Postcards from Venice pt. 5: Surrealist Pro-enactments

Re-enactment and Pro-enactments a theme of the 54th Venice Biennale

Re-enactment and Pro-enactments a theme of the 54th Venice Biennale

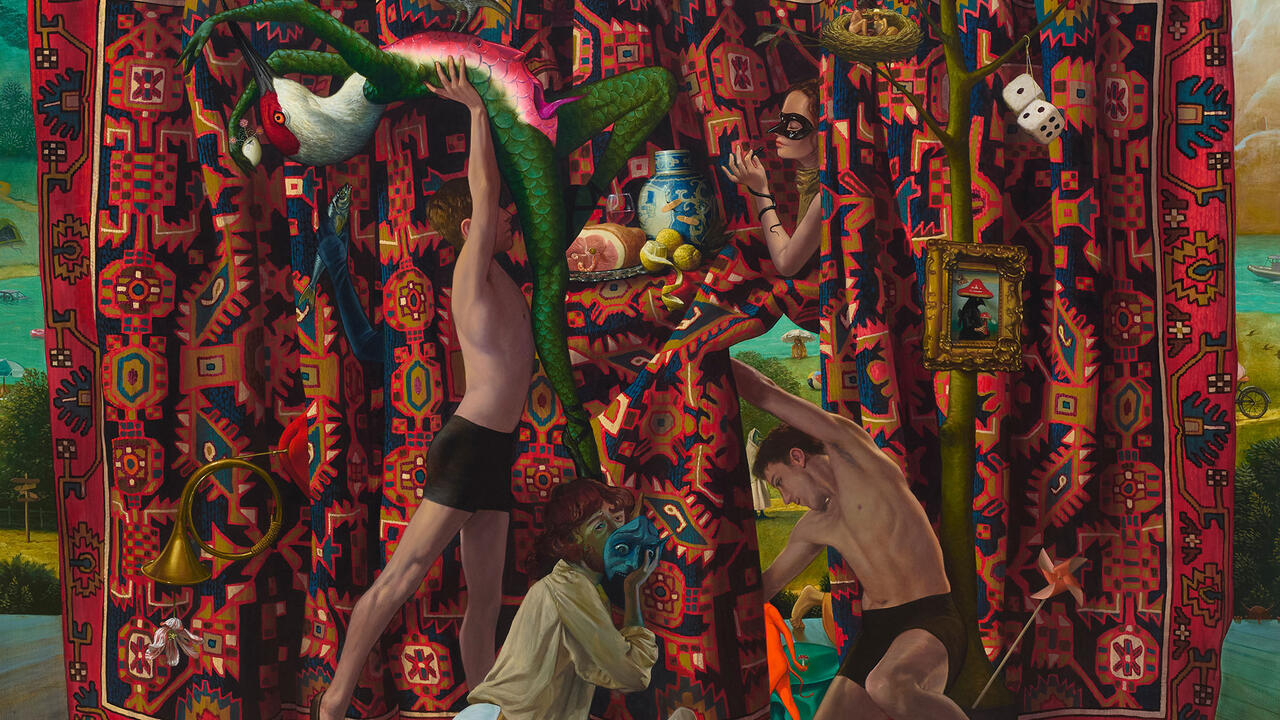

The main observation I took home with me from the 54th Venice Biennale was that some of the best work on show combined two elements: rather than re-enactments of previous events (as in so many art works of recent years), they involved what could be called pro-enactments – newly imagined scenarios and combinations of things hitherto unseen, unknown, unimagined. And they did so on the basis of a Surrealist understanding of film and enactment.

The seminal historical work in that regard was Czech director Jan Švankmajer’s amazing short film The Garden (1968), on show in the Danish Pavilion’s group show ‘Speech Matters’, which looked at issues of political free expression. The story is a simple allegory: a guy who owns a car takes another fellow with him to his country house. It turns out that the country house’s fence is in fact a human chain; even the gate is composed of ordinary citizens who make way for the car the way a gate would do, and whom for mysterious reasons remain in position as if brainwashed. The system of repression clearly relies largely on the hectoring of the individual, suggesting their guilt of having failed to fulfil impossible demands; at one point the owner of the house takes a rabbit by its neck and shows it to his guest, whom, as one might have suspected, will soon join the fence. What is so amazing about Švankmajer’s 16-minute film is how – while clearly belonging to the Luis Buñuel tradition in its allegorical set-up – it predates by decades the Lynchian techniques of horror and intimidation: super-macro close-ups on banal everyday acts like wiping the nose or opening the mouth; the soft-spoken voice as the threat of ultimate sadistic power; the camera that, in the flow of images, remains ‘too long’ on someone’s face, making it eerily feel nightmarish, literally sur-real.

Švankmajer’s allegory of a totalitarian CSSR created on the eve of Prague Spring made clear, if one needed to be reminded of it, that Surrealism is an artistic mode borne out of a throbbing discontent with systematic forms of repression. Dominik Lang’s Czech Pavilion, in which he incorporated sculptures by his own father into a complex installation, seemed to present us with echoes of this past.

But it was more obvious in the case – given a similar political context – of the 1970s work of Moscow’s Collective Actions Group, shown in the Russian Pavilion curated by Boris Groys. The first action they realized involved people being asked to gather on the edge of a forest where an unspecified event would take place (_The Appearance_, 1976). As nothing seemed to happen, they eventually went home; but as they received photographs of themselves on site through the mail, it turned out that their own appearance had been the actual event. The work anticipated today’s tautology of audience attention and event, but it also subtly, surreally echoed the harsh reality of surveillance and control.

But that surrealism directly responds to repression became even more clear with Israeli artist Yael Bartana’s Polish Pavilion, and the Egyptian Pavilion dedicated to the memory of artist and activist Ahmed Basiony (1978–2011). Bartana’s ambitious film trilogy envisions the founding and the activities of the ‘Jewish Renaissance Movement in Poland’ (JRMiP), a political group that calls for the return of 3,300,000 Jews to the land of their forefathers. The piece obviously hits the trauma buttons of at least two nations: Poland’s slow and late coming to terms with its role in the Holocaust, and its postwar anti-Semitism leading to the exodus of almost all remaining Jews; Israel’s policy of defining its military role in the region as, ultimately, the task to prevent a second Holocaust, manifested by Israeli high school classes going to Auschwitz and the Ghetto Uprising Memorial in Warsaw directly before entering the Army.

What is quite amazing about Bartana’s trilogy of short films is how it effortlessly holds up the impression that these things were indeed actually taking place: the leader calling for the movement to be founded; the actual installment of a Zionist settlement in the middle of Warsaw; and the assassination of the leader, his heroic death manifested in a ridiculously huge outdoor bust, and with the means of Socialist-Realist pathos. The logo of a Polish eagle conjoined with the Star of David in itself is a kind of Surrealist emblem (I witnessed a woman asking the press person whether the movement actually exists, and when the answer was somewhat sibylline, she became quite agitated and suspected the movement to be fascist at root).

The one issue one might take aesthetically with Bartana’s trilogy is that all in all it maybe too readily employs the crisp language of contemporary film – the smooth dolly shots, the perfectionism of the staging and sound etc. – as if to prove that Hollywood would be an option. Omer Fast’s The Tunnel (2010) about a remote pilot of US un-manned drone planes is similar in that regard (shown in Bice Curiger’s curated part of the Biennale). It works with sophisticated cinema effects, but maybe it would have worked better for me without the added element of carefully staged actor re-enactments, when the interview material in itself was already so strong. Sometimes realism is the better surrealism.

In the Egyptian Pavilion, what we were confronted with was essentially a documentary video installation showing us the last major piece of Ahmed Basiony, realized less than a year before he was shot by an Egyptian Police Forces sniper on 28 January in Tahir Square, and original footage Basiony had taken during the demonstrations. This was a moving testimony, but it also uncannily envisioned the relationship between the oppression of the individual and the uprising of the masses. Basiony’s piece involved him running on the spot clad in a futurist plastic outfit, his head covered in a transparent plastic sack, as if he was a kind of astronaut threatened by suffocation, while electronic devices tracked and translated his movements into a digital visual representation. It’s as if he anticipated that this tracking and translating of the individual’s movements and motivations via digital social media could become the most powerful weapon of an actual movement.

That Surrealist aesthetic modes may come directly out of experiences of systematic repression however is not something restricted to the environments that feature the more obvious forms of state violence. Class issues for example underlie the perverse elegance of Markus Schinwald’s Austrian Pavilion featuring a maze of ceiling-suspended walls leading to surreally enhanced found paintings, and to video works involving feet stuck in walls, and pratfalls turned tap-dance; as well as Nathaniel Mellors’ hilarious and well-acted filmic scenarios (part of the Curiger show), transposing the British class question into a visual reverie worthy of Monty Python and Nicolas Roeg alike.

The late Christoph Schlingensief’s early films made in relatively peaceful pre-‘89 West Germany are also a case in point – repression never goes entirely away, it just takes on other forms. The films are on display, in newly restored and subtitled editions (thanks to curator Susanne Gaensheimer), in one of the two side rooms of the German Pavilion – which won the Golden Lion for its staging of Catholic martyrdom, based on Schlingensief’s own hometown church, which he had already used as a stage set for his ‘Fluxus Oratorium’ (_Church of Fear_, 2008). I felt that this readymade Gesamtkunstwerk gesture, though moving because of Schlingensief’s willingness to confront us with his imminent death of cancer, didn’t do justice really to his anarchic energy which was so much better manifested in his works for cinema and television than in his Beuysian environments sold as his ‘fine’ art; all of this almost called for him to be his own heretic, a function his early films greatly fulfilled. Menu Total (1985–6) for example – shot in black and white – clashes Fassbinder with Dr. Mabuse, Buñuel with Louis de Funes. A film that you can imagine, when it was first screened, must have made people either be outraged for being confronted with such bonkers stuff, or die laughing (if in the right mood for it).

Who would have thought though that one country would manage to transform its pavilion into an actual, not imagined nightmare of surreal repression – the Italian Pavilion with its purgatorium of bad art, curated by notorious TV-macho-critic and Berlusconi friend Vittorio Sgarbi, with individual artists chosen by such luminaries as Giorgio Agamben (proving again the well-known fact that some of the most eminent philosophers have the worst taste in art; while in this case obviously also little or no political instinct) or Ennio Morricone (who chose Sergio Leone’s daughter Francesca with her terrible oil paintings, proving once more that nepotism is most charming when it’s obvious). I realized why Sgarbi, during the opening days, was continuously fidgeting around amidst the Pavilion, hectically going back and forth, followed by cameras and/or entourage, when I eventually saw Frances Stark’s hilarious VR-sex-chat-video at the back of Arsenale. In-between scenes apparently based on an actual online romance she engaged in with a young man from Rome, transformed into moving image using cheap animation by the website xtranormal.com

She used a famous scene in Federico Fellini’s 8 ½ (1963) in which Marcello Mastroianni plays the director suffering writer’s block, followed around hectically by a group of journalist in the run-up to a press conference about his next movie. Sgarbi does nothing but an exact emulation of Fellini’s Mastroianni, albeit devoid of the grace and inspiration.

All of which seems to indicate that these are indeed times for a kind of humorously and politically charged, media-savvy neo-Surrealism.