Real, but Not Quite: VR at the 58th Venice Biennale

From Marina Abramović to extinct tropical birds, seeing more than what’s there

From Marina Abramović to extinct tropical birds, seeing more than what’s there

Everyone is missing the point of ‘interesting’. The title of the 2019 Venice Biennale points us not to whatever meaning the titular adjective holds, but rather to the particular history of the phrase it’s embedded in – an ersatz Chinese curse which, through use in rhetoric for over a century, has nevertheless acquired the status of truth. Ralph Rugoff’s choice of title pinpoints (or tries to) the unpredictable, uncanny afterlife of ideas, caught in an endlessly reinforcing circuit between imagination and instrumentation, fiction and authority, real and unreal.

In an alternate reality, this conceptual terrain would be charted by performance, role-playing or drag – though (perhaps outside of the performance programme that took place over the opening days) gender is one thing Rugoff’s show feels pointedly uninterested in. Instead, the ‘uncertain artefact’ (as he described the titular curse in his curatorial statement) is manifested in rather concrete, aesthetic objects: barely-there artworks, flickering half-things, hyper-produced and immaterial, from Tavares Strachan’s ambient, glowing skeleton, suspended in a dark room in the Arsenale (Robert, 2018), to Cyprien Gaillard’s L’Ange du foyer (Vierte Fassung) (Fireside Angel, Fourth Edition, 2019), a projection via holographic LED-display of a billowing animation after Max Ernst’s L’Ange ou Foyer (1937).

Real, but not quite: virtual, then. Bang in the centre of the Arsenale’s gloomy procession was a permanent queue for Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster’s commission Endodrome (2019), the artist’s first VR work, a collaboration with HTC Vive Arts. The experience takes place in a monochrome room, five participants seated, séance-like, around a marble table – visible to those outside via a window into the room – each donning an HTC Vive headset. Beginning in gloom, the view is gradually filled with shifting clouds of pulsing colour, somewhere between thermal imaging and ink marbling, like the vision of a Victorian opium-eater. The work’s gothic flavour is enhanced by the key interactive element – if you twist your head, puffs of black seem to shoot across the space according to your direction of view, swooping about like Dementors in the Harry Potter films (or, I thought, the Spray Can tool in the first version of Paint). Because of the predetermined sitting position, it was hard to know how fully to explore such physical interactivity. At one point, some ectoplasmic form emerged right from the front of my field of vision, possibly in line with my breathing, possibly just by coincidence; either way, it was probably the closest I’ll ever come to blowing my nose with a jellyfish.

A good eight minutes or so long, the sumptuous visual field which the piece offered was of a limited delight: I could have done with a character or, I hazard, a story, to carry me through. Where the work excelled, I thought, was in its spatial presentation. Having completed the experience, I went back to peer at the next wave of participants through the window: all seated and neatly sealed in their elegant, sombre space. From the outside, you’d never guess the psychedelic visions they were enjoying from the outside. Which is, on some level, how it always is with art.

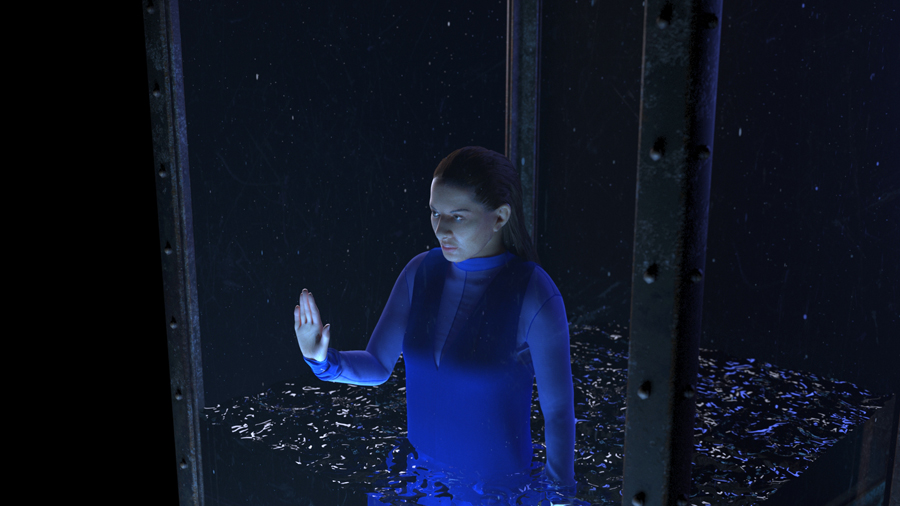

If Gonzalez-Foerster’s piece dramatized the disjunct between external observation and subjective experience, Marina Abramović’s collaboration with Acute Art, presented with the Phi Center in the Ca’ Rezzonico, sought to leverage sensory encounter in aid of the most urgent collective action problem of our times: climate change. Rising takes the viewer face to face with a polar ice cliff, lit with son et lumière intensity by flashes of lighting, turning the ice green and violet. Bookended by roaming a dank industrial space, which put me in mind of my favourite arcade game, ‘House of the Dead 4’, the artist herself finally appeared at the work’s close, like a dreaded end-of-level boss. Trapped in a glass tank filled with water, Abramović’s fists banged against the panes, though her face, as I recall, remained impassive. I later read that viewers could lower the level of water in the tank by pledging to save the environment – a big commitment I managed somehow to miss, but one which positions the artist’s presence as the nexus of human goodness and global survival. At the start of the work, after desolate facts about global temperature and glacier melt, the Talmud was quoted, to the effect that to save one life is to save the whole world. For all the visual flair and good intentions, there was an abject grandiosity present that might incline some less charitable viewers to let this particular avatar drown.

It’s either surprising or entirely fitting that many of the works deploying sophisticated technology across and beyond the biennale concerned themselves with the crisis which began with the technological advances of the Industrial Revolution. Jakob Steensen’s Re-Animated (2018), in the Future Generation Art Prize exhibition presented by the Pinchuk Foundation, conjured the ghost of the Kauai’O’o, a tropical bird not observed since 1985, and presumed extinct. Alongside a video narrating the history of the ornithological survey and slaughter, donning one of four VR headsets plunged the viewer from tree-height to jungle floor in the rainforest, where a passing flock of translucent birds fly towards an amorphous shape, hovering mid-air, emitting haunting sounds – the last recording made of the bird’s call, in 1987.

Slowly morphing coloured blobs and spores spread across a huge, high-definition LED screen, providing a miasmic backdrop to Florence Peake and Eve Stainton’s performance Apparition, Apparition (2019) in the Teatro Piccolo Arsenale. Positioned as ‘a dig […] within the frame of ecological devastation,’ Peake and Stainton’s semi-nude, wordless dance – full of movements that felt like metaphors for mutual dependence and interconnection – was a more abstract treatment of climatic collapse, but no less affecting or invigorating for it. Back in the Arsenale proper, Hito Steyerl’s show-stopping This Is the Future (2019), a multiscreen installation replete with elevated viewing platforms and walkways bathed in a fog of dry ice, depicts renderings of mutant plant life, swelling and heaving as if climatically-adapting in real time. The most prominent screen featured a deadpan commentary on the paradoxes of civilization’s technological telos: ‘100% of humans will die’, intones the voiceover, as images of a drowned Venice, data centres and Stonehenge flash by. ‘We are predicting the future with old data’. This last phrase could have almost served as a caption for the nearby installation of Ed Atkins’ Old Food (2019), in which the Wunderkind of digital animation imagines a world of folksy, faux-medieval toil, all lamplight, wizened crones and Breughelian frenzy, accompanied by racks dense with costumes borrowed from the Teatro Regio in Turin. Fresh ingredients, old flavours.

Evoking vanished or vanishing things – times, species, landscapes – many of these works played to VR’s fundamental facility for conjuring the appearance of what’s not there. Was Indrė Šerpytytė’s beautiful Territorial Symphonies (2019), which evoked nations without representation in the Giardini via their national anthems, played by a brass band on a boat sailing through the Rio dei Giardini – sufficiently intangible to count as ‘virtual’? (Commissioned by Block Universe and Alskeral, the performance was itself a kind of ghost or echo – of Ragnar Kjartansson’s brass-band carrying SS Hangover, which floated the waterways of the Arsenale in 2013.) The most bracing and ballsy work I witnessed all week took a different tack entirely. Commissioned by the Nordic Art Association (NKF) with curator Jonatan Habib Engqvist, the VR Pavilion was a working barge departing from a tiny Marxist social club on a corner of the Fondamente de la Tana. Participants donned Oculus Rift headsets and came aboard to experience Venetian artist Sara Tirelli’s Medusa (2019), which takes place within an anonymous, white cube gallery space. Soundbites began to play, relaying news and regulations relating to unaccompanied migrant minors arriving in Sweden. The viewpoint switched to a high, isolated platform in the middle of the gallery, up to which a cast of unidentified male youths, all wearing baggy sportswear, climbed via a steep ladder. One by one, each person came closer and then stood breathtakingly face-to-face with the viewer, smiling, smirking or (did I imagine it?) gritting teeth. Every time they did, I physically flinched. The viewpoint shifted again to hover above a group of conspicuously white people, all clad in uniform t-shirts, massed in the same collective pose of the survivors of the wreck of the Medusa, as depicted in Théodore Géricault’s iconic 1818–19 oil painting. The same youths from before lounged about the platform, removed, holding flares. Concerned, but not enough to do anything – like most of us.

When the VR video finished, ten minutes of the barge trip remained, sailing past yachts and collectors and critics and locals, their stares ranging from confusion to derision. Shivering in my lifejacket and blanket, I never felt so conspicuous, so foolish, so displaced. It was the most ‘immersive’ experience I’ve had all year.

Main image: Sara Tirelli, Medusa, VR Pavilion commissioned by The Nordic Art Association and curated by Jonatan Habib Engqvist, 2019. Courtesy: the artist; photograph: Cecilia Tirelli