Rome Around Town

Various venues, Rome, Italy

Various venues, Rome, Italy

Parked outside Magazzino is an old electric-blue Ford Escort estate, a flashback to the mid-1970s. Formerly a relatively state-of-the-art enabler of human motion, Elisabetta Benassi’s car now looks asleep: its cargo area is full of black soil topped with a pair of bronze tortoise shells, and the work is titled – like the show as a whole – Letargo (2016), meaning ‘hibernation’ or ‘lethargy’. In a city as mired in the past as Rome, these might not seem like affirmative qualities. Yet, for this resident they seemingly are, not least against the insidious ideology of productivity. Inside the gallery sits another motionless wheeled device, a petrol-powered orange mower. This readymade, blazoned with the initials ‘M.B.’ for the maker, Meccanica Benassi, serves as an ironic portrait (via a shared name) of the artist as industrious worker. On a nearby wall is a cream-coloured metal panel gridded with holes, the type used in workshops to hang tools on: Benassi has festooned it with metal logos for cars mostly named after fast, free, agile animals (Jaguar, Cougar, Mustang), which here are as mobile as a metal tortoise shell with no tortoise in it.

Erupting from another wall is a thick metal tube. Continue into the next space and this turns out to be the ‘trunk’ of a painted-metal replica palm tree that, angled sideways, fills the room. The sort of device used, out in the world, to conceal telecom towers and antennas, in sculptural terms it’s a cool riot of overlapping steel fronds, looking like dark green starbursts. Hibernate, camouflage, down tools – Benassi’s work is visually acute and often authentically dreamlike, but its chief appeal might be the open-ended applicability of its punkish outlook.

Self-protection arises again in T293’s aggressively hip, seven-artist group show ‘Homo Mundus Minor’, where a coquettish balance of revealing and hiding is enacted through a gamut of media, outlooks and occasional wearisome flashbacks, such as Anna Uddenberg’s already over-familiar girls-riding-suitcases sculptures. Lucas Blalock’s photos look diaristic (beds, bodies, bags) but are invaded frequently enough by postproduction effects – ghostly pink overlays, collaging, colour tweaking – to scan as softly treacherous. Maggie Lee’s video Mommy (2015), filters a melancholy personal narrative (her parents’ separation, the loss of her mother) through a caffeinated rumpus of presentational modes, from home-movie footage to flashing captions to animations to a frenetic, discontinuous sound track, in which neither viewer nor artist seems able to reach the story’s core. Lui Shtini’s rigorously flickering little painting manages to look like a black bell, urinal, body, moustache and a few other things: a tiny heart-shaped aperture at its centre mulishly refuses to help out.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px Helvetica}

At Frutta, Gabriele de Santis continues constructing a sardonically bright world in which artists are figures of mass-cultural veneration. This time, he moves on from sports – ersatz basketball courts decorated with faked-up Ed Ruschas, locker rooms containing dangling football shirts for Alberto Burri, Piero Manzoni and Mario Merz – to fizzy graffiti. The gallery has been cutely bombed, floor to ceiling, with wraparound text in classic 1980s side-of-the-train style, though the subject matter, naturally, is niche. Facing the entrance is the legend ‘I can’t breakdance on a Carl Andre but I can climb a Donald Judd’. Flanking this (if I’ve interpreted the blocky lettering right) is the phrase ‘Throwback Thursdays’ – hashtag as graffiti tag – and reading left to right we end with a big green parrot, a sunny cipher of unoriginality. De Santis’s approach, it’s clear, is bulletproof, if tail-chasing. If his art is light, consumable and full of historical in-jokes, that’s also apparently his issue with the art world. Still, he knows which way his bread is buttered: the graffiti also adorns a couple of canvases, placed there before the spraying started.

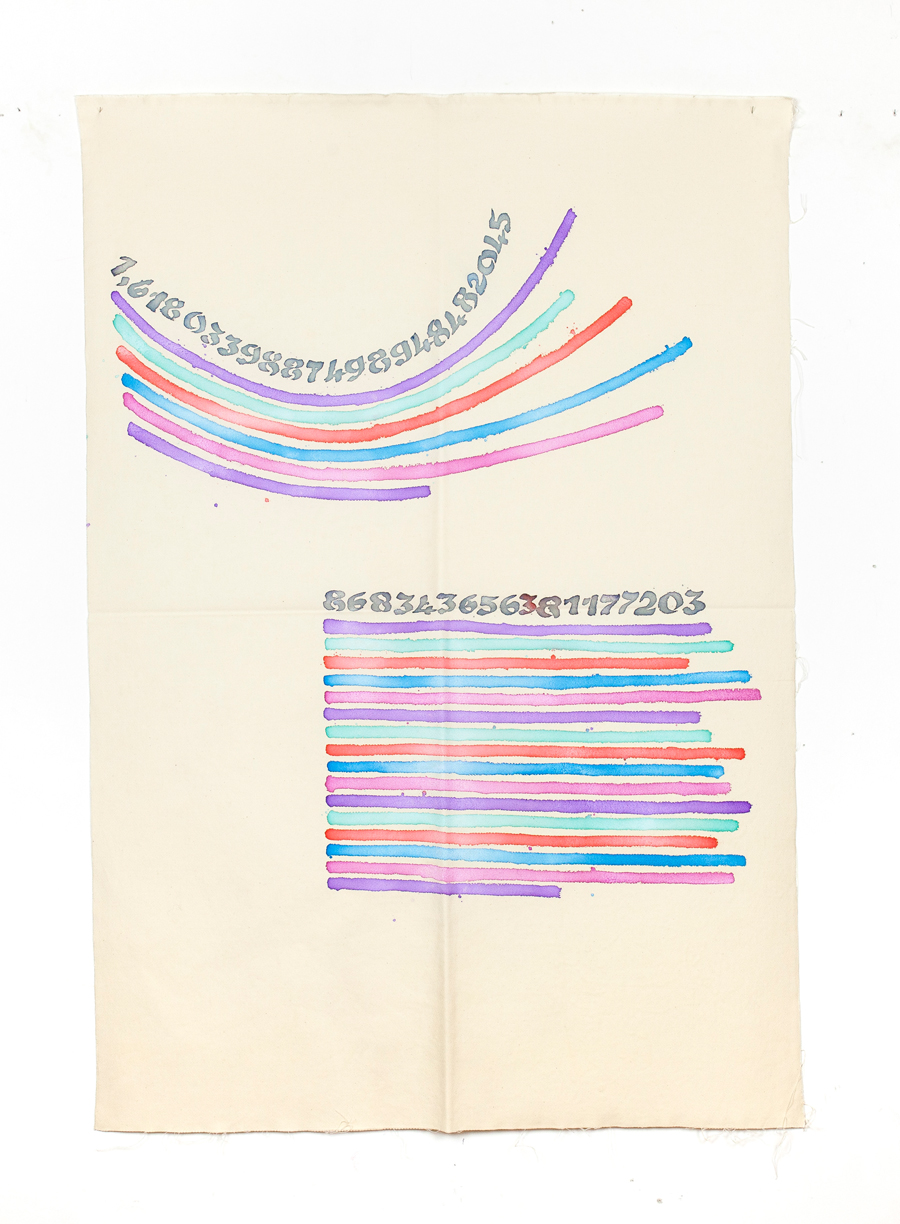

Lightness isn’t a problem for Giorgio Griffa, as Lorcan O’Neill’s refulgent, half-century-spanning ‘brief retrospective’ of 14 paintings by the 80-year-old Turinese master demonstrates. Griffa’s art, with its warm tiers of pastel stripes and code-like arrangements of numbers singing on unstretched brown or cream canvas, operates according to a kind of calculus, half-mystical, half-materialist: how attenuated can a painter’s language be and still be momentous, intricate, gripping? For a style linked to arte povera, his is paradoxically rich – it feels to contain within it the costless luxury of sunlight. And lightness, you recognize while navigating this show’s juxtaposition of old works and new ones reacting to them, has allowed Griffa to continue painting with a time-defeating vivacity; I couldn’t always guess what was recent here, though a new one was definitely among the best. In Canone Aureo 075 (2016), marching diagonals of ultramarine, aquamarine and various pinks and purples, interspersed with streaming lines of digits, slide into or out of the frame, as if the painter has just half-caught this graphic-numeric event going by and is sharing it with us. The effect is that of Griffa’s peculiar specialty: buoyancy with weight.