The Same Hand Paints It All

Malcolm Morley on soldiers, style and painting Jasper Johns

Malcolm Morley on soldiers, style and painting Jasper Johns

Born in London in 1931, Malcolm Morley studied at the Camberwell College of Arts and later at the Royal College of Art. Moving to New York in 1958, he embraced the heroism of the post-war American school, befriending the likes of Jasper Johns - whom he has described as one of his “alter egos” - and has remained in the area ever since.

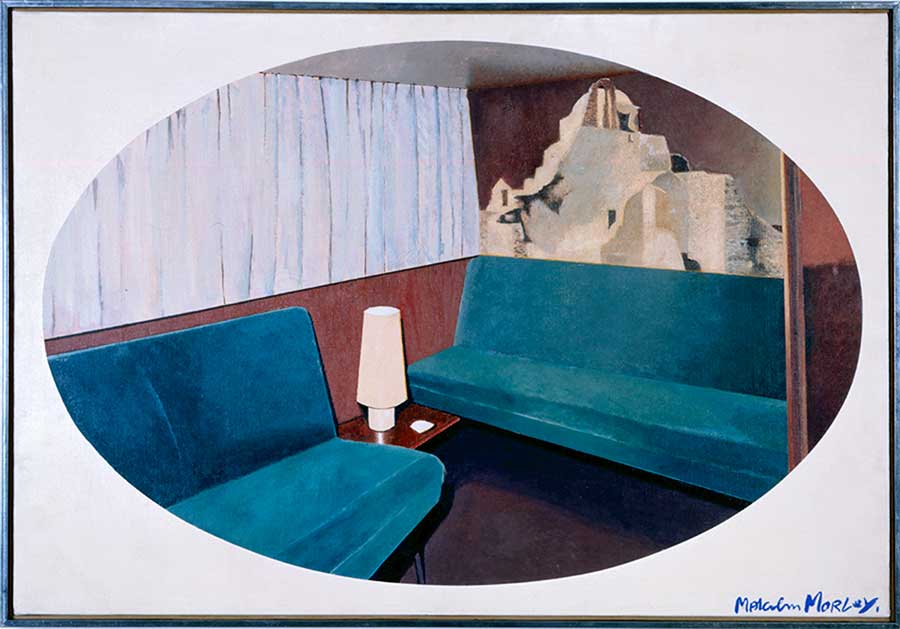

Morley received the first ever Turner Prize in 1984 for his first retrospective at the Whitechapel the preceding year. Sperone Westwater’s solo presentation at Frieze Masters 2017 spans works from the early 1960s to the current, including sculpture alongside the painting for which he is widely acclaimed. Sometimes hyperrealist, sometimes fluidly disembodied, and drawing on found imagery and 3-d forms, Morley’s painting displays an intense, ambivalent engagement with abstraction and figuration, representation and the imaginative re-creation of the world. Sir Norman Rosenthal has stated that Morley “wants to have his cake and eat it too [...] and he does.” The presentation at Frieze Masters constitutes the first survey of the artist’s work in his home city since 2001.

Frieze.com: The most recent painting in the survey at Frieze Masters is of soldiers in the Trojan War, and some of your most recent paintings, in a similar vein to Mortal Knight (1997), depict toy medieval knights. What appeals to you about these toy-like figures?

Malcolm Morley: The knight paintings are based on paper models, which were carefully built in my studio, then posed and painted. The models are historically correct, i.e. each figure represents an actual knight who fought in the Battle of Agincourt. In general I refer to the objects I paint as models. Toys are to be played with whereas models are to be looked at. What appeals from a painterly perspective are the patterns making up the object, the sense of Cubism in the shape of the armoor. They are very modern looking.

Frieze.com: Is there a continuity between these complex battle scenes and the violent action of earlier works such as Theory of Catastrophe (2004), or do they belong to different periods, with shifting concerns?

MM: I have no shifting concerns, only what is going to be the next painting in terms of my temperament at that time. The continuity is that the same hand paints it all.

Frieze.com: There’s a big retrospective of your peer Jasper Johns on view in parallel to Frieze Masters at London’s Royal Academy. How have your careers intertwined?

MM: When I first came to the United States in 1958, Jasper Johns was showing his ‘Target’ paintings. They hit an optical nerve in me I did not know I had.

In the early 1970s we all lived on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. At that time I approached Jasper with an idea, which would entail his going to a street portrait artist in Greenwich Village. He would pose for a portrait, and then I would make a painting from the portrait. The Village portrait artist made Jasper look like a 1930s crooner in pastel, but Jasper was very good-natured about it. Unfortunately all was lost when a fire destroyed the contents of my studio.

On another visit to his downtown studio in a former bank building at 223 East Houston Street, Jasper was working on his Map (1967–71), based on Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion Airocean World, which he was painting in wax encaustic. I was familiar with the medium, but his use of it was a revelation. The combination of the body of the encaustic against the body of another colour was so meaty, and the final polishing lent a hallucinatory and brilliant effect. Since then I have often used the medium in my three-dimensional pieces, such as Flight of Icarus (1993) and Trafalgar Cannon (2013).

Main image: Malcolm Morley. Photograph: Jason Schmidt. Courtesy: the artist and Sperone Westwater, New York