Rediscovering the Overlooked Talent of French Sculptor Camille Claudel

With 11 of her works on show at the Musée d'Orsay, one of the most underrated artists in modern European history is brought out from the shadows

With 11 of her works on show at the Musée d'Orsay, one of the most underrated artists in modern European history is brought out from the shadows

Along the second floor of the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, 11 sculptures in plaster, terracotta and bronze trace the career of one of the most underrated artists in modern European history. Until 11 February, these newly acquired works by Camille Claudel (1864–1943) – historically best known as the lover and artistic partner of Auguste Rodin – will be on show before entering the Musée d'Orsay's permanent collection; the rest will be going to five other museums throughout France, including the Rodin Museum in Paris and the recently opened Camille Claudel Museum, an hour southeast of the capital; the Sainte-Croix Museum in Poitiers; and the Piscine Museum and the Camille and Paul Claudel House, both in the north.

Initially, none of these sculptures were expected to be made public at all. Last year, the Claudel family consigned 20 lots to Artcurial, a Paris-based auction house, which put the works up for auction in November. However, with the backing of the French Minister of Culture, Françoise Nyssen, the government used a relatively rare law created in 1921 allowing them to 'pre-empt' works of 'national importance' that are to be sold through auction houses in France. As is law, the government matched the sale price, including buyer's premium, and purchased the sculptures for France's public museums.

In the case of Claudel, the public should be particularly grateful. These sculptures range from works made during her beginnings as an art student in Paris in 1881 until just before she was committed to a psychiatric hospital, most probably against her will, in 1913.

One of the clearest themes throughout these works is Claudel's interest in old bodies and old age, especially the ways in which elderly women are treated, depicted and understood. Her stunning Old Woman's Head (c.1890), which will go into the Musée d'Orsay's permanent collection, portrays an octogenarian Italian woman, Maria Caira, who also modelled for Rodin. Made entirely of plaster, Claudel's sculpture details Caira's sunken eyes, oversized ears, bulbous nose and wrinkled face with the same respect and careful detail as she applied to one of her first and youngest creations, Diana (c.1881) which depicts the young face of the Roman huntress, raised on a plaster pedestal with her features styled as if she were a head of state or queen. In doing so – and thanks to the museum's decision to immediately juxtapose the two – Claudel draws attention not so much to Caira's age and her according features but more to her power and dignity. Rodin praised these sculptures as full of 'pathetic realism'.

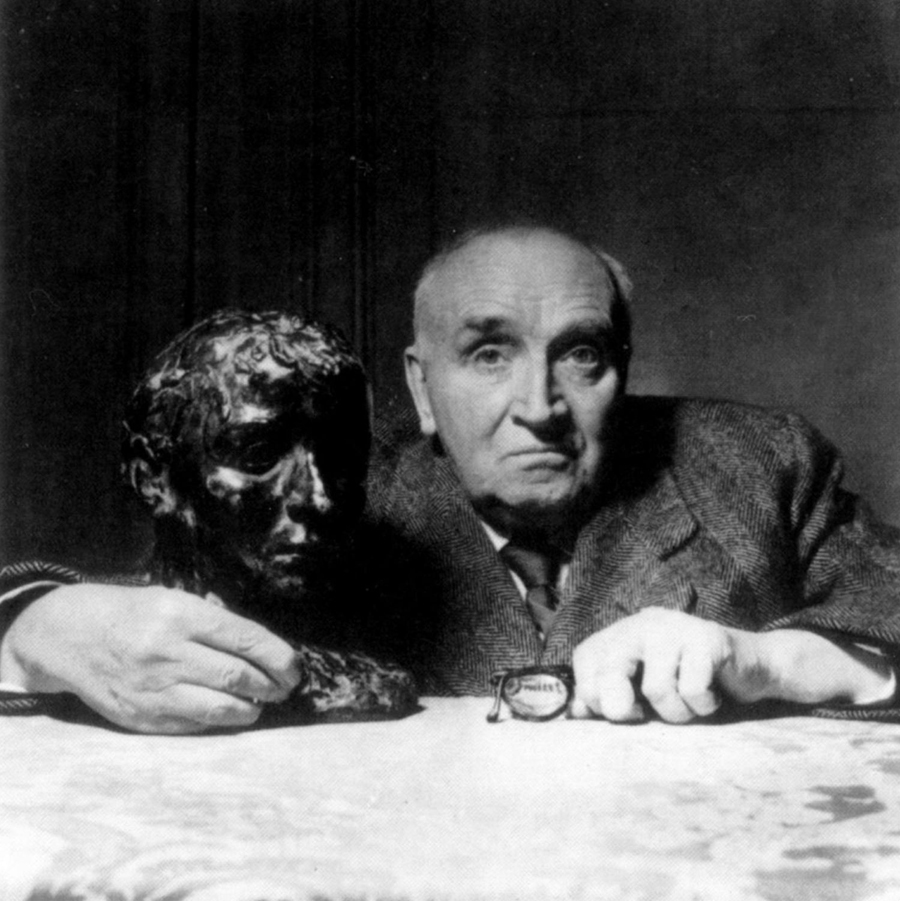

In 1881, when Claudel was 17, she moved to the Montparnasse neighbourhood of Paris with her mother, brother and younger sister, leaving her father in northern France, where he worked as a financier. Claudel matriculated at the Colarossi Academy, studying under the sculptor Alfred Boucher. When Boucher moved to Florence, he hired Rodin to teach his class. Claudel began working directly with Rodin, often in his workshop. In her early 20s, she modelled for him and learned from him. However, Claudel was no Véra Nabokov: she largely worked with the older artist, not for him and quickly established her own artistic style.

After roughly eight years of work and romance with Rodin, she created one of her most political sculptures, Woman at Her Toilette, or Woman Reading a Letter (c.1895–97), also on show. A delicate, intricate rendering of female domesticity, Claudel places a large plaster drapery over the scene, effectively turning it into a theatre set. In doing so, she draws attention to the performative nature of this feminine ideal. Her decision to abort her child with Rodin in 1892 both ended their relationship and inspired her interest in this kind of feminine faux-perfection.

In 1913, Claudel's father died. Her mother didn't tell her and Claudel only found out weeks after the fact. Later that year, she was committed to a psychiatric hospital in Ville-Évrard, an eastern Parisian suburb. Curiously, she did not sign her own admission papers; her brother, Paul, and a doctor did. Her mother also forbade the institution from giving her mail that came from anyone but herself and Paul. Her family was controlling her by committing her to the psychiatric hospital, according to Ruth Butler's Rodin: The Shape of Genius (1993) and Elizabeth Kerri Mahon's Scandalous Women (2011). Claudel's brother was jealous of her talent and the support she'd always had from her father; her mother never approved of her choosing the artist's path or her romance with Rodin.

In 1943, she died in a psychiatric institution outside Avignon, having been moved from the hospital outside of Paris due to the advancement of German troops. Eight years after her death, Paul organized an exhibition to display her sculptures at the Rodin Museum. Privately, however, he still didn't respect her art. 'My sister Camille had an extraordinary beauty, moreover, an energy, an imagination, a quite exceptional passion,' he said shortly after the exhibit. 'All these superb gifts came to nothing: after an extremely painful life, it ended in complete failure.' Her now-public works show how wrong he was.

Camille Claudel’s work, presented in Galerie Françoise Cachin, level 2, is on view at the Musée d'Orsay, Paris, France until 11 February.