Art Rules!

Rita McBride explains her ten-point manifesto for the Dusseldorf Art Academy

Rita McBride explains her ten-point manifesto for the Dusseldorf Art Academy

Jan Kedves When you gave your inaugural speech as the new rector of the Dusseldorf Art Academy last October, you presented a ten-point manifesto. Why did you choose that format?

Rita McBride You know, even though my German has become quite good since I joined the academy as a professor in 2003, it’s not wonderful, and listening to me read out four pages in German is basically intolerable. So for my inaugural speech, I wanted to find a way to communicate something in a shorter form. I re-read a book of manifestos I have at home, mainly by architects and architectural movements. I found the format extremely powerful in terms of attitude and clarity. And I liked the radical optimism most of these manifestos express.

JK So you wanted to convey a ‘radical optimism’ about studying art now and making art in the future?

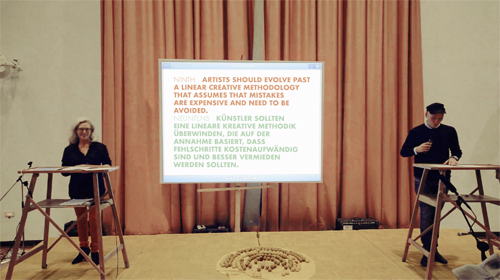

RB First of all, I wanted to signal that something’s changing here at the academy. That’s why I didn’t just read the manifesto, in fact it was a performance. The inauguration speeches I’ve seen since I joined the academy have been quite stiff. They were held in the mornings, the students were seated, the rector would read his speech and then the professors would leave together for lunch, without the students. It was quite segregated. For my performance, I decided to change the structure of the room: I took away the stage and seats and had everyone standing. And it was in the evening, so we could all eat together and have a party afterwards. I made a visual slideshow which had the manifesto in English and German in a special typography designed by an ex-student of the academy. And I had a translator who was also an ex-student. So I was just as much concerned with performance as with what was being said. And it worked well. There was a lot of energy in the room, there was clapping, cheering, a real kind of enthusiasm, which made me extremely happy.

JK In the first point of the manifesto, you stress the importance of the ‘we’ over the ‘I’ …

RB Yes, I was thinking about how artists can be a productive part of society in the future. For me, it’s about trying to get away from isolation, from the understanding of the artist as a separate entity – the artist as genius. I’m not one of those people who believe that a momentof inspiration can only happen when you wait for it, away from society. I think it’s a myth. Today, information is exchanged so freely it’s amazing. With social networking, people are sharing so much information and so many thoughts all the time – how could artists isolate themselves from it?

JK You’re thinking about a kind of online art made via crowdsourcing?

RB That’s not at all what I’m suggesting. Nobody knows exactly what art making will be in the future. All I’m saying is: we can’t ignore the changes the internet brings; they’re already here in a very powerful way. In preparing the manifesto I read a lot of texts about the internet and it was a great opportunity to try and understand where we are now. I was born in 1960 so obviously there’s a lot of years between the students’ ages and my own, and there’s been a shift in how they process and share information. Actually, thinking about the internet led me to another idea in the manifesto which is about being able to take apart your tools. Not just to use tools, but to understand what they really are.

JK In the manifesto you quote from the Maker’s Bill of Rights to Accessible, Extensive and Repairable Hardware published in Makezine in 2005: ‘if you can’t open it, you don’t own it.’ The phrase was subsequently adopted by copyright activist and co-editor of the blog Boing Boing Cory Doctorow.

RB Actually, I first came across this phrase in New York as I was walking though the Chelsea Market. One store with a huge glass window that I could look through had all kinds of tools for shaping wood – for furniture, chair legs and so on – and it was full of people working with them. I was fascinated by this workshop in a commercial setting. At the back of the store was a banner that had the phrase ‘If you can’t open it, you don’t own it’, and right below: ‘Maker Faire’. It is a movement driven by a desire to understand how to make and remake things, instead of throwing them out.

JK So Maker Faire is part of the whole ‘craftivism’ craze?

RB Yes, it’s a bit too romantic for my taste, but I’m not against it at all. The phrase could mean that you should be able to open your mobile phone and understand the mechanisms in it. Or it could mean that, in a wider sense, we as artists should try to understand the institutions we’re in. Or that we shouldn’t ignore the structural aspects of our societies that determine our place within them.

JK The second point of your manifesto states: ‘artists shall make things rather than buy things’, and the third says: ‘artists consider technology as a fundamental given.’ Should artists who work with technology build their own tools? For example should a photographer working with Photoshop programme his own image processing software, instead of using an off-the-shelf product?

RB Nobody has to, but I would hope that some of us would like to. It could have an enormous effect. Coming up with combinations of different programmes, trying to force them into new sets of possibilities – these things have always been done in art. Photographers make their own cameras to get exactly what they need, and painters mix their own colours.

JK Does that maybe warrant introducing a course in programming at the academy?

RB Not really, that would be too territorial. Instead of adding a new discipline I’d actually like to workless in a defined class system and instead have the departments in the academy communicate more with each other. A lot of people here don’t know what each other is doing – doors are kind of closed. We could be enjoying more exchange and cross-information. This will be a focus of mine as the new rector. Relatedly a really nice thing happened recently: I received an email from a wonderful student from Peter Doig’s painting class, his name is Piet. He knows quite a lot about programming, and he offered to run a course for hisfellow students. So next term Piet is going to share what he knows about coding and programming. This kind of initiative is far more interesting to me than appointing a new professor for programming.

JK As an artist who works mainly with sculpture, how do you think today’s digital image culture changes the relationship of students – who experience a lot of art through Google Images – towards physical space?

RB That’s a difficult question, but there really does seem to have been a change. For example, last term my class was working on a group show and a lot of the students made very elaborate, amazing, three-dimensional objects. But when we went to install the show – in a bank, actually – the students pushed everything to the walls. Even though the physical reality of their objects was very prominent, they didn’t put any space behind them. You could hardly walk around them. It seemed as if they wanted people to look at the works as images.

JK Was there a light-bulb moment when you pointed this out to them?

RB Totally. And a lot of nervous giggling.

Rita McBride is a sculptor born in Des Moines, Iowa. She lives in Dusseldorf. In August 2013 she became rector of the Dusseldorf Art Academy, taking over from Tony Cragg.