A Room of Once Owned: How Arts’ Collection Has Informed Its Curation

In ‘Décor’ at MOCA's Pacific Design Center, Barbara Bloom, Andrea Fraser and Louise Lawler unpick the etiquettes of the gallery space

In ‘Décor’ at MOCA's Pacific Design Center, Barbara Bloom, Andrea Fraser and Louise Lawler unpick the etiquettes of the gallery space

In her 1929 short story, ‘Lady in the Looking Glass’, Virginia Woolf issues a warning: ‘People should not leave looking glasses in their rooms.’ She writes that mirrors are intractable, hostile devices that can only mis-reflect their surroundings and threaten ‘the whole of that extremely complex form of femininity’ made possible within a room of one’s own. In Woolf’s story, the bedroom is a site of analysis for her narrator, who looks in the mirror hanging on the wall with hopes of finding out who the room’s owner is. Instead, she discovers ‘Ms. Isabella Tyson’ in discovering not only what she is not (marble countertops and other objects of ‘good taste’), but what she has not done: a heap of unpayable bills. Who, then, is she?

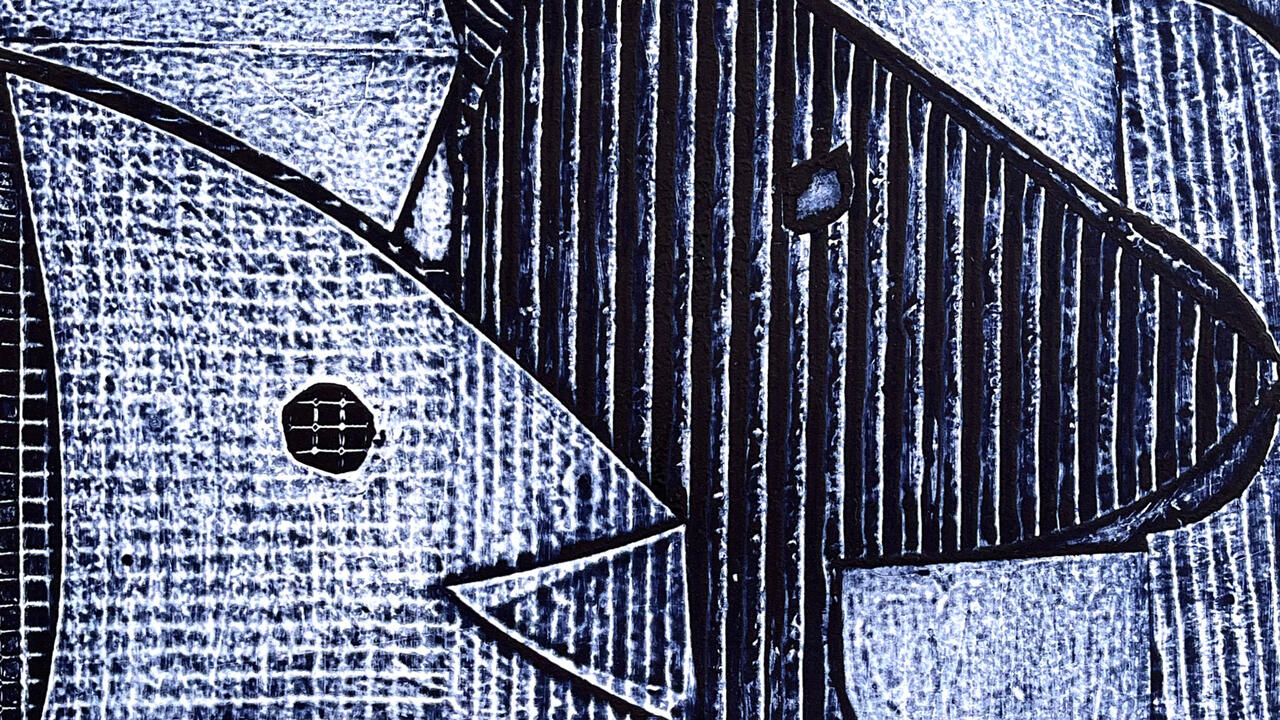

For ‘Décor: Barbara Bloom, Andrea Fraser, Louise Lawler’, now on view at MOCA’s Pacific Design Center, curator Rebecca Matalon repeats Woolf’s conceit so as to reframe what ‘one’s own room’ might signify. Rather than reflecting back their ‘owners’ faithfully, the rooms in the exhibition – centred around Bloom’s haunting installation, The Reign of Narcissism (1988–89) – draw attention to their extremely composed ‘arrangement’ (in Lawler’s term) within a museum context. ‘Décor’ brings together the work of three artists who, beginning in the early ’80s, used photography, video and installation to thwart the proprieties of art presentation and art collecting that have structured meaning within institutional and domestic spaces.

On the first floor, Lawler’s photographs depict museum minutiae and their surroundings. With nearly all hung at eye-level, the photographs emphasize Lawler’s interest in the slim margins and forgotten corners of gallery spaces, in scalar manipulation, and in the critical reformatting of art and aesthetic signs – specifically the tension between antiquity and 20th century art. Jade (Mint) (1994) zooms in on a delicate praying mantis, which the artist presumably found in a collection of ancient Chinese art. The jade mantis lifts its delicate tendril up in the foreground, behind which looms a towering vase of the same material. The mantis became a central iconographic preoccupation for the Surrealists (primarily for its cannibalistic act of coitus) and is, for Lawler, an exalted figurine of a different kind: a remnant of Eastern antiquity re-minted as ornament.

On an adjacent wall hangs Them (1986), a photograph of a green-tinged Roman bust – a forlorn looking man, sliced in half – rests against an unrelated, fragmented Roman frieze. The sculptures in this photograph are displaced objects, outside of the collection’s immediate context, and are photographed against a solid blue background. The ground on which the sculptures sit is also marble, distorting your perception of the statues’ size. This is only emphasized by Lawler’s placement of this print within a blue box-frame, which shrinks the towering torso within it. Above these, and near the top of the stairs of the first-floor gallery, hangs Lawler’s Pleasure More (1998–99), a photograph of Warhol’s ‘Silver Clouds’ sculpture. Pleasure More acts as the spatial hinge of the show, the image of weightless, floating silver balloons reading like material inversions of the solid figures Lawler photographs in Jade and Them. Within the photo, two balloons in the foreground blur as they glide into one another, as if signalling the quiet transit space these objects – the pictures and their frames – will traverse as they are moved between galleries and museums, from collection to collection.

Fraser’s videos capture how docents and patrons administer assignations of taste and value onto these objects and spaces alike. In her seminal Museum Highlights (1989), the artist plays the role of ‘Jane Castleon’, a fictional docent of the Philadelphia Museum of Art who, speaking into the camera, performs a walkthrough of the space (‘now we are in the bathroom,’ Jane instructs, ‘now we are in the gallery’) without providing any descriptive or historical context about the works surveyed. Like Lawler, Fraser here focuses on the space between a museum’s objects, rather than the objects themselves. But her videos focus more on the fiscal channels the works have travelled and the means by which works store value rather than on the calm of empty space. Unlike the other two videos included within the show, Museum Highlights plays from a loudspeaker, and Fraser’s monologue – flattening and genericizing the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s collection, pointing to the chairs and the tables rather than the works of art – speaks easily to the institutional setting of MOCA’s Pacific Design Center, where conceptual renderings of chairs and tables are typically displayed.

Upstairs, Bloom’s hexagonal installation, The Reign of Narcissism, with its pistachio walls – a pigment that reads a bit like bile, or, as an abject saturation of Lawler’s jade – takes us directly into the private museum collection. This eerie, rarely shown full-scale, faux-Victorian parlour is broken into disparate fragments, each of which refer to a fictional set of Barbara Blooms: bas-reliefs depict ‘Bloom’ among hovering cherubs; two Greek-style busts of ‘Bloom’s’ head sit on demi-columns; in the centre of the room, white silken flowers are literally mid-bloom in an opaque white vase. In one vitrine, 30 leather-bound volumes entitled The Complete Works of Barbara Bloom (1989); on the facing wall, three tombstones with vaguely artsy epitaphs – ‘She traveled the world to seek beauty’ – memorialize ‘Bloom’, proliferating the artist’s presence in her after-life. Looking around the room more closely, one notices that the walls of the installation itself have ‘Bloom’s’ name, etched into them, near the base of the entrance into the space. Bloom doubles down on the extant strategies of conceptual installation and their contextual ironies, blurring the lines between ‘herself’ and the context of collecting.

Standing within Bloom’s installation for a few minutes, Woolf’s double warning echoes: in this room, as in Lawler’s and Fraser’s, it becomes clear that you’re not standing in a room of one’s own; instead, the room itself has taken over, its artist becoming the very ornaments that comprises it. Like Woolf, who, here, and elsewhere catalogues the ‘perfectly empty’ mirrors and ‘odd and angular’ material possessions that adorn, and radically alter the lives and the work of women, the works exhibited in ‘Décor’ act as crucial reminder of the lavish manias that accompany the culture of collecting, and the highly controlled arrangements that structure our interaction with art and its many spaces.

Main image: ‘Décor: Barbara Bloom, Andrea Fraser, Louise Lawler’, 2018, installation view, MOCA Pacific Design Center, Los Angeles. Courtesy: The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; photograph: Zak Kelley