Rashid Johnson’s Directorial Debut, ‘Native Son’

Why has the artist chosen to adapt a novel that has been criticized for its portrayal of Black characters?

Why has the artist chosen to adapt a novel that has been criticized for its portrayal of Black characters?

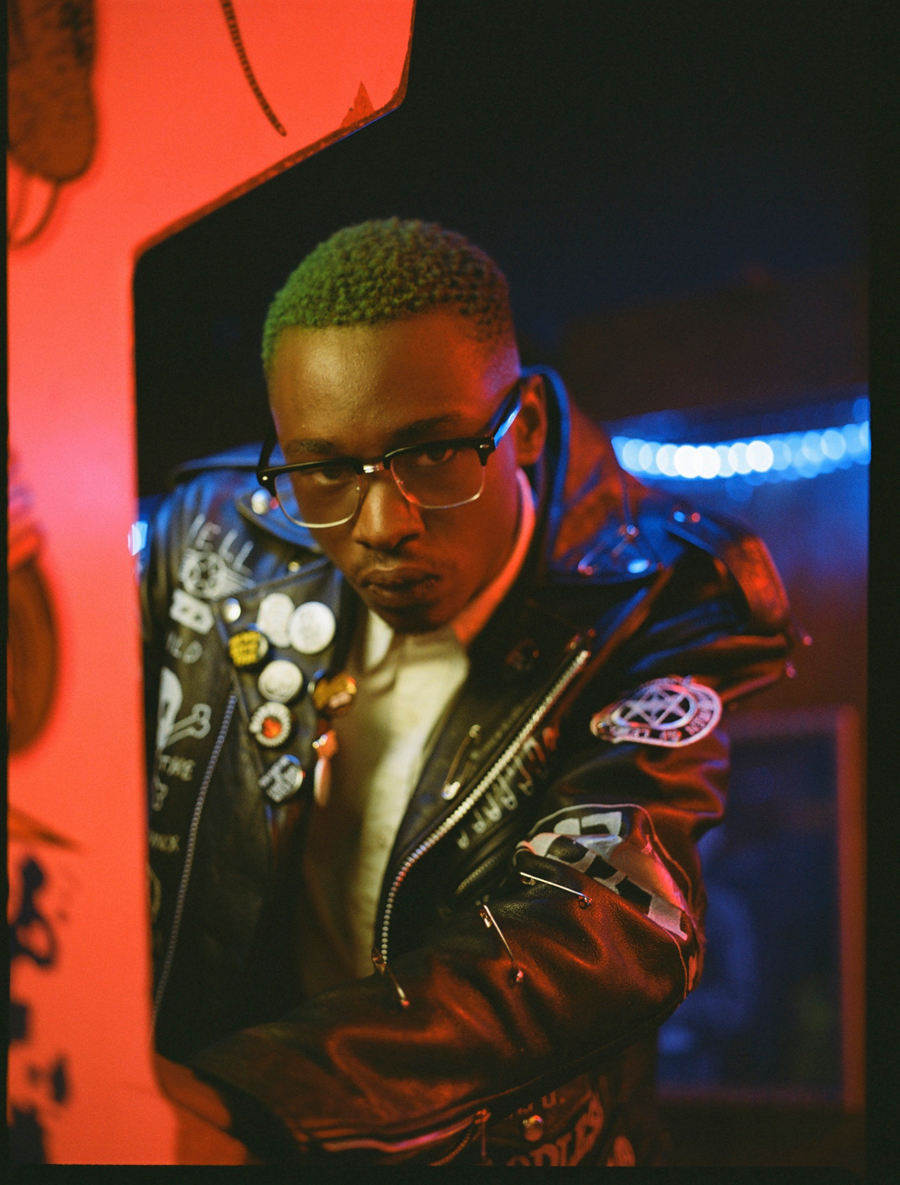

This spring, the visual artist Rashid Johnson will make his directorial debut with a film adaptation of Richard Wright’s 1940 classic novel Native Son. This represents a departure for Johnson. He is celebrated as an artist with an expansive conceptual and material breadth yet has never worked in narrative cinema. Successful as a photographer, printmaker, painter, sculptor and installation artist, yellow shea butter and black soap are Johnson’s calling cards: materials immediately recognizable to many people of African descent. You can buy them in plastic carry-out tubs at corner stores in Black neighbourhoods for US$5 a pound and stow them behind the bathroom mirror. Johnson puts them everywhere: he makes busts and paintings of them, covers tiles with melted blackness, or splatters the yellow butter oozing across a wood panel. The items – which, he claims are, on some level, about ‘cleansing’ – have become so important to Johnson that they dictate his palette, which has been until recently remarkably consistent: black and yellow, black and yellow.

For Native Son, Johnson teamed up with the Pulitzer Prize-winning screenwriter Suzan-Lori Parks. The subtly brilliant Ashton Sanders, who starred in Moonlight (2016) plays the anti-hero Bigger Thomas, with Sanaa Lathan as his mother, Trudy Thomas. It is an undeniably talented cast and crew, but Native Son is not an easy text to work with. Although it almost immediately sealed Wright’s fate as canonical in American letters, on its release the novel was criticized for its portrayal of Black characters. In particular, Bigger is a young man filled with hate who fights with his friends, curses his mother, rapes his girlfriend and murders both her and his boss’s daughter. Throughout the book readers are reminded that Bigger’s aggression stems from the absence of a future he must constantly face, an absence created by white supremacy. ‘He knew that the moment he allowed what his life meant to enter fully into his consciousness he would either kill himself or someone else.’ Perhaps anticipating the backlash to come, Wright announced within two weeks of the book’s publication: ‘I don’t know if Native Son is a good book or a bad book… and I really don’t care.’

To be sure, Johnson, Parks and Sanders have made Bigger infinitely more likeable, focused and worldly. Whereas in Wright’s version Bigger often festers in his own ignorance, in the film (set in the present day) he reads Paul Beatty, Ralph Ellison and Claudia Rankine. He listens to the music of Bad Brains and Death (two all-Black punk bands from former chocolate cities) – but also Beethoven, suggesting an alterity that he is actively interested in investigating. Bigger’s girl Bessie (played by Kiki Lane) is more fleshed out, and her fate far less determined than in the novel. The white folks are more developed, too – Jan (played by Nick Robinson) is less innocent in Johnson’s version and Mary’s (Margaret Qualley) interactions with Bigger have a complexity absent in the novel.

But the question remains, why would Johnson and Parks choose to remake this story in the first place? Early in his career Johnson had a solo show titled ‘Sharpening My Oyster Knife’ at the Kunstmuseum Magdeburg in Germany. The title was drawn from Zora Neale Hurston’s essay ‘How It Feels to Be Colored Me’ (1928): ‘I am not tragically colored … No, I do not weep at the world – I am too busy sharpening my oyster knife.’ In an article published in The New York Times on 24 February 2015, the writer Ayana Mathis discussed Wright’s novel and observed: ‘I don’t imagine many black people would have embraced such a grotesque portrait of themselves.’ How do we trace Johnson’s journey from sharpening oyster knives to grotesque self-portraits? After all, we are in the era of Jordan Peele (Get Out, 2017 and Us, 2019), and Oscar-nominated James Baldwin adaptations (If Beale Street Could Talk, 2018) and Love is the Message, the Message is Death (2016), the seven-minute psychic disturbance by Arthur Jafa which has become a global tear-inducing sensation. How are we to locate 2019’s Native Son within this filmic landscape?

When considering where we are as a people – Black people, American people, the people of late capitalism, surveillance capitalism, whatever – I often reflect on E.J. Hill’s installation of a high school running track, Excellentia, Mollitia, Victoria (2018) last summer at ‘Made in L.A.’ at the Hammer Museum. At the centre of the work was a podium Altar (for victors past, present, and future) (2018). Hill stood on it for three months, eight hours a day. He did not relieve himself, did not sit down, did not collapse. The longer you stood in front of him, the more you realized that he could only carry out such a performance by traveling deep inside himself. Altar was in many ways an activation of the other side of Peele’s ‘sunken place’ – like watching a man travel into a dark interiority not by hypnosis but by his own volition, in search of safety and sustainability. Hill’s performance was undeniably vulnerable and yet utterly impenetrable and when I think of blackness I often think of Altar.

Thinking of blackness as a deeply complex thing whose richness is protected and obscured from the larger white feels like a way into Native Son. Every Black character’s inner turmoil is painfully wrought in both Wright’s version and Johnson’s. And it’s worth noting where Parks stays sometimes uncomfortably true to the original text. Throughout Wright’s novel Mrs. Dalton’s blindness stands in for un-sight – a refusal to see the truth of race and class. Parks keeps that anachronism, despite the fact that it’s not generally acceptable to use blindness as a metaphor for ignorance in 2019. Perhaps she felt that one of Native Son’s most lasting marks is that it revealed what to white people had seemed perpetually oblique: namely, blackness. Perhaps she and Johnson felt that work is still necessary even in the era of Peele’s horror films and Baldwin tributes.

Baldwin drew a damning line between Native Son and Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852): ‘This makes material for a pamphlet but is hardly enough for a novel’ he wrote in his essay ‘Everybody’s Protest Novel’ in the Partisan Review, 16 June 1949. Watching Johnson’s film, I kept wondering how different it might be if it were transposed into a medium the artist is more familiar with. I imagined a series of still images or installations: of the small dining room where the family’s breakfast is interrupted by a giant rat; or the two Black boys walking in front of the big screen at theatre; the hair salon where the girlfriend works and where we see Bigger escape coolly out the back. The film is full of images of beautiful struggle, blackness and its tensions.

In the film’s details a journey through the last century of struggle through creative expression both normalizes that creativity and points to its diversity: Rachael Romero’s anti-apartheid woodcut on the wall of the mother’s room; works by Glenn Ligon and Rashid Johnson in Mr. Dalton’s office; Amy Sherald paintings in the Daltons’s sitting room. The film opens with Bigger placing his pistol on top of a school book, which in turn is on top of a copy of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (1952) on his bed, just before a closeup of his bejewelled chocolate-brown hands slathering yellow shea butter. Through these brief but salient pinpoints in racialized art history, Johnson locates a radical creative legacy that primarily resides in domestic spaces.

One of Parks’s much needed enhancements to the original text is to more fully realize the female characters. But Parks also brings her history of writing from a complex Black woman’s standpoint to her characterization of Bigger. In the hands of Parks and Johnson, Bigger may even be a queer figure, in Cathy Cohen’s left-politicized meaning of the term. In her 1997 essay ‘Punks, Bulldaggers, and Welfare-Queens: The Radical Potential of Queer Politics?’ Cohen contends that the politicization of queer identity had not properly accounted for the multi-marginalized non-queer identified person and did not take into consideration the ways queer marginality is always relational. Cohen argues for an expansion of a queer politic which aligns itself with a ‘marginal relationship to dominant power’– a necessarily destabilizing presence in the face of power.

At times – for example, when his sense of his ‘authentic’ Black masculinity is questioned by friends at the pool hall – Bigger easily steps into the archetype of Bold and Angry Young Black Man. This is the Bigger audiences will remember from Wright’s novel: frightened, enraged. At other moments – softer moments of solitude, as when he reclines in his room listening to cassettes, surrounded by literature and poetry – Bigger’s performative-self stretches into further reaching galaxies where race, class and gender are in a trio with improvisational solos, silences, harmonies and discords. For example, when Bigger sits to wait for Mr. Dalton, alone for the first time in a wealthy white man’s home, the first image he faces is Glenn Ligon’s Malcolm X (version 1) #1 (2000). Ligon, a queer Black artist whose work challenges normalized ‘Black’ iconography, consistently evades its own categorization by jumping form and style. Why place Bigger face to face with the clownish Malcolm X – in Mr. Dalton’s home no less?

Thinking of Bigger this way – as a dynamic dialogue between the multiple standpoints he occupies, circling around and through Black Manhood and its failures – may help us re-imagine Wright’s Native Son as a text with queer implications: intersectional, politicized, destabilizing. In many ways, Wright’s work made career/lives such as Baldwin’s and even Johnson’s possible: it revealed normalized ‘Black Manhood’ as failure, as irrevocably bothered by and bothering hegemony. In her contemporary consideration of Baldwin’s response to Wright for the New York Times, Ayana Mathis said that: ‘Whether the book […] fails as a work of literature is a question unworthy of a groundbreaking work that continues to inspire debate 75 years after its publication.’ We might watch Johnson’s attempt to revive the story with the same consideration – for its flaws, there’s something indelible in this story, something that continues to disturb.

Native Son will be released by HBO films on 6 April.

Main image: Rashid Johnson, Native Son, 2019, film still. Courtesy: HBO/Matthew Libatique