Embarrassment of Riches

In her prints, paintings, photographs and videos, Andrea Büttner explores poverty, community and her philosophy of 'little works'

In her prints, paintings, photographs and videos, Andrea Büttner explores poverty, community and her philosophy of 'little works'

‘Beauty is an object’s form of purposiveness as it is perceived in the object without the presentation of a purpose.’1 Thus Immanuel Kant, in The Critique of the Power of Judgment (1790), attempts to delimit the scope of the beautiful and runs straight away into vexing counter-examples – works of art not least among them. What are we to do, he wonders in a footnote, with the stone artefacts often discovered in ancient burial mounds? They look like tools, so have a purpose, but that purpose remains unknown. Are they not, then, beautiful? Not in the philosopher’s nascent theory of beauty: ‘We have no direct liking whatever for their intuition.’2 A tulip, on the other hand, we consider beautiful, ‘because in our perception of it we encounter a certain purposiveness that, given how we are judging the flower, we do not refer to any purpose whatever’3.

Tulips and stone axes are just the start; empirical examples proliferate in The Critique of the Power of Judgment, and they have a habit of working against the purpose of Kant’s own text, which is to prove the pure and disinterested nature of beauty. Consider, for instance, his reflections on mere charm (as opposed to real beauty), which is frequently to be found superadded to the object: charm arrives in the degraded form of decoration. In painting, sculpture and architecture, ornament is secondary to design – we should not mistake the charms of a gilt frame, nor even the pigments in the painting itself, for the beauty of form or composition. That would be, Kant writes, as if we paid more attention to the spirals and curlicues of Maori tattoos than to the proportions of the faces on which they appear.

Enlightenment exoticizing aside – New Zealand and Australia had lately furnished European writers with new images for ‘primitive’ otherness – such examples are always curious, even embarrassing, in a work of philosophy: a discipline that tends to forget or deny its literary dependence on imagery and anecdote. In Kant, these moments actually resemble those secondary charms that he would like to banish from the realm of the beautiful. But a critique of aesthetic judgment can hardly do without actual objects; they decorate Kant’s writing like so many jewels, they grow on it like mosses.

What would happen if you took literally Kant’s rhetorical illustrations and turned them into pictures? That is precisely what Andrea Büttner has done in Images in Kant’s Critique of the Power Judgment (2014): a set of eleven large prints on which images culled from diverse sources, including Kant’s own library, purport to illustrate his text. (The piece, accompanied by an illustrated edition of Kant’s treatise, was first shown in Büttner’s solo show at Museum Ludwig, Cologne, in 2014. It is currently featured in the British Art Show 8.) So, the tattooed Maori is therein an 18th-century engraving, the tulip in a botanical illustration, the stone tool in a photograph of a museum artefact. There are the statues and paintings one might expect to accompany Kant’s discussion of the beautiful, the classical ruins and erupting volcano that go with his reflections on the sublime. But the illustrative project has overshot, absurdly, its avowed end because here, too, are anonymous gardens, 18th-century women in their finery, geometric forms that just happen to have been mentioned in the Critique, even examples of Büttner’s own work. Anything at all that suggests an image has been translated into graphic, painted, drawn or photographed form. And, while there is an echo of the encyclopedia, the effect is also to cut the philosopher’s abstractions down to size, to collapse aesthetics into the everyday, the mundane, the image-dump of Google searches and Wikipedia.

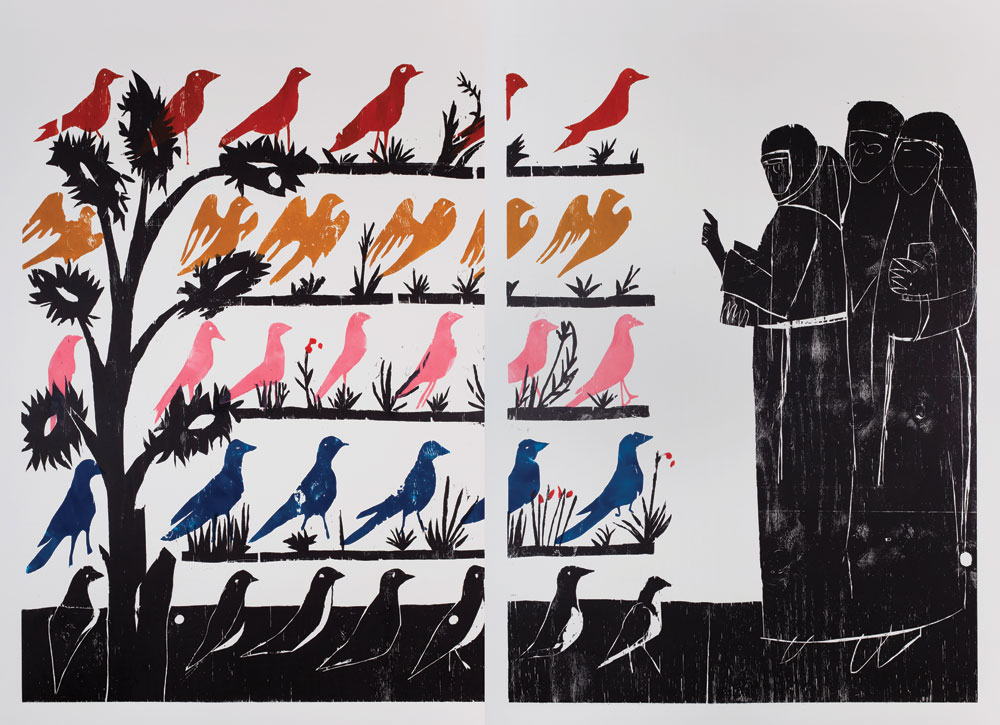

The literal-minded but learned comedy of Images in Kant’s Critique of the Power of Judgment is of a piece with the simultaneously high and low concerns of Büttner’s earlier work. The Stuttgart-born artist, who currently divides her time between Frankfurt and London, has made work in a flummoxing array of registers and media. She is perhaps best-known for her woodcuts, but also produces prints and etchings, paintings on glass, photographs and videos, raw canvas paintings whose fabric brings to mind uniforms and monastic habits. Her recent ‘Phone Etchings’ (2015) are coloured renderings of the smears and greasy blurs that sully pristine mobile-phone screens. Büttner’s sculptures include gobbets of unfired clay, apples piled in gallery corners, museum-style benches made of plastic crates and planks of wood. What all of this work has in common, and in common with the Kant piece, is a consistent urge to impoverish or, rather, to reveal the wealth in poverty, the dignity in shame and embarrassment, the conceptual richness hidden in the empirical. There’s a clue to the lowering if not lowly ambitions of Büttner’s art in a text-only woodcut from 2005, which baldly states: ‘I want to let the work fall down.’ Büttner turned to the woodcut in the 1990s, when, as she once noted, it seemed a decidedly ‘uncool’ medium, too bound-up with the inheritance of artists such as Georg Baselitz. Now, she says: ‘I like having one area where I can be physically engaged, working with an angle grinder.’ But woodcuts are also apt expressions of an abiding aesthetic and conceptual strand in Büttner’s work: a medievalism that has seen her engage not only her own experience of growing up Catholic, but a complex of historical and contemporary ideas about wealth and poverty, shame and dignity, the relationship of art to one’s form of life. The most obvious example in this regard is her 2010 woodcut Vogelpredigt (Sermon to the Birds), in which the 12th-century Italian friar St Francis of Assisi speaks to a parliament of birds.

Büttner's sculptures have a consistent urge to impoverish or, rather, to reveal the conceptual richness hidden in the empirical.

St Francis has been a key figure for Büttner: a theological and art-historical nexus for her interests in poverty, community and the concept of work or, more precisely, what she terms her ‘little works’. Francis, the son of a wealthy cloth merchant, famously abjured familial riches and initiated a rule among his followers: ‘to live in obedience, in chastity and without property’. As Giorgio Agamben puts it, in an account of their monastic precepts, the Franciscans’ aim was ‘not some new exegesis of the holy text, but its pure and simple identification with life, as if they did not want to read and interpret the Gospel, but only live it’.4 According to Agamben, Francis and his friars imagined an entirely new attitude and relation to things: a simplex usus, by which use and property rights were separated and all was held in common. (Francis had underestimated the Church’s attachment to the idea of property; a century after his death, Pope John XXII issued an edict disallowing the Franciscans’ pious communism.)

From this historically distant and ideologically fraught context, Büttner has extracted the idea of ‘little works’. As she put it in an interview with Nikolaus Hirsch and Hans Ulrich Obrist in 2013: ‘For me, it’s about exploring the poetics of “letting fall”, of addressing issues such as: how much do you want to show off?’5 Frequently, the answer to this question has been not at all, especially in those projects where Büttner has worked with religious communities of women. In 2006, she began drawing the nuns of a Carmelite convent in Notting Hill, London, and the following year she equipped them with a video camera so they could record their own modest labours. Little Works (2007) shows the women making baskets, bowls, crucifixes, satchels, drawings and icons of the Virgin Mary. According to one of the nuns, Sister Luke, this annual burst of industry involves ‘everyone taking an interest in what everyone else has done’; the labour involved, and the finished objects, are both solitary and collective, instances of a rigorous but joyous form of being-together.

There are nuns elsewhere in Büttner’s work. For another video, Little Sisters: Lunapark Ostia (2012), she filmed women from the Little Sisters of Jesus who are based at an amusement arcade outside Rome. ‘We are people of the spectacle,’ declares one of them to camera. In an earlier sound piece, Corita Reading (2006), Büttner invoked the pop-art activist Sister Corita Kent, whose sloganeering serigraphs borrowed their language from theology, pop music and the avant-garde. Kent – who eventually left her order, the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, in 1968 – is another instance of an artist whose work is hardly separated from the mundane, from life itself. Büttner seems to be drawn to these figures, and whole communities, who conspicuously carry on a labour, worship or practice that is determinedly minor.

Among the unexpected links made in Büttner’s work is that between the idea or practice of ‘little works’ and, at some apparent remove, a quite recondite field in botany. Between 2011 and 2014, she pursued research at National Museum Wales, Cardiff, among its renowned and extensive collection of mosses. These lowly plants, which do not flower, were classified by Carl Linnaeus as reproducing asexually, by ‘hidden marriages’: they seemed to have been ‘excluded by the creator from the theory of stamens’.6 A secretive and modest sort of plant, then, but also a ubiquitous one. Büttner’s research led to ‘Hidden Marriage’, an exhibition at the museum in 2014. The mosses remind her of the dust flourishing on Marcel Duchamp’s Large Glass (1915–23), photographed by Man Ray as Dust Breeding in 1920. A degraded but transformative stuff, in other words. In German, moss is a slang term for money: ‘Ohne Moos, nix los!’ (Nothing happens without moss.)

There is a scatological and scurrilous impulse in some of the work that is entirely appropriate to Büttner's concerns with povery, shame and encouraging the work to 'fall over'.

Büttner’s Cardiff show also included works by Gwen John – an artist once quite overshadowed by her brother Augustus – whose drawings and paintings accord with Büttner’s attachment to ‘little works’ and a certain Catholic context. (In 1911, John moved to the Paris suburb of Meudon, where she repeatedly drew nuns and other worshippers at her local church.) Büttner’s reference to a historically rescued or retrieved artist like John is part of a pattern of engagement in her work with ‘minor’ artists and neglected forms. The first work of art she recalls seeing was a large woodcut by HAP Grieshaber, installed in the secretary’s office at her convent school. (Grieshaber had taught the nuns to make woodcuts.) In 1982, Grieshaber showed his work at a school for teenagers with learning difficulties. Büttner appropriated photographs of the students viewing the exhibition for her own HAP Grieshaber/Franz Fühmann: Engel der Geschichte 25: Engel der Behinderten (HAP Grieshaber/Franz Fühmann: Angel of History 25: Angel of the Disabled, 2010). The faces, she says, remind her of people painted by Hans Holbein the Younger and his contemporaries in the 16th century.

The historical citations have continued in Büttner’s more recent work. Piano Destructions (2014) is a video installation that repurposes the documentary history of mostly male artists (Joseph Beuys, Nam June Paik, Ben Vautier) attacking pianos: an avant-garde gesture that is also an (inadvertent) assault on the gendered history of the instrument. Büttner’s ‘Piano’ woodcuts (2013–15) involve dismantling a piano and using its parts as printing blocks: an altogether more modest and meticulous sort of violence.

Neither Büttner’s art-historical references nor her theological interests ought to suggest that hers is a polite or constrained practice. There is a scatological and scurrilous impulse in some of the work that is entirely appropriate to her concerns with poverty, shame and encouraging the work to ‘fall over’. In partial homage to the plain, dun-hued garb of the Franciscans, Büttner has painted gallery walls brown as high as she could reach, creating, as she puts it, a ‘shit space’ for her art to inhabit. At times, she makes the link between shit and riches comically clear: ATM (2011) is a photograph of a cash-machine keypad smeared with an unknown brown substance: it might be food or it might be faeces. Diamantenstuhl (Diamond Chair, 2011) is a plain white Monobloc chair – Büttner has photographed many of these – on which rests a small brown nugget; it is actually a rough diamond, but it sits on the pristine white plastic of the chair as if to say: one of us is pure and, therefore, beautiful, but neither is going to tell.

- Immanuel Kant, The Critique of the Power of Judgment, trans. Werner S. Pluhar, Hackett, Indianapolis, 1987, p. 84

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Giorgio Agamben, The Highest Poverty: Monastic Rules and Form-of-Life, trans. Adam Kotsko, Stanford University Press, 2013, p. 94

- Nikolaus Hirsch and Hans Ulrich Obrist, ‘Interview with Andrea Büttner’, in Andrea Büttner, Koenig Books, London, 2013, p. 274

- Carl Linnaeus, Systema Naturae, trans. M.S.J. Engel-Ledeboer and H. Engel, B. de Graaf, Nieuwkoop, 1964, p. 24

Andrea Büttner is an artist based in London, UK, and Frankfurt, Germany. This year, her solo exhibitions have included Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, USA, and Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Germany. Her show ‘Beggars and iPhones’ opens at Kunsthalle Vienna, Austria, on 8 June. Her work is also included in the British Art Show 8, in Norwich, UK, (24 June–4 September) and Southampton, UK, (8 October–14 January 2017).