Sarah Sze’s Experiments of Collective Timekeeping

On the occasion of her show at the Guggenheim Museum, the artist discusses how shifts in scale and juxtaposition reflect an experience of time

On the occasion of her show at the Guggenheim Museum, the artist discusses how shifts in scale and juxtaposition reflect an experience of time

This article appears in the columns section of frieze 235, based on the theme 'Time Warp'

Erika Balsom In the press release for ‘Timelapse’, your upcoming exhibition at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, you are quoted as saying that the show is ‘an experiment in collective timekeeping’. Museums have always been timekeepers of a sort, but it strikes me that you are proposing something different and perhaps even opposed to the museum’s traditional relation to temporality. These days, while it may seem like we each inhabit our own time, it can also feel, more than ever before, like we are all subject to the same, singular time of networked communications – which is perhaps not a time at all, but a succession of disconnected presents. What is your interest in this idea of shared time?

Sarah Sze I’m thinking more in terms of a succession of disconnected presents, but I believe that there is a greater longing for arenas that are live, that create shared moments of serendipity.

Museums and artworks involve a specific kind of embodiment, but the digital realm carries its own forms of embodiment, too. People often create a false dichotomy in their minds between the online world, which they perceive as non-physical, and ‘real life’, which they deem physical. But the digital is also physical: it’s light and pixels; it’s a screen; it’s tactile and sensory. I like to question what each medium does well. For me, the digital has an incredible power to communicate longing. You always want more. This is something that the structure of the internet has capitalized on.

EB You mention the experience of the screen as something physical. You’re primarily known as a sculptor, but I have the sense that video is becoming an increasingly important part of your practice.

SS That’s the specific focus of the Guggenheim show. I have always been interested in teetering between something digital and something analogue, between an image and an object. Since the 1990s, that conversation has exploded in my life and in the world. The show parallels this: it traces that explosion in my work. There are two older pieces in the exhibition. One is called Media Lab [1998], which I made for Manifesta 2 in Luxembourg. It has videos projected amongst objects and was probably the first video I ever showed. The idea of flipping between the three-dimensional and the digital was something I was really interested in. The second one, the show’s other bookending piece, is Timekeeper [2016].

The filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein’s theory from ‘A Dialectic Approach to Film Form’ [1929] of how meaning is derived from the juxtaposition of two shots is an idea that is threaded through the way I use each medium in the show. Even my paintings are collages; they splice together digital printing, silk screen, acrylic, oil paint and objects. You’re piecing together the image. The medium of collage is so relevant right now to digital image-makers: it’s all about the collecting and collaging of images. We piece together a film in our lives, every day, with the disjointed images that come at us. In one day, we edit together images from entirely different sources: high, low, distorted by others and then distorted in our own hands. It happens so quickly, and without any certainty about authorship or authenticity. The idea of scrolling is very interesting to me as a form of editing that we do in real time, with a random group of images, most of them unchosen.

EB This discussion of the productive tension of juxtaposition makes me think of how your work is often associated with the re-use of mass-produced objects, but also tends to include natural materials, like stones and plants.

SS I had a friend, a figurative painter, who came to a show of mine. He said: ‘I love what you’re doing, because no one’s doing landscape anymore.’ This was in response to a show of my sculpture, and it was such a great entry into that work. I’ve always thought that I’m doing landscape, but not the depiction of landscape. The work imitates the behaviour of landscape, whether it’s entropy, growth or reproduction. I think the behaviour of landscape has always structurally been a subject of the work – an abstract subject, but a subject nonetheless. The work itself is, in some ways, a landscape in which unexpected moments of discovery happen. In my practice, elements of the natural world are juxtaposed all the time with things that are made by humans or that are mass-produced. The idea of having them right up against each other and seeing where you fall in between is important.

During that process, two things tend to happen: we verbally name the things we can see and we make an inventory of them. This is how we’re trained to re-establish our sense of location. When you take an object out of its context, it loses its meaning and becomes only a list of materials. It’s like looking at a sculpture by Eva Hesse and saying: ‘It’s three gallons of latex, three strings’ and so on, when the whole point is that these materials have been transformed by both their treatment and their location. Or, it’s like taking an Emily Dickinson poem and putting the words in listed categories – verb, adjective, noun – and then saying: ‘Isn’t this interesting?’ It’s not. People have a desire to dissect the work and take back control over the objects by turning them into words that can be understood.

EB It sounds like this tendency is a symptom of an anxiety that your work inspires concerning the life of objects and the relations you create between them.

SS That anxiety always comes back to death, right? The idea of the work is to create a situation in which you feel that you’re in the midst of a precarious experience. It prompts you to question where the work started, how it started and how it’s going to end. You recognize that you’re in this very pointed moment, in an arc that will end. For me, that’s where the anxiety is always located. Maybe it’s instinctual to try to re-establish a sense of security around that.

EB Speaking of precariousness, I wanted to ask you about scale. You’ve evoked the tradition of landscape, which suggests a sort of immensity, and you often work on a large scale. For many artists, scale and monumentality are more or less synonymous. Your installations, by contrast, disentangle the two. There’s a feeling of precariousness – a fragility or delicacy – which maybe also connects to this anxiety we have been discussing.

SS For me, scale is about undermining monumentality all the time. I try to create shifts of scale that move quickly between a sense of something very fragile, something in flux, to the feeling that a much larger perspective is in play. In the Guggenheim, I have installed a work in the rotunda, but it’s not a colossal piece. It’s a single string that hangs from the top level all the way down to the ‘pool’ six floors below, just tickling the surface. A lot of people overlook the fact that Frank Lloyd Wright made this amazing architectural decision to put a pool under a vast skylight in the Guggenheim! Entering the building is like walking into a space with a framed sky and a fountain at the bottom. To bring nature into the museum in that way is fascinating. I wanted to point to that almost literally, to make it the centre of the show. I’ve installed a single string – moving, because it’s being blown by an off-the-shelf fan – that extends all the way to the top of the building. You don’t realize it at first but, when you get to the top, it connects down into another pool of water. Then, when you return downstairs, you understand that the partner pendulum is moving at the same time up at the top, even though you can’t see it anymore. You imagine that connection, but you never get to see both up close. That, to me, is something you might remember and that, in ten years’ time, will make you say: ‘That happened in the Guggenheim.’ It doesn’t have to be big. It doesn’t have to be loud. It’s the measuring of scale not in centimetres or metres, but through impact on someone’s experience over time.

‘Sarah Sze: Timelapse’ is on view at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, USA, until 10 September 2023

This article appeared in frieze issue 235 with the headline ‘Shared Serendipity’

Read more thematic columns here

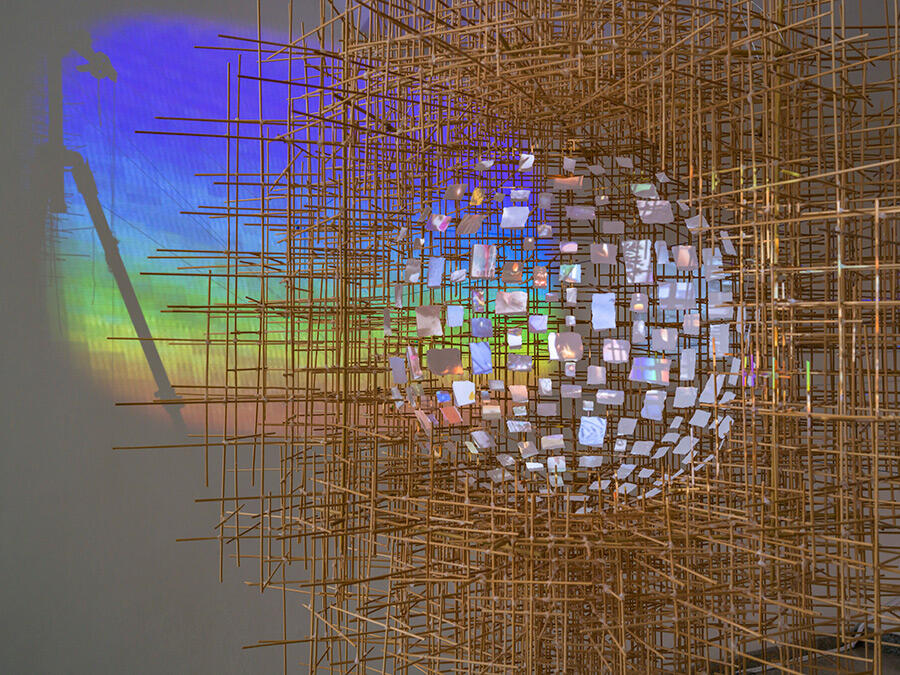

Main Image: Sarah Sze, Diver, 2016, installation view. Courtesy: © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York; photograph: David Heald