Rindon Johnson on the Currency of Not Knowing

Ahead of his latest solo show at Chisenhale Gallery, the artist speaks to Nicholas Nauman about working with animal byproducts and getting comfortable with failure

Ahead of his latest solo show at Chisenhale Gallery, the artist speaks to Nicholas Nauman about working with animal byproducts and getting comfortable with failure

Nicholas Nauman: How does your new show, ‘Law of Large Numbers: Our Selves’, at Chisenhale Gallery in London differ from its previous iteration, earlier this year, ‘Law of Large Numbers: Our Bodies’, at SculptureCenter, New York?

Rindon Johnson: Since the show crossed the Atlantic we lost some works; there’s three left. The first one you encounter in London is the book, The Law of Large Numbers: Black Sonic Abyss [2021]. It traces my thoughts, my theoretical helpers and my pandemic reformations.

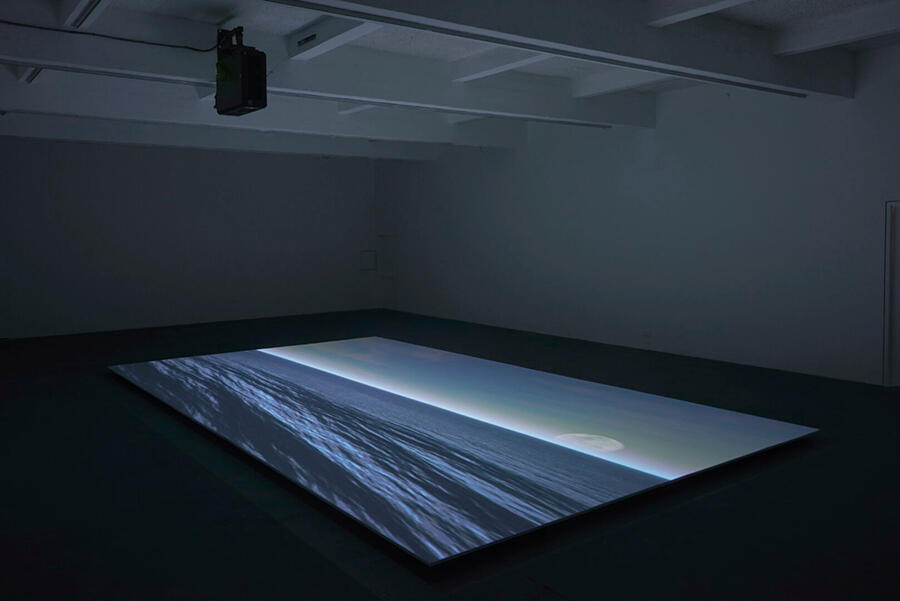

Then you open the door and enter the gallery to Coeval Proposition #2: Last Year’s Atlantic, or You look really good, you look like you pretended like nothing ever happened, or a Weakening [2020], a CGI work which will live at Chisenhale as a 9-metre-long projection floating about 11 centimetres from the floor. The piece uses data from 2020 to re-render in real time (second for second) the fluctuations of the North Atlantic ‘cold blob’ – an area of the ocean where the temperature is dropping while surrounding waters are getting warmer; it's also the geographical midpoint between the New York and London shows. The cold blob is slowing down the Gulf Stream, and we don’t really know what that means. Weather patterns will change drastically, it will affect fish supplies, it will affect everything. My projection is almost half the width of an Olympic-size pool. It feels like you can swim in it. This work is my first data-flirtation piece. I sourced the data and remade an entire year. It's a work of abstraction but its image is figurative. It is 366 days long – 2020 was a leap year.

The last work, Coeval Proposition #1: Tear down so as to make flat with the Ground or The *Trans America Building DISMANTLE EVERYTHING [2021] is to be installed outside on a pontoon behind Chisenhale Gallery, so you can only see it from the other side of the canal.

NN: At SculptureCenter, I was struck by your decision to install Coeval Proposition #1 – which reconfigures the iconic skyscraper from your hometown of San Francisco into a monumental pun about your trans identity and its entanglement with race, life and death – in proximity to your oval cowhide piece, A Round, Solid figure, it has occurred to me that I exercise to make myself cheaper for my insurance company, I mean for myself, Anthem, noun a song of loyalty or devotion, sung antiphonally, sung recited or played, the sung sun asunder, alternatively, the sun sung asunder, is this now, stand by yourself then, in or into a separate place, Solid figure, we’re up all night, it has occurred to me that I exercise to make myself cheaper for my insurance company, I mean for myself, Anthem, we decided a group of us, a noun a song of loyalty or devotion, sung antiphonally, sung recited or played, the sung sun asunder, alternatively, the sun sung asunder, is this now, stand by yourself then, in or into a separate place, Solid figure can we go to the woods now? Let’s stay out of all things together, apart. [2018–ongoing]. The former is made from smoothly finished reclaimed California redwood. It has huge, sharp angles that reference the architecture of the original structure, while the latter is a much smaller, curvy piece of organic matter that looks like it might have evolved out of the wall. There’s something playful yet deadly that resonates between them.

RJ: The TransAm is a running joke, mostly with myself. I’m a Trans American and that’s my building, it has my name. The deeper I dove, the more sinister the building became; that pyramid, a holy shape, was designed at the request of Transamerica CEO, John Beckett, to bring as much sunlight to the streets below – a sly metaphor for financial freedom: a beaming light shining down on the edifice from the heavens. The light is money; not so funny. A Round, Solid figure... also started out as fun. ‘I’ll try an oval,’ I thought, but then it quickly moved beyond my control. After I work on some pieces, I’m like: ‘We don’t need to be together anymore. You can go, live your fucking life.’ But there are others that just get inside of me. A Round, Solid figure… was one of the first works where I wasn’t sure what was happening. And not knowing, if I’m being grandiose, is the currency of being an artist. If I make such a blatant portal to not knowing, I have to keep it around. Three years on, I still don’t really understand this piece.

NN: What is it about that work in particular?

RJ: Something about its consistent resistance to holding its shape as an oval feels intrinsically out of hand to me. I talk about this in my book. The idea of continuity surfaces in this shape, and A Round, Solid figure… should be able to hold that continuity from certain vantage points, but it doesn’t. I know that I’ve tried to make an oval and I keep failing. That failure is also part of it. Like, another joke is that I’m trans, and to a particular discourse, far from me, I’m a failed man, and when I’m translated back to my own context, that makes me a better man. Like, ‘Haha who tries to be a man?’ Well, ‘me', I guess?

NN: How do you think about your body in terms of these cowhide works that you’ve gotten to know so intimately – touching them and observing them over long periods of time – versus cow by-products that are presented as food?

RJ: I have a lot of allergies, and I should really only eat meat and vegetables. This adds an extra charge to the work. There was this moment when I decided to be vegetarian but, because my body can’t handle plant-based proteins, I ended up giving myself an auto-immune disease. I’m learning to live with the fact that I’m always going to be a participant in destructive food systems, which means, to me, that I must be hypercritical, specifically if I’m not living my criticism of meat production all the way through. But I can’t, it’ll kill me.

For my opus, I want to purchase a cow and live with it through its entire life cycle. Cows can live between 30 and 40 years. Yet, typically, dairy cows are slaughtered by age ten. Soon, I’m going to go into the business of cow futures: people will buy a cow in order to get an artwork made from its hide 30 years later, when that cow eventually dies of natural causes. Of course, such a project raises all kinds of questions: will the cows live in squalor or luxury? Will they live with me or would I hire someone to take care of them? Will this operate like those sponsor-a-child charities and every month you’d get a photograph and update of your cow? It’s an odd way to spend a life: an allegory of a system that will likely not exist by the time the painting is done. But it seems necessary. Just because something changes form does not mean it stops cycling through our lives. The cow is our contemporary, we created them and they created us – that will never change. Anyway, I want to put my money where my mouth is.

Rindon Johnson’s ‘Law of Large Numbers: Our Selves’ is on view at Chisenhale Gallery, London, UK, until 6 February 2022.

Main image: Rindon Johnson, Coeval Proposition #2: Last Year’s Atlantic, or You look really good, you look like you pretended like nothing ever happened, or a Weakening, 2021, installation view, Chisenhale Gallery, London. Courtesy: the artist, Chisenhale Gallery, London and SculptureCenter, New York; photograph: Andy Keate