Rediscovering Moki and Don Cherry’s Utopian Visions

‘Organic Music Societies’ shows the nomadic world the late American jazz icon and Swedish artist created for their friends, collaborators and children, Neneh and Eagle Eye Cherry

‘Organic Music Societies’ shows the nomadic world the late American jazz icon and Swedish artist created for their friends, collaborators and children, Neneh and Eagle Eye Cherry

‘On nights before our days of travel, the sewing machine’s drive was a lullaby,’ writes musician Neneh Cherry, reflecting on her mother, the artist Moki Cherry, in a new book about her life and work with her husband, the free jazz trumpeter Don Cherry. Moki would stitch stage sets and costumes into the early hours. ‘She even made the luggage,’ Neneh adds.

While Don is recognized as one of the most important musicians of his generation, Moki’s broad artistic output – tapestries, costumes, set design, poetry, sculpture and collage – has been less documented. The new book accompanies an exhibition of the same name, ‘Organic Music Societies’, curated by Moki’s granddaughter Naima Karlsson and Lawrence Kumpf and Adrian Rew of New York’s Blank Forms, which shines a light on their collaborative work for the first time.

United by a dedication to ‘improvizing on stage and in living’, as Moki described it in her diaries, she and Don turned their nomadic lives into the embodiment of artistic and spiritual practice. Based in Tågarp in rural Sweden, they transformed an old schoolhouse into a home for their family and a theatre for their work. Neneh calls it ‘the mothership, our family headquarters, the source’ – a space to host a milieu of artists and develop a radical way of living, closer to nature and loosed from the commercial, discriminatory trappings of the New York jazz scene.

‘I think it’s quite easy to assume that Don Cherry was already this interesting jazz musician and that Moki just joined his world,’ Naima explains, instead positioning Moki’s input as fundamental to the creative universe they established together.

A trained designer, Moki sidelined her professional aspirations in the mid-1960s to live a more free-wheeling life with Don and their children, Neneh and Eagle-Eye. Textiles allowed her to make a virtue of this necessity.

‘For traveling, fabric was a great, practical solution,’ Moki writes. ‘Roll it up, put it in a couple of duffel bags. Go on tour with the family and musicians in a minivan.’ On early flyers drawn by Moki, audience members were invited to bring their own carpets to create 'an environment/atmosphere, the stage being the home and the audience part of it’. Don echoed its radical potential: ‘If there’s anything that’s going to happen in society, it must start in the home.’

As such, the world they named ‘Organic Music’ blurred the lines between art and life – and for Moki, creative and domestic work was often indistinguishable. On camping trips that doubled as musical tours, Moki recalls making dukiburgers – vegetarian sandwiches of adzuki bean patties – for the kids. She was ‘always cooking, sometimes under absurd circumstances,’ but relished the challenge of creating this world on her own terms.

In 1971, Don and Moki were invited to bring their home to Modern Museet’s ‘Utopias & Visions 1871–1981’ exhibition in Stockholm, where the family lived for almost three months inside a geodesic dome dressed in Moki’s fabrics. A caravan of musicians passed through to jam with Don in what was an audacious confluence of art and life.

In this setting, the function of Moki’s work was integral to its meaning. Taken on their own, her appliqué pieces are a riot of colour and expression, draped on walls, furniture and above the doors of the spaces they inhabited. In some of the photos from Tågarp, it is hard to see where the work ends and the home begins. Taken as a whole, it’s clear that the distinction is irrelevant.

As well as an artist in her own right, Moki was also a voracious researcher, whose fascination with the spiritual and artistic traditions of East Asia, India and Tibet found its foil in Don’s own ‘Collage Music’, which knitted together sonic influences from around the world.

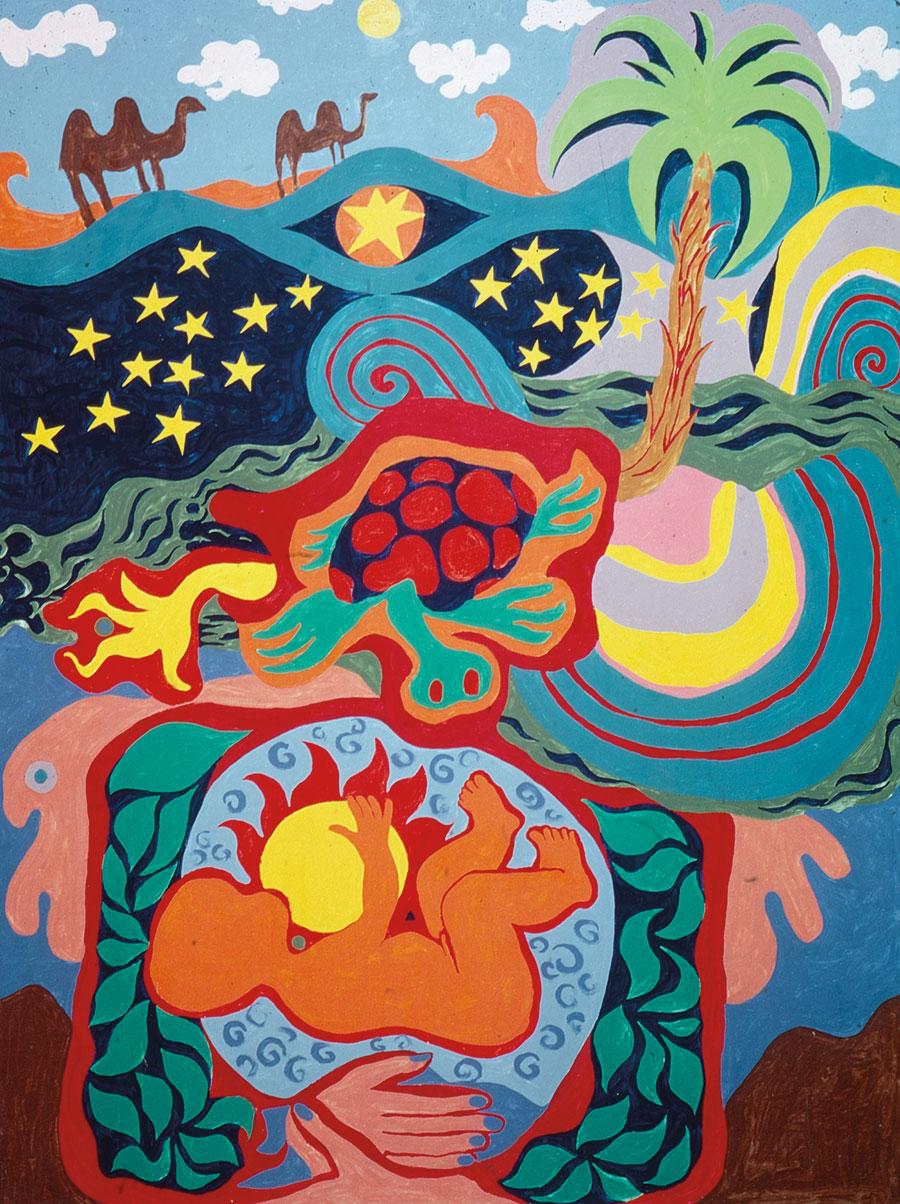

Acknowledged as a pivotal album in his oeuvre, Don’s 1973 album Organic Music Society is perhaps the most complete artefact of their collaborative work. It is adorned in Moki’s flowing artwork – a tableau reflecting the assemblage of the music, which draws on Indian ragas, Brazilian ceremonial hymns and contemporary minimalism alike. It features Moki playing the tambura, her instrument of choice, which – like the sewing machine – provided the drone, or sustain, to the group’s collective improvization. ‘Sometimes you can forget that that drone in there, because it just goes on and on,’ Naima reflects. ‘But it holds it all together.’

Moki Cherry passed away at the age of 66, largely overlooked by an art world she once described as being better suited to entrepreneurs than members of the community. For those who experienced the Tågarp she built, her legacy is as much in the act of living and making as in the objects themselves. ‘Moki is everywhere and in everything,’ Neneh concludes. ‘Art is life, so we carry on. I guess this is how she lives on.’

‘Organic Music Societies’ is currently on show at Blank Forms, New York.

Main image: Workshop at Tågarp Schoolhouse, ca. 1974. Left to right: Åge Delbanco(Babaji), Naná Vasconcelos, Don Cherry and Eagle-Eye Cherry. Courtesy: Naima Karlsson and Blank Forms, New York