The Risk of Rejection: Two New Books by Kate Zambreno

Diana Hamilton reflects on the dual urges to be beautiful and well-reviewed – even when you want to reject both desires

Diana Hamilton reflects on the dual urges to be beautiful and well-reviewed – even when you want to reject both desires

Reading Screen Tests (2019), Kate Zambreno’s new collection of stories and essays, I was at first annoyed. Which is to say I felt implicated: as a writer, I did not want to be, like Zambreno, another ambivalent voice on the beauty of other writers – especially the beauty of women whose author photos are supposed to guarantee their prose styles – or to have to recognize the same predilections in myself. I did not want to develop a habit of writing with clarity about other writers’ opacity, for example, or of publishing texts about the longing for ephemerality that publishing itself prevents. I would put down the book, frustrated by the self-recognition produced by one essay, go to sleep, and wake up from a dream that would bear a striking similarity to one Zambreno describes in the next.

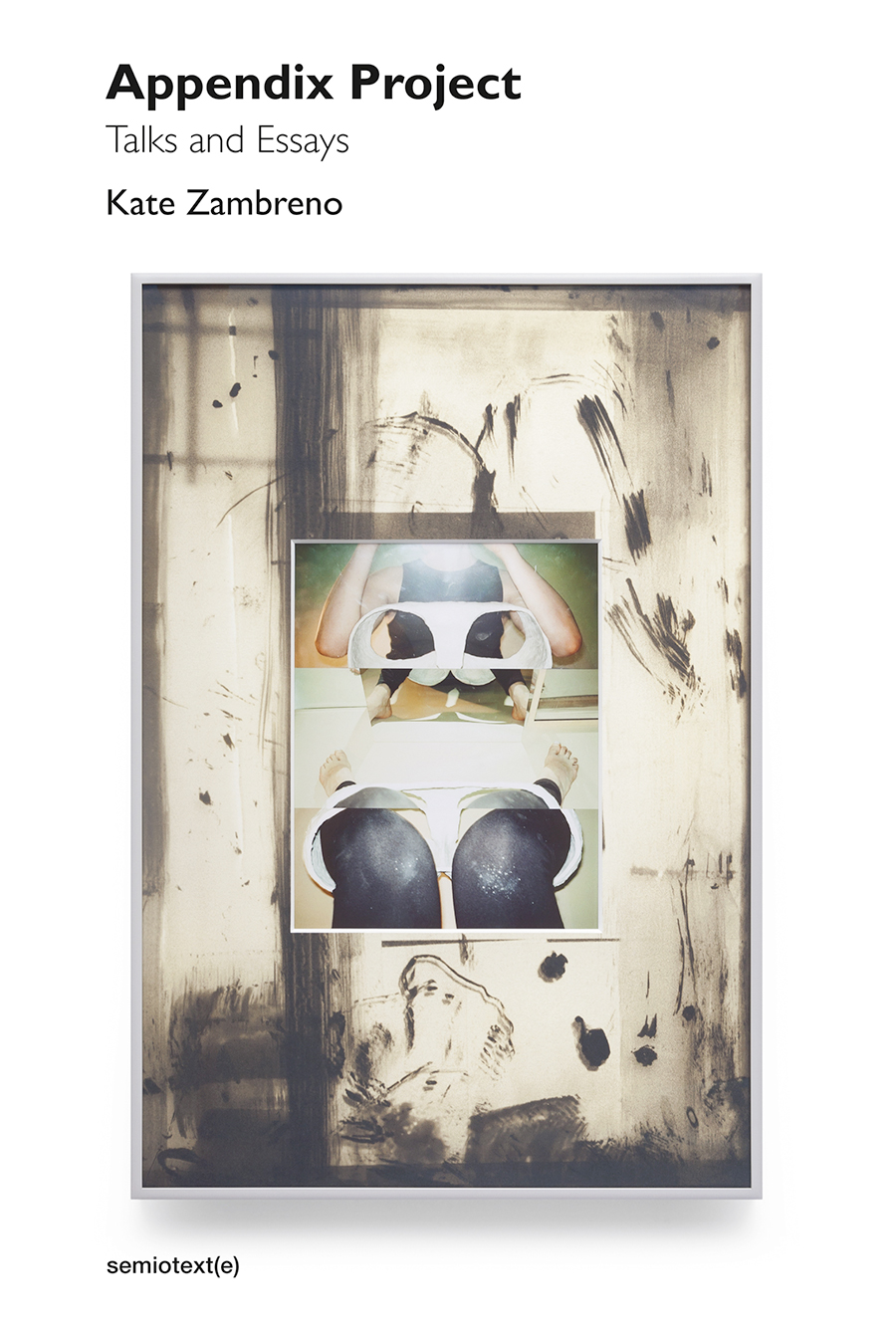

So, when I turned to Appendix Project: Talks and Essays (2019), Zambreno’s recent book of ‘appendices’ to her 2017 Book of Mutter (both from Semiotexte), I was relieved to read of the author’s correspondence with her friend, Sofia Samatar, about ‘the uncanniness of intertextuality’ – the way shared sensibilities often lead writers to generate identical mental Works Cited lists and habits. (It is as if reading Kathy Acker when you’re young makes you, too, grow up to write about Anne Collier’s appropriative photography, as Zambreno and I have both done.) What I was reacting against in Screen Tests – and what eventually led me to reread the book with pleasure and relief – was this feeling of the too-familiar: Freud’s unhappy reaction to ‘seeing these unexpected images of ourselves’ (when he mistakes his mirror image for a strange old man) as ‘a vestige of the archaic reaction to the “double” as something uncanny’.

She means ‘vestige’ in both senses. In Appendix D, ‘The Preparation of the Body’, she thinks through writing’s corporality, where the appendix is ‘seen as unnecessary or excessive.’ She admires books that maintain this vestigial quality, the impression that they are leftovers from some unfinished evolutionary process, drafts or ‘essays’ in the old-school sense of trials. She examines Bhanu Kapil’s writing on Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee (1982), noting that both Cha’s book and Khapil’s Ban en Banlieue (2015) ‘have the feeling of the manuscript, or the posthumous.’ In both of her new books, Zambreno reflects on the dual urges to make beloved objects and to be loved oneself – to be beautiful and well-reviewed – even when the aesthetic and political canons to which you respond reject both of these desires.

In a ‘screen test’ on (and at times addressed to) Acker, she searches for a word for ‘the parasitism of middlebrow art and literature that steals from interesting and radical art but in the process strips it of its ferality, its political urgency, its queerness, its threat.’ When she writes, in an essay loosely on David Markson’s experimental novel Wittgenstein’s Mistress (1988), that ‘this sort of heavily referential writing is difficult for readers, I’ve been told,’ she dryly refuses to participate in said parasitism by allowing her references to take control over her writing rather than letting the latter feed off the former. In Antoine Compagnon’s book on citationality, La seconde main (Second Hand, 1979; reissued 2016), he describes a quote as functioning like a transplanted organ: there’s a risk of it being rejected by the body of the citing text. For Zambreno, the risk is inverted. She doesn’t want her body to successfully assimilate a quote. Instead, constant and recurring references – to Warhol’s screen tests, Barbara Loden’s Wanda (1970), ‘layers and layers of appropriation’, Acker, et al. – are protective against the gross finality of cohesion.

Given its title, it’s not surprising that Screen Tests is also interested in fame. But I think the interest also betrays an affinity for shortcuts to meaning. The famous – especially actors whose heydays have passed, suicides or worse, people forced to outlive their names – don’t need character development. The characters of famous people precede the text, that is, and require no construction; Zambreno can rely on the implication that these are people someone already knows. And of course, readers are themselves characterized by what they do or don’t recognize.

I keep returning to a two-page story in Screen Tests, ‘Cinefile’, about a woman who was ‘obsessed with literature and film but couldn’t seem to find a way to make a life out of it.’ She turns to the narrator for recommendations of books to read and movies to watch; the narrator suggests Abbas Kiarostami’s Close-Up (1990), and proceeds to summarize its plot.

At this point, the titular cinefile is no longer the narrator’s interlocutor, but Hossain Sabzian, the film’s protagonist: ‘this film . . . encapsulated for me this longing to be near art, that the impersonator and the family all feel . . . but how shut out they felt from the possibility that they could live the life of an artist.’ Zambreno herself documents the quotidian nature of proximity to art. In Appendix Project, she offers a list of places she has fed her daughter: ‘I became used to taking my breast out in art spaces’. In ‘Cinefile,’ it is not clear whether the summary is for the reader’s sake or the woman’s, as the story ends ‘Had she watched it? Of course, she had.’ Perhaps this ending is meant to suggest that of course, you, too, the reader, have watched this movie, or have felt this desire to be in proximity to art, or have felt, even while living ‘the life of an artist,’ that such living was impossible.

Main image: Kate Zambreno, Screen Tests, 2019. Courtesy: HarperCollins