Prospect New Orleans: Carpetbagging the Crescent City

Travis Diehl on the successes and failures – both past and present – of the young triennial in its attempt to revitalize the city in the wake of climate disasters

Travis Diehl on the successes and failures – both past and present – of the young triennial in its attempt to revitalize the city in the wake of climate disasters

When Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans in 2005, it claimed more than 1,800 lives and wreaked havoc to the tune of US$155 billion. The storm also ripped the scabs off America’s historical wounds to expose terrible inequality. Since then, the infamous Louisiana Superdome – where up to 30,000 residents were forced to shelter for days in appalling conditions – has been renamed by Mercedes-Benz, then Caesars Entertainment; gentrification creeps apace through the traditionally working-class neighbourhoods of Bywater and the Tremé (although potholes remain unfilled and schools closed since well before Katrina); and the decimated Lower Ninth Ward stays fallow, its overgrown lots mired in red tape as much as vines. Many deed-holders can’t be found, and where the owners would rather not endure due process, they sell to the city for a pittance. So it’s hard not to feel the barbs in the title of the local art triennial, launched shortly after Katrina in 2008: Prospect. A signal of hope, yes, but also a word for surveying real estate and for financial speculation. Is the Crescent City waxing or waning? And who will come out on top?

While boosterish art blockbusters proliferate around the world, Prospect might be unique in naming tourism as its explicit purpose in a bid to boost the city’s economy. The Prospect website says each edition attracts 100,000 visitors and generates US$10 million in ‘economic impact’, including ‘US$800,000 in municipal and state tax revenue’. (For comparison, the tourism sector overall brings New Orleans US$10.5 billion a year.) However, while passing through Venice for the Biennale is one thing, washing up with a sculpture in the Lower Ninth Ward before receding to one of the country’s other two coasts is entirely another. Accordingly, at Prospect, the usual guilt born of ‘parachuting in’ artists for a group show is uniquely palpable. To be fair, many have made efforts to improve the lives of NOLA residents in more concrete ways than art allows. For instance, according to the Prospect.5 website, Houston artist Adriana Corral has scrapped her original proposal in order to ‘work directly with those communities’ impacted by Hurricane Ida – the Gulf Coast’s most recent megastorm – presumably funnelling her commissioning fee straight to the grassroots.

With lessons learned from Prospect.1 (artistic director Dan Cameron’s original roster of world-class talent was duly criticized for including just 11 Louisiana-based artists out of 80), subsequent editions have all nodded to local spaces and ‘satellite’ shows. In this respect, the runted Prospect.1.5 – a city-wide celebration dreamed up to plug the gap between Cameron’s Prospect.1 and Prospect.2, which largely outsourced the curation to local galleries and collectives – was a surprise success. Similarly, both Franklin Sirmans and Trevor Schoonmaker, who respectively took the reins for Prospect.3 and Prospect.4, sought to deepen the triennial’s relationship to its host city, beyond economic improvement and the obvious local signifiers of Mardi Gras and gothic decline, in an attempt to update Prospect’s raison d’être.

Now, buffeted and delayed by COVID-19 and Hurricane Ida, there is Prospect.5. The show, curated by Naima J. Keith and Diana Nawi, is titled ‘Yesterday we said tomorrow’, and comes with a sense of deferred payoff, not to say justice. (Demography-watchers will note that Prospect.5 is the first iteration curated by women.) After all, yesterday’s tomorrow is today. The political vector of this edition feels concerned not just the revival of New Orleans but with the city as a metaphor for the country as a whole. The most pressing issues of the moment – conservative backlash, racial justice and climate change – manifest here in boldface. The city has been a major port for centuries, slumping into the Mississippi Delta all the while, which of course means New Orleans was a hub during the slave trade. Today, the city’s class disparity and racial segregation seem like perfectly pronounced metaphors for the entire US, as the sunken Lower Ninth Ward has come to represent the plight of vulnerable, low-income neighbourhoods in an age of wild climate.

Good intentions abound, but what, for instance, can theatrical Oyster Readings (2021), by London-based duo Cooking Sections (Alon Schwabe and Daniel Fernández Pascual), tell us about warming seas when art-world punters at the 2019 Venice Biennale were sloshing around the flooded restaurants in single-use booties? At the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, the late Beverly Buchanan’s small, colourful houses built of scraps and tongue depressors felt more impactful, especially the stilted Low Country House (2010) and the egressless No Door, No Window (1988). Also at the Ogden Museum, Celeste Dupuy-Spencer’s nightmarish modern history paintings, including one of last year’s attack on the US Capitol (Don’t You See That I Am Burning, 2021), and Daywoud Bey’s lyrical HD drifts through Louisiana plantationland (Evergreen, 2021), occupy similarly satisfying ground between pointed curation and misty formalism. There is also Kevin Beasley’s project of buying property in the Ninth Ward, represented at the Contemporary Arts Center by a suite of lush graphite drawings of depopulated lots (The Lower 9th Ward I–V, all 2021).

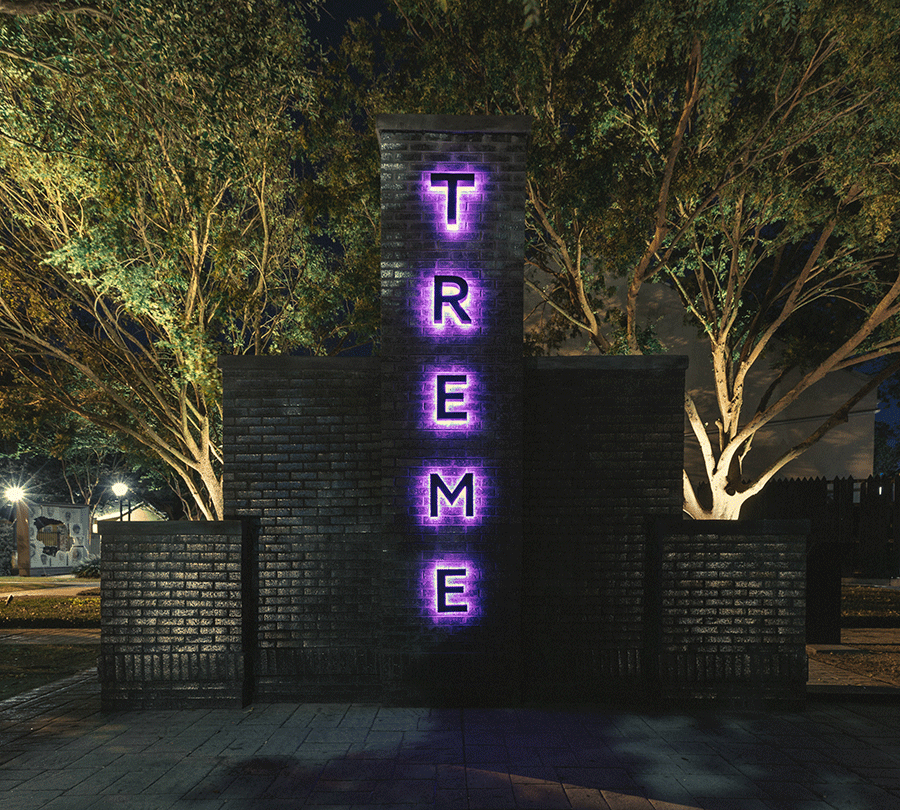

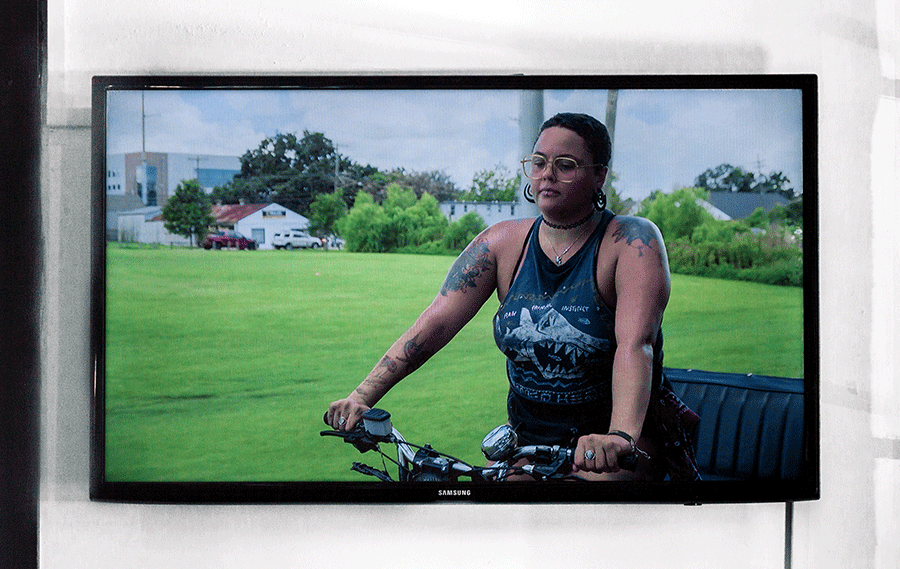

Most encouraging, then, are a handful of projects, by both art stars and regional luminaries, that address the city directly, with interventions specific to sites that felt less directed at visiting afficionados like me than at locals who pass by them daily and can intuit their context. These include Paul Stephen Benjamin’s Sanctuary (2021), a black brick and purple neon monument within the grounds of the preserved former living quarters of enslaved people in the Tremé, and Sharon Hayes’s video portraits of queer New Orleanians traversing the city (If we had had, 2021), installed in a renovated but unrented bar in Bywater – both neighbourhoods in the cambium zone of gentrification.

The other savvy trend in Keith and Nawi’s vision is self-reflection: Prospect.5 includes projects by five Prospect.1 alumni. Mark Bradford is back: his effort here is more demure, and perhaps more honest, than Mithra (2008) – his remarkably tone-deaf sculptural intervention of an ‘arc’, comprised of his signature used plywood fencing and steel shipping containers, on the site of a former funeral parlour in the Lower Ninth Ward – although just as globalist and on-brand. During the COVID-19 lockdowns, Bradford kept his studio assistants on payroll and had them mould basketballs into lumpy globes: a grid of 112 of these graces a wall of the Contemporary Arts Center (Crates of Mallus, 2021). Dave McKenzie – who, in his original project for Prospect.1, I’ll Be Back (2008), promised to return to New Orleans every year for 10 years – undertook another subtle project, to inter his father’s ashes in a local mausoleum (831-195-G Hope, 2021).

Nari Ward’s contribution, in particular, illustrates the shift in tone since the first Prospect. This time around, he’s remixed the sound collage he made for P.1 as Battle Ground Beacon (2021), a cosmic cacophony of chants, ragas, and Black affirmations emitted hourly from a mobile floodlight tower of the sort typically used by police to surveil folks in low-income areas, converted into loudspeakers. The piece didn’t feel terribly risky in the gated parking lot of UNO Gallery, gently audible from the street. Still, it will move to other sites. More importantly, I was happily excluded from the work’s main audience – New Orleanians, for whom the purring masts pumping daylight into their second-floor windows and gasoline fumes into their cobblestone streets are a daily reality. Like any well-intentioned tourist, I’ll soon head back north, my carpetbag a few dollars lighter, while the city of New Orleans will roll on.

Prospect.5 is on view at various venues in New Orleans, USA, until 23 January.

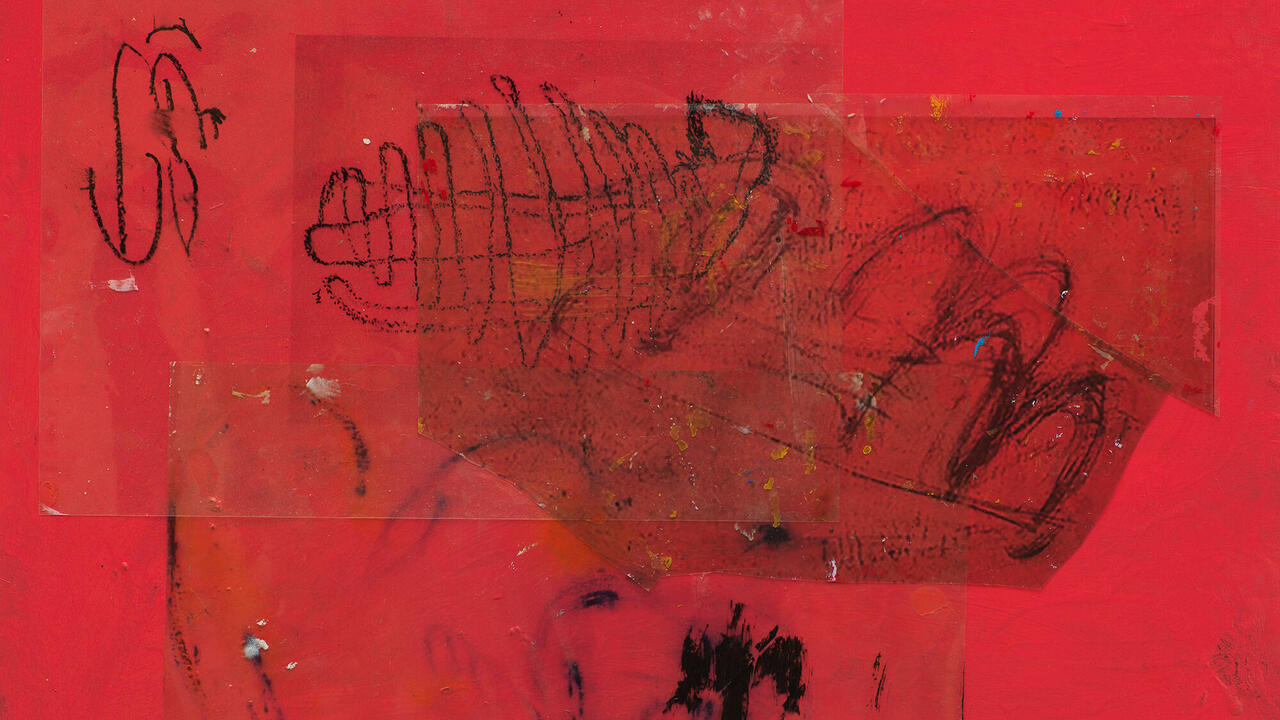

Main image: Celeste Dupuy-Spencer, Don’t You See That I Am Burning, 2021, oil on canvas, 2.2 × 2.2 m. Courtesy: © the artist and Prospect New Orleans; photograph: Jonathan Traviesa