shows two irreconcilable perceptions: Madame and Monsieur speaking about Diouana as if she were absent, and Diouana developing a contrary inner monologue; a poignant study of loneliness, racism and exploitation. She realizes that shifting from the position of former colonized to immigrant worker changes nothing. Class, race and gender divisions are reformulated within the domestic space, preserving the power structures on which the colonial society was built, and on which a postcolonial society similarly relies.

Isolated and hopeless, Diouana finds escape in suicide. Amongst the personal belongings that Monsieur delivers to Diouana’s bereaved mother in Dakar is a mask. The mask was probably the object for which Diouana cared the most as it followed her whole trajectory – the film can also be seen as the description of the circulation of this mask. This still shows the young Ibrahima, a relative of Diouana, who has witnessed the encounter between Monsieur and Diouana’s mother. When Monsieur has left, Ibrahima puts on the mask and follows him into the streets of Dakar. Frightened, Monsieur picks up the pace while Ibrahima tracks him, calm and resolute. What always impresses me about this overwhelming and uplifting final scene is this fantastic sense of visual synthesis that Sembène produces. Ibrahima represents a new generation of resolute and self-assured Africans, and while Diouana may have lost herself in the West, the mask is back where it belongs, ‘not as a mystical symbol as it could have been to our previous ancestors’, Sembène says, ‘but as a symbol of unity and identity and the recuperation of our culture’.

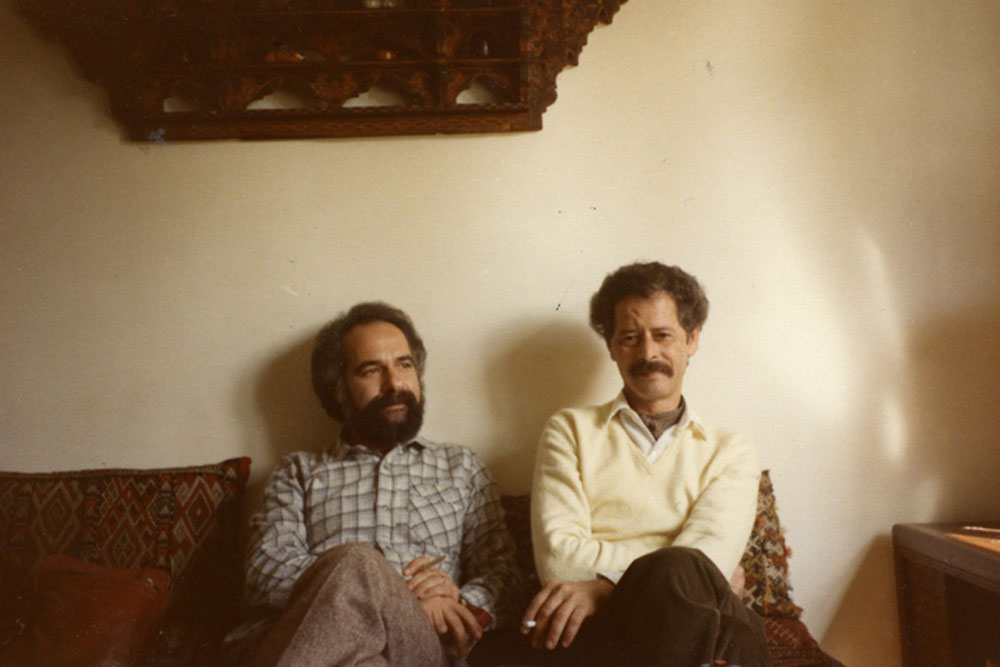

Abdellatif Laâbi and Mohamed Choukri in Rabat, 1984

I like imagining this picture is from a family album; as if I’m looking at a pair of uncles. Seated next to each other in what seems like a traditional Moroccan living room are two majors Moroccan writers. On the right is Mohamed Choukri, a radical novelist and chronicler of his hometown of Tangier. Born in 1935 in a village in the Rif, he arrived in Tangier at the age of seven and lived on the streets. Speaking only Tarifit (the language of the Riffians) at first, he quickly learnt dialectal Arabic but was illiterate until the age of 20.

In his novels, Choukri describes with rage the lives of the oppressed. In a rebellious mixture of classical and dialectal language, he wrote what is still one of the most controversial and subversive Arabic texts: Le Pain nu (For Bread Alone, 1973). The novel was banned in Morocco for almost 30 years, but when it was finally released in the early 2000s we had all already read it, either in its English translation or in Tahar Benjelloun’s French translation from 1980.

On the left is Abdellatif Laâbi, the son of a craftsman. At the age of seven he attended a French school in his native Fez, an opportunity only a few Moroccans enjoyed in the late ’40’s, and later became a professor of French. Each of his works, whether poetry or prose, is an elegant and subtle meditation on universal freedom and equality.

In 1966, Laâbi founded the legendary magazine, Souffles. From 1966 to 1972, the magazine gathered together the most talented Moroccan poets, novelists, filmmakers, artists and activists, as well as artists and intellectuals from all over Africa and the Middle East, to explore the question: How do we shape a decolonized modernity for North Africa and the developing world?

During that same period, Laâbi also co-founded the leftist underground party Ila Al Amame, which saw him imprisoned for eight years. I’ve always known of Souffles, even during the 40 years when it was almost impossible to find issues of the magazine in Morocco. It has always been recalled as the stuff of legends and old tales, but last year, thanks to Laâbi’s persistence, the Moroccan National Library finally uploaded all of its back issues onto its website.

Morocco is often depicted as ‘a country between tradition and modernity’ and when I look at this picture what I see are two moderns, ‘more modern than any modern’, to quote Pasolini. I do not see two guards of tradition who strived to enter into modernity, but two bearers of a force of the past that ultimately allowed them to be ‘more modern’ than any.