Post-Truth Detroit

Culture Lab Detroit’s post-truth conference, the ‘Art of Rebellion’ show and Pope.L’s Flint Water Project

Culture Lab Detroit’s post-truth conference, the ‘Art of Rebellion’ show and Pope.L’s Flint Water Project

Near the passenger exit of Detroit Metro Airport hangs an unmissable red banner, emblazoned with Detroit’s motto, ‘America’s Great Comeback City’. As he drove me to my hotel, my taxi driver echoed the sentiment of the banner, with one exception: ‘The schools aren’t coming back yet, because so many people moving here are single.’ The statement seemed pitched directly to me – a young white woman travelling alone to artsy Corktown, a once-desolate neighbourhood surrounding the shuttered Tigers Stadium. Today, it serves as a photogenic symbol of Detroit’s cultural revitalization, populated by restaurants, record stores and bars with nods to the city’s industrial past. Gentrification feels spectral outside the city centre, however, as Detroiters struggle with basic infrastructural issues such as blight and water shortages. According to 2016 census data, the population of the 139-square-mile city totals just 672,795 residents. And as The Centre for Michigan reports, 27,552 Detroiters experienced water shutoffs due to unpaid bills in 2016 – almost one in six residential accounts – and up to 18,000 residents may be subjected to shutoffs this year.

I came to the Motor City under the auspices of Culture Lab Detroit, a non-profit organization that seeks to engage local art and design communities with international artists, architects and visionaries around pressing social concerns. Founded in 2012 by Jane Schulak, a Detroit-born designer whose professional expertise includes stints at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, Culture Lab Detroit hosts free annual dialogues with internationally recognized participants.

This year’s sessions were organised around the buzzy theme of ‘Post-Truth’. Schulak explained that she chose the subject without the aim of political agitation, and yet politics inevitably dominated the discussions. The first night’s panel, moderated by Juanita Moore (CEO and president of Detroit’s Charles H. Wright Museum for African American History), included Los Angeles artists Edgar Arceneaux and Martine Syms, and the New York–based designers Christopher and Dominic Leong (of the firm Leong Leong). Titled ‘Alternative Facts’, the panel circled around the way rhetorical strategies in contemporary politics intersect with artistic practice. Arceneaux spoke about the choices undergirding Until, Until, Until… (2015), his live restaging of Ben Vereen’s blackface performance at the 1981 inauguration of President Ronald Reagan. Arceneaux’s touring play includes a second-act critique of blackface that was purposefully omitted from television broadcasts in 1981. Syms professed her desire to continue to work in alternative spaces and contexts, as major art institutions often promote her work as a black female artist in the name of diversity, while failing to fundamentally restructure their programs towards true inclusivity. The Leong brothers, too, expressed a disconnect between the progressive ideals behind many contemporary architecture practices and the common exclusivity and political apathy of the profession.

The second night’s panel, ‘The Lie That Tells The Truth’, took its title from a Pablo Picasso quote about the function of art. That evening’s conversation was decidedly more poetic in its framing, from its title to its location: the soaring 50,000-square-foot Woods Cathedral purchased by New York design-dealer Paul Johnson in 2014 for just $USD 6,700. At present, the church exemplifies Detroit’s aesthetic of romantic decay. Johnson has presided over a roof repair and structural upgrades to accommodate a crowd, but the edifice still features crumbling plaster and original fixtures, and no running water. For Culture Lab, Detroit-based artist Matthew Angelo Harrison installed a series of pew-like benches in the nave, comprised of clear acrylic bars (nodding to designs by Herman Miller, a Michigan-based company) spearing bones of African animals. Harrison’s reference to Detroit-area industrial design also uses bars to connect incarceration with environmental violence. Harrison also produced glitched (twinned, squashed or otherwise corrupted) African masks and objects live in the space, using a homemade 3D printer.

In a talk that headlined the conference and chaired by President & CEO of United States Artists, Deana Haggag, writer Hilton Als and artists Mel Chin and Coco Fusco agreed that fictions, in the form of collective storytelling, nationalism and religion, were necessary in the production of art and politics. The evening concluded with a spirited Q&A, in which one audience member asked why art and protest had to adopt the strategies of mass culture. Fusco replied that protest culture had turned toward spectacle since the 1999 World Trade Organization demonstrations in Seattle. ‘What you’re asking for is a return to citizenship that disappeared when we became consumers,’ she said.

Detroit and its surrounding areas present a case study in urban decline – one that has spurred many artists to work directly with local communities. In Flint, Michigan, for example – a once-thriving industrial city and now a symbol of post-industrial neglect and government corruption – an ongoing crisis over contaminated water has prompted several artist responses. When the local government turned to the Flint River as a water source in 2014, taps became disastrously polluted, causing infertility, birth defects, disease and even death. As of January 2017, the water in Flint has been declared safe in terms of its lead and copper levels, though residents still have been warned to wait at least a year before drinking it, due to pipe corrosion. For his Flint Fit (2017) project, Mel Chin has collected water bottles from Flint residents, which will be recycled into fabric, printed with designs for rainwear and swimwear by New York designer Tracy Reese, and stitched by workers in Flint. Chicago-based artist Pope.L has approached the water crisis more conceptually; his Flint Water Project (2017), on view at the artist-run space What Pipeline in south-west Detroit, sells cases of water collected from Flint at prices ranging from $20 for an unsigned bottle to as much as $5,000 for a case of 24 signed bottles. In the small garage-like space, bedecked with Flint Water wallpaper and artwork by What Pipeline’s collaborators and friends, workers wearing goggles, gloves and aprons pack up cases at a bottling station. All the proceeds directly benefit Flint residents, through the organizations United Way of Genessee County and Hydrate Detroit.

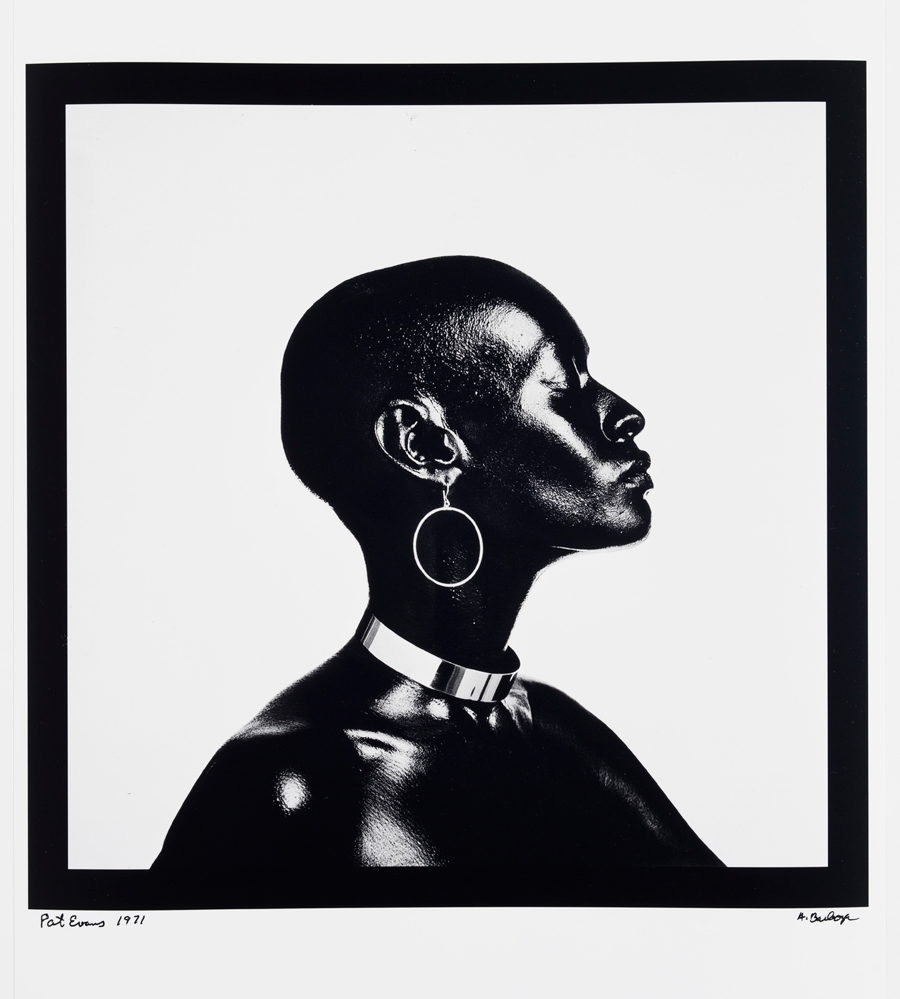

Given the city’s predominantly black population, the failure of Flint’s infrastructure has been framed by many as an example of racial injustice. Two current museum exhibitions in Detroit give this some historical context, by commemorating the 50th anniversary of the 1967 Detroit uprising, which was ignited by mounting frustration over police brutality and racial discrimination. At the Detroit Institute of Arts, the exhibition ‘Art of Rebellion: Black Art of the Civil Rights Movement’ includes a didactic video about the Detroit Rebellion. The show spans works by collectives from the 1960s – such as New York’s Spiral and Weusi groups and the Chicago-based AfriCOBRA – to contemporary artists like Adam Pendleton, whose sweeping installation Black Lives Matter #3 (2015) fills an entire gallery. At the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit, a more-is-more sensibility plays out in ‘Sonic Rebellion: Music as Resistance’. At once paying homage to Detroit’s radical past and contemporary artists’ focus on music culture, the show includes nearly 40 artists and several dozen contributors from music and broadcast media. The exhibition highlights many productions that wouldn’t typically be considered art, from public access shows devoted to R&B and soul, to 1980s house music ephemera, to 1960s countercultural graphic design. The art offerings are exciting yet diffuse. Many artworks respond directly to the musical premise, such as a video by Mickalene Thomas with black female entertainers (Do I Look Like a Lady? (Comedians and Singers), 2016) and an installation by Jamal Cyrus about a fictional LA record store that turned its sales from Black Power music to punk rock. Other works, however, feel tangentially related, such as a photograph by Hank Willis Thomas appropriating the form of a MasterCard ad (Priceless, 2004), or Pedro Reyes’s video Disarm (2012), in which musicians turn guns into instruments.

‘Sonic Rebellion’ is well-intentioned, though its overly broad curatorial strategy risks romanticizing Detroit’s past. In a city with its eye focused eagerly on the future, unchecked nostalgia can be a trap. Now more than ever, it’s important to tell these stories; but if we’ve learned anything from this ‘post-truth’ era, it’s that the way we tell them makes all the difference.

Main image: Adam Pendleton, Black Lives Matter #3 (detail), 2015, installation view ‘Art of Rebellion: Black Art of the Civil Rights Movement’, 2017, Detroit Institute of Arts. Courtesy: Detroit Institute of Arts