Why Rabih Mroué Seeks to Complicate our Perception of Reality and Truth

On the occasion of the artist’s first solo exhibition in Berlin at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Carina Bukuts writes about his 20-year practice of deconstructing the image politics of war

On the occasion of the artist’s first solo exhibition in Berlin at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Carina Bukuts writes about his 20-year practice of deconstructing the image politics of war

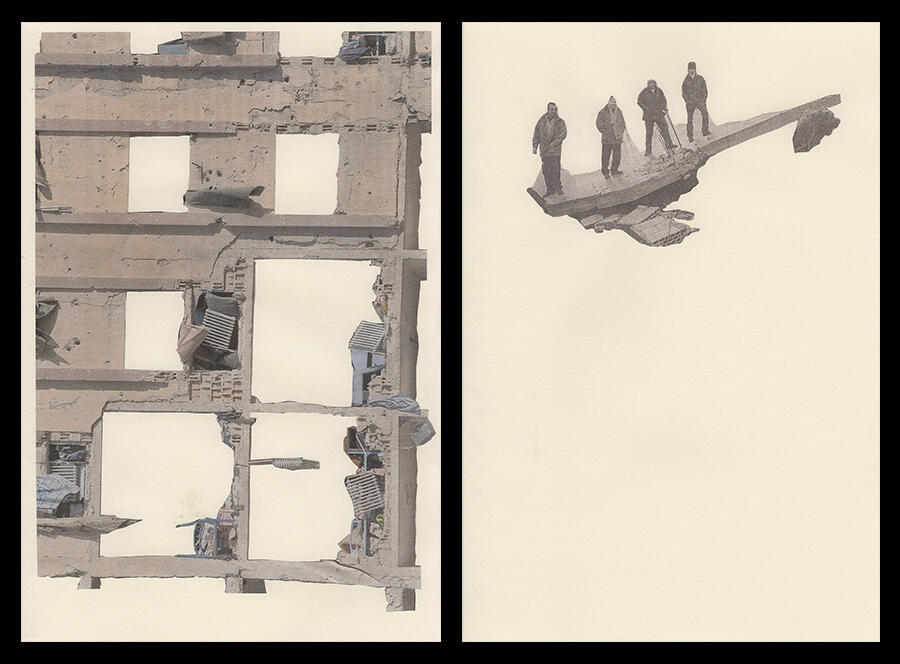

From the day the Lebanon War started on 12 July 2006, until the day Michel Aoun was finally appointed president on 31 October 2016, after more than 30 inconclusive elections, Beirut-born artist, director and playwright Rabih Mroué kept a unique diary of events in his home country. Over the course of the decade, he cut out images from Lebanese and international newspapers and glued them onto individual sheets of white paper: soldiers carrying a body on a stretcher; ships that remained in port because of a naval blockade; a forlorn-looking couple with their belongings packed in plastic bags; fragments of a barbed-wire fence; the trail of a launched missile flying past a jeep. Comprising 366 images – one for each day of the leap year in which the project was completed – Leap Year’s Diary (2006–16) is one of the central works in ‘Under the Carpet’ at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Mroué’s long-overdue solo exhibition in Berlin, the city he moved to in 2013. Removed from their original context and hung in frames across the wall, these images are stripped of the propagandistic potency the media imbues them with. Instead, Mroué leaves white space both within the collages and in the gallery for viewers to fill with their own storied interpretations.

When Mroué and I meet to discuss the show, I ask if he plans to publish an accompanying monograph. I had been somewhat surprised to realize, when looking for books about the artist to prepare for this piece, that there are currently only three from his 20-year career: a critical reader (Rabih Mroué, 2012), a publication featuring a small selection of his writings (Image(s) Mon Amour: Fabrications, 2013), and the collected works from Diary of a Leap Year (2017). Yet, after speaking to Mroué, it becomes clear that it doesn’t matter whether you read every text about his work or none. He wants visitors to look at it without previous knowledge and tells me that he always disliked the idea of having a publication that sums up his practice: ‘I don’t want people to have the impression that a book can be a toolbox to my work.’

In the late 1980s, Mroué studied theatre at the Lebanese University in Beirut and pursued a career as an actor – one of his most prominent roles saw him play alongside French film icon Catherine Deneuve in Je veux voir (I Want to See, 2008) – as well as directing his own plays. During the Lebanese Civil War (1975–90), many artists and intellectuals in Beirut turned to theatre, as it was one of the few still-tenable cultural forms. Due to the French colonization of Lebanon from 1920 to 1945, the country’s understanding of theatre was strongly influenced by Western practices. Mroué and a group of friends started to rethink performance, imagining what it might look like without costumes, without character names, and without overacting. Removing these layers and disguises shifted the focus onto the text, and the power of Mroué’s performances still lies in his brilliantly written and unpredictable scripts, which challenge the use of language and the hierarchy of linear and non-linear storytelling. Here, video installation meets photography, lecture meets performance, spoken word meets music.

In the performance Riding on a Cloud (2013), for instance, which premiered at the Rotterdamse Schouwburg, the artist paints a vivid picture of the life of his brother, Yasser, in the aftermath of the Lebanese Civil War. ‘This is my real story, yet these are not my thoughts. These thoughts are mine, yet this is not my real story,’ begins Yasser. These opening lines disclose that Mroué – and not his brother – is the author, yet also hint at the universality of Yasser’s experiences. Sitting at a desk stacked with DVDs, Yasser tells us that he lost the ability to formulate and understand speech after being shot by a sniper while crossing a street in Beirut in 1987. As with many of Mroué’s works, Riding on a Cloud blends the personal with the political. Witnessing this act of violence against his brother must have been a traumatic experience, but Mroué never exploits such events to create art about the war; rather, he seeks to complicate our perception of reality and truth. Without following any linear dramaturgy, Riding on a Cloud shows Yasser inserting DVDs into a player, one after the other, each of which shows footage he filmed on the advice of his doctor, in order to relearn how to differentiate between reality and representation. Just as Yasser has difficulties telling the difference between a photograph of a person and their physical presence, viewers are also left wondering whether the Yasser they see is an actor, the real person or both. When Yasser turns his back to the audience to watch the footage of himself, becoming a spectator of his own performance, Mroué seems to suggest that reality is always a matter of perspective.

One of Mroué’s best-known works, The Pixelated Revolution (2012), commissioned by dOCUMENTA (13), deals with the impact of mobile-phone footage recorded during the Syrian Revolution, following the Arab Spring (2010–12). The 22-minute lecture – defined by the artist as ‘non-academic’ – opens with the deeply disturbing line: ‘The Syrian protesters are recording their own deaths.’ Departing from this sentence, Mroué presents a series of videos taken by civilians and protesters showing the exact moment the anonymous filmmaker is fatally shot. The footage is heavily pixelated or blurred, while the camera frequently changes perspective, making it hard to recognize individual shapes. The fear of the person filming, however, goes straight to your bones. Yet, instead of drawing on the emotional impact of the images, Mroué looks at them analytically, zooming in frame by frame, pixel by pixel, to develop a theory on the symbiotic relationship between the camera and death – or, as he calls it, ‘double shooting’. As he explains in the piece: ‘One is shooting with a camera; the other is shooting with a rifle.’

Previously, Mroué had always refused to present recordings of his lecture-performances as part of his exhibitions, nor did he want them to be accessible online. However, during the pandemic lockdowns, he was invited by theatre spaces and festivals, such as Kampnagel Hamburg and the 2021 edition of the Bienal de Performance de Argentina, to present online screenings of his performances. It seems this experience may have altered his approach to accessibility, since a great deal of the newly commissioned works included in ‘Under the Carpet’ are performances which he restaged and recorded for this purpose. The selection includes, among others, acclaimed works such as Make Me Stop Smoking (2006), addressing the impact of war on the landscape of Lebanon, and Sand in the Eyes (2018), in which Mroué analyses the image politics of Islamist propaganda videos and what their aesthetic reveals about both their producers and their targets, mostly young, European men.

As we sit talking in a cafe in Berlin-Mitte, Mroué and I realize that his home (which is also his studio) is only a stone’s throw from frieze’s Berlin office. While his busy international schedule would ordinarily have made it difficult for us to meet, the social-distancing measures introduced in response to the pandemic have caused theatres to remain largely shut for the past two years, meaning Mroué has spent more time than usual in his Prenzlauer Berg apartment. This change in circumstances inspired the artist to develop a series of works that explore the conditions of isolation.

For Haus der Kulturen der Welt’s series of online commissions, ‘CC: World’ (2020), Mroué created Cheers to our Wishes (2020). This beautifully edited video essay combines an adaptation of French playwright Antonin Artaud’s Theatre and the Plague (1933) – which describes the first signs of the Black Death in Marseille – with a tracking shot that pans out from concrete walls and courtyards to a cityscape until it reaches the sea and, finally, the sky. Other scenes show trees reflected in a lake and a scroll-down of a partially blurred email correspondence between Mroué and his doctor, in which he notes: ‘I see everything out of focus except for one detail.’ While the correspondence looks authentic, I’m mindful of the fact that Mroué finds pleasure in suspending the viewer in a liminal state of unknowing – perhaps the most appropriate response to the events of 2020.

When preparing for ‘Under the Carpet’, Mroué tells me that the gallery architecture – a mezzanine open to the gallery floor below – made him consider how the viewer’s gaze would move from one floor to the other. Placed between both floors, the newly commissioned video Images Mon Amour (2021) shows a vertical scroll of cut-outs from Lebanese newspapers that Mroué collaged together. We see destroyed landscapes, debris, a great amount of dented oil canisters, collapsed buildings and smoke from an explosion. Unlike his earlier collage work Leap Year’s Diary, there’s no space left between the images; everything is melted together into one endless scroll, as if Mroué wanted to say events that caused the depicted damages and losses are not only all connected, but also endless.

In Lebanon, the pandemic not only quashed any hope sparked by the 2019 revolution but, on 4 October 2020, a huge explosion in Beirut harbour destroyed a vast central area of the city. In the late summer of 2021, Mroué co-curated the festival ‘This Is Not Lebanon’ at Künstlerhaus Mousonturm and Frankfurt LAB with dramaturg Matthias Lilienthal. Comprising a series of performances, panel discussions and lectures by a younger generation of Lebanese artists and thinkers, the festival sought to draw attention to the country’s precarious situation, which is rarely reported on in Western media. With hardly any fuel, no functioning power supply, high numbers of COVID-19 cases and shortages of medicine, the country is ‘in free fall’, to quote the festival literature, and the world doesn’t even seem to be watching. In the hope of changing this, the curators of ‘This Is Not Lebanon’ invited, among others, Turner Prize-winning artist Lawrence Abu Hamdan, whose performance Air Pressure: A Diary of the Sky (2021) addresses the increase of foreign supersonic planes crossing Beirut’s airspace during the pandemic.

The unprecedented experience of living in a pandemic prompted many people to turn to writing as a way of comprehending what was happening around them. First presented as part of Kunsthalle Mainz’s virtual programming during lockdown, A Reconstruction of a Diary (2020) is a series of scans from Mroué’s personal journal entries compiled in March and April 2020. In early March, we learn that he went to Spain for the festival Punto de Vista, where he met with artist Éric Baudelaire to speak about collaborating on a new film. Back in Berlin the following week, on 10 March 2020 Mroué notes – in red ink – that he’s not feeling well and has symptoms of COVID-19. Throughout the following pages, the word ‘cancelled’ is written in capital letters over all events, travel plans and meetings. We read how he notices he has lost his sense of smell while cutting onions, how he reminds himself to check on family and friends in Beirut, and his poems and observations about the state of the world: ‘These days seem to me like a sci-fi movie and we are all playing a part in this film. The good thing is that there is no hero. We are all playing the role of extras, knowing that, in this movie, crowd scenes are forbidden. We are extras but isolated from each other.’ While Mroué’s work often features aspects of his personal life, A Reconstruction of a Diary is disarmingly raw and honest. However, if there’s one universal takeaway from Mroué’s attempt to deconstruct images and words, it is that you can never be certain of what you see and read. It might just be that the truth has been swept under the carpet.

Rabih Mroué's solo exhibition 'Under the Carpet' is on view at KW Institute of Contemporary Art, Berlin until 1 May.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 225 with the headline ‘Rabih Mroué’.

Main image: Rabih Mouré, Before Falling Seek the Assistance of Your Cane, 2020, video still. Courtesy: the artist and Künstlerhaus Mousonturm, Frankfurt am Main