Reading Between the Lines of Christopher Wool’s Eloquent Paintings

‘A painting was actually telling me to fuck off. Gnarr. A little aggro retinal music’

‘A painting was actually telling me to fuck off. Gnarr. A little aggro retinal music’

1) Where He Works & What He Looks Like Christopher Wool is a lean, handsome, mocha-coloured Caucasian. He stands a little under six feet tall and works in two studios on the fifth and sixth floors of a brick building (one floor a working room, the other a contemplation zone) in the lower right-hand corner of Manhattan, between Avenue B and C, across the street from Figlia & Sons, Inc., Air Conditioning Specialists, also dubbed ‘Dr Cool’s Clinic’. His studio is shouting distance from the 9th precinct police station, which is a five-minute walk from Tompkins Square Park, a cheerful chunk of grass, stone and iron railings, known decades ago for its needles, melees and states of siege but now host to a multitude of adorable activities, including costume contests for dogs brave enough to wear tiny pillbox hats. Mr Wool possesses a noteworthy head. His hair is grey or steel-coloured, cropped to approximately half an inch, velvety like lead filings and magnetized around the crown or dome in a cerebral swirl. His demeanour is gentle, mild, recessive, with an undertow of nerves. The flesh on his face is dark and smooth like oiled oak, eyes gentle, lips thick. In the centre of the Wool face there is a spectacular nose, a nose that belongs on the page of Roman ideals. A seriously tremendous nose, something a rock climber would gaze at in awe, especially if it were on the scale of Mount Rushmore. How would one begin to climb it?

2) Over There With their hands inside white gloves Mr Wool and his assistant comb through a stack of gigantic silk screens on a table, select one, and then the two fellows carefully lift the large fragile paper over to an expansive wall, both men reaching up high to hang. After five or six were on the wall we sat a good 30 feet away from the pictures, our chairs angled towards the windows that looked out over the roof of Figlia & Sons. I was a little nervous, and I did not know Mr Wool well enough to suggest moving our chairs closer to the pictures for a point-blank dialogue. He seemed relieved by the distance. The art, as Anthony Perkins would say to Janet Leigh about the bathroom in Psycho (1960), is over there, if we wanted it, needed it, and I couldn’t help furtively looking over my shoulder, away from Mr Wool and our spirited conversation about rock climbing and skiing, at the monumental rectangles he made, all grey, black and white with their silky sheen and deft touch. The pictures’ loose correspondence with sheer rock faces and overhanging ledges, with knots and crags, was evident, as though their author, who was clad in similar dark and light greys, had been crawling all over the surface, corner to corner, diagramming routes up, across and back to the middle, to the coveted heart. They were theatrical, neurotic and playful, all washy and muted with vertical and horizontal smears, buzzy and energetic; private, giddy, conversant, subtle poems authored by a methodical New York psyche, someone who enjoys doing the same thing over and over and over again, searching for miracles in subtle variations.

3) Nativity & Mr K Christopher Wool was born in Boston in 1955, but he likes to say he was born in Chicago, ‘because that’s where I grew up’. His wife, Charline von Heyl, is a painter who shows with Friedrich Petzel and Gisela Capitain. His mother is a psychiatrist, and his father is a professor of microbiology. He has a brother who practises law. In another room, where office assistants laboured away on computers, there were a series of photographs by Martin Kippenberger mounted on the wall. One of them is of a Kippenberger lookalike, buck naked, with his arm around a naked woman, his equine-sized dong out and about, on a stroll. Mr Wool and Mr Kippenberger seem like polar opposites: K’s social antics, for example, versus W’s quiet, understated demeanour. I was curious about Mr Wool’s take on Kippenberger, and when I inquired, Mr Wool responded thus: ‘It was impossible to cross paths with Kippenberger and not be impressed by his power ... we weren’t close friends but I think he was genuinely interested in other people ... he wanted to be the centre of attention not because he was monomaniacal but because he thought it important to entertain ... like it was a part of his work ... he once said that he didn’t care to be remembered as a great artist but rather as someone who had made for good times ... of course he made incredibly inventive art as well ... in the end he’ll be remembered for both.’ What did Mr Wool have in common aesthetically with Mr Kippenberger? K, who dipped ferociously and unpredictably into all media all the time at a hectic pace, and W, who stays with a project for years, respecting the slow brew, gathering evidence carefully, solving a problem methodically. What might Mr Wool have learnt from an artist so different from himself? ‘One of the things that always impressed me with Kippenberger’s work was how he could bring his sense of the absurd or comic to almost everything he touched ... it’s very difficult to make a really funny abstract painting ... or an Absurdist abstract painting ... many have tried but few succeeded ... this is not necessarily what I’m doing but he, like many great artists, really broadened what could be done ...’

4) Where The Paintings Send Me Mr Wool’s paintings spark JSPR JHNS thoughts. Specifically, they call to mind Johns’ clever, sneaky word paintings from the late 1960s and his ever-present compulsion toward self-quotation. RBT RSCHBG’s De Kooning erasure is also evoked (totally different from W’s self-cancellations and mark removals, but still, erasure and removal are in the mechanically reproduced air, especially when Wool silk-screens his marks only to obliterate them). Mr Wool has a nostalgic soul, which helps him reanimate Jackson Pollock’s drips via mad loopy sprays of black and, on a rare occasion, red. Roy Lichtenstein’s pastiche of action painting’s earnest brushstrokes lurks, as does photography’s dot pattern, silk-screen traces, frames within frames, repeated gestures and many Warholian touches pulsing, tricking out Wool’s pictures. The multiple levels of mediation and process are pushed to acute powers (many untitled silk-screen ink on paper works from 2007 – marks scanned, collaged, rephotographed, printed – are difficult to identify, is this part of the plan?). There is the mystery of how they were made (close inspection will get you nowhere) and a greater mystery of what they might mean. His thin, transparent, black and white stains evoke the graininess of old cinema – like Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves (1948) retooled abstractly into Woman on a Bicycle (2003) – as well as a history of stainers and squigglers from Arshile Gorky to Joan Mitchell to Wassily Kandinsky. There are many things to see inside his abstractions, and the mind takes this opportunity to drift, to go gently berserk. During an interview discussing Howl (1955) Allen Ginsberg confessed: ‘My intention was to make a picture of the mind, mistakes and all.’ Mr Wool’s twisted, coat-hanger lines bunch up, tangle, echo and mock each other, dimming and brightening, dripping like loose, torn-apart, black Freon tubes or coils, and seem very much to reflect the contortions of the mind in action, flickers of cognition. At other times his paintings focus on something atmospheric (several untitled enamel or silk-screen ink-on-linen pieces from 2005), like air, sky, the special insides (What’s The Time?, 2005), the gunk, the stomach, bowels, crime scene details (Little Birds Have Fast Hearts and Minor Mishap, both 2001, and You Said Tomorrow Yesterday II, 2005), the blotchy ebb and flow of caprice (She Smiles for the Camera I, 2005). The author of these paintings favours titles that reveal nothing, à la the ubiquitous Untitled. Or he goes for cryptic, arresting, playful, flirty titles that tease and fan the theatrical flame – leading viewers in the direction of figures or characters or scenes of some sort. Or he leads us toward the anatomical: Loose Booty, Double Party Booty and Double Booty Party are a trio of 1999 paintings that feature clusters of looping ovals that at times look like ass cheeks, ass cleavages, cracks and oval skid marks.

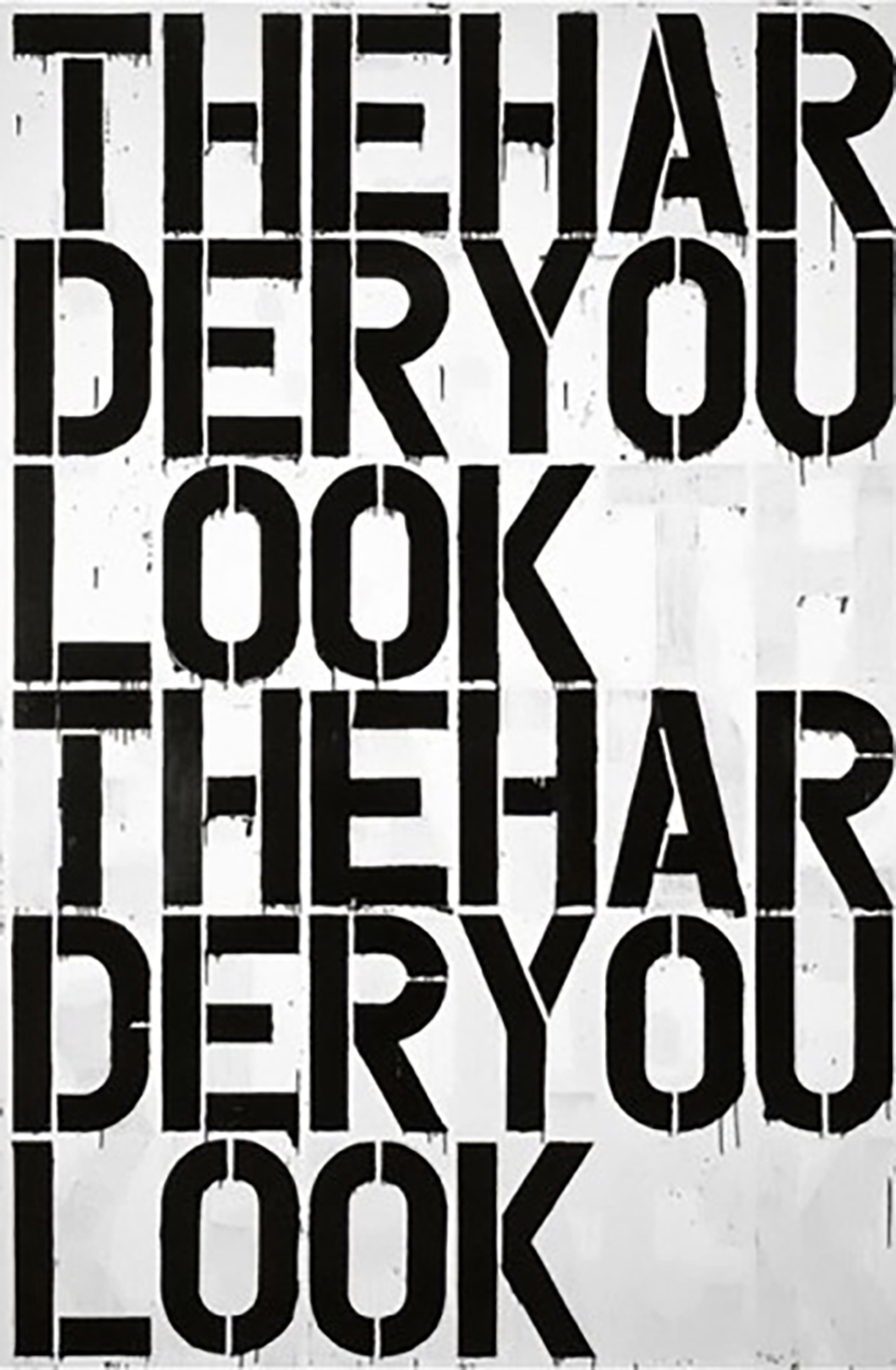

5) Reckless Reading And then a late, untitled comic word painting from 2000, rears its head and pulls me out of my woolly delirium, THEHARDERYOULOOKTHEHARDERYOULOOK. Mr Wool’s abstractions really do have a powerful psychic prompt, as though the paintings have eyes you can’t see, fixed at dreaming distance but also focused on something very close. When queried about the way in which his work can seem at once abstract and figurative, Mr Wool responded: ‘Yes ... more literal than figurative to use your words ... but afraid to go too far with this because it’s so easily misunderstood ... publicly I would probably insist on labelling the work abstract ... but for me they are “pictures” with all that that implies ... and that often means that “things” are pictured ... but things can be psychological or sensed or dramatic as well as just a figure in a landscape.’ It’s also curious to think about a painter who has gone to great lengths to avoid the brush. Most of his gestures seem to be made via sprays, rollers and rags. The rag wipes and blunt interruptions of line have a formal, Hans Hofmann-y precision: vertical bands or wipes in harmonious combative league with their horizontal counterparts, both erasing and establishing their own presence, and then an occasional emotive mark of panicked desperation, and Mr Wool has turned this into a delicate part of his vocabulary, an elliptical grammar, as though his own touch embraces and is quite amused by the perversion of itself.

6) A Different Kind of Pretty At times there’s actually something wilfully ugly about Wool’s paintings (which recalls a line by W.S. Merwin: ‘Gradually Mr Jameson took to smiling at me in a peculiar draggled way like an ugly girl from under an umbrella.’). In some paintings there’s nearly an aesthetics of blight, random splatters, leering discharges, whitewashes, erasures, dismissals – like paintings made with cleaning fluids in which the arcs the solvents avoided are visible. But all his avoidances and self-cancellations build up into a graceful, anarchistic cacophony of notations, expressive gestures. Mr Wool is present in the work whether he likes it or not, and I think he does like it, or it’s fine by him, as long as his presence splinters the picture plane and disrupts the reader’s smooth, perfect day. ‘When we stand before another human,’ Franz Kafka wrote, ‘we stand before the gates of hell.’ In the mid-1990s Mr Wool painted some very large, cheerfully morbid, black-splattered daisies that appeared to be growing from a faecal patch (East Broadway Run Down, 1999); daisies fortified by sun reflected off an oil derrick. These paintings lean more toward scatology than sunshine and contain the oddest mix of the elegant, the sexy and the beautiful – albeit beauty arrived at via refuse, a regal rectology if you will, something virtuously repellent, miraculously subtle, solemn, mystical. Rarely is there a thick surface in a Wool painting, an overworked area.

7) Look Mum, No Hyphens I have to admit that I was one of those people who yanked their hair out when initially confronted with a room of Mr Wool’s word paintings. The word series began in 1987 and continued into the early 21st century. At the time, 1990, I thought they were smug, flip, arrogant, simplistic; another art world gimmick straight from bogus island. Perhaps I took my orthography and punctuation a little too personally. Perhaps I simply couldn’t handle his blurring of words, his language alterations and his snapping words right down the middle, no hyphens. I cursed those snot-nosed paintings (brats). I wanted to vandalize them. The paintings and I, we were not getting along. And then one painting turned to me and said, ‘ANDIFYOUCANTTAKEAJOKEYOUCANGETTHEFUCKOUTOFMYHOUSE’. A painting was actually telling me to fuck off. Gnarr. A little aggro retinal music. Ah, but to hate is to love, so the soothsayers occasionally prophesy. The paintings’ comic seed was in me. Years passed, and the humorous ghosts inside Mr Wool’s cryptic utterances suddenly made sense to me and turned me into an ardent admirer. I started to see the words as figuration, enlarging English letters to the size of a human torso, sometimes bigger. I understood them in terms of a body. So much dimension in their flatness. They had that anxious object thing going on in them, as Harold Rosenberg would say. They made more and more sense. They also prefigure the broken syntax of text messaging by at least a decade. Now when I see the word paintings, those stark agitators, I slap the ground in banana excitement (as chimpanzee expert Jane Goodall would say). I slap the ground even harder when I see his paintings. They are miraculous. Mr Wool, the devout abstractionist. The paintings are seductive, and it’s OK if at some point the painting laughs at you for falling for it so deeply. But such laughter is not at the viewer’s expense any more. It’s more of a conspiratorial laugh.