Saying No to Don DeLillo

The author’s latest novel, ‘The Silence’, is full of questions with obvious answers

The author’s latest novel, ‘The Silence’, is full of questions with obvious answers

Don DeLillo’s 18th and latest novel, The Silence, is brimming with rhetorical questions, most of which can be answered with a simple no. ‘Is this the casual embrace that marks the fall of world civilization?’ No. ‘Is Europe one impossible crowd?’ No. (It’s several.) ‘Isn’t it strange that certain individuals have seemed to accept the shutdown, the burnout?’ ‘Do a select number of people have a form of phone implanted in their bodies?’ No, no. ‘Am I being a little too self-important?’ A question perhaps better left unanswered.

The Silence is the kind of book that wears its flaws so proudly they start to seem like virtues. It’s occasionally easy to laugh at, but it has a knack for turning your laughter against you, leaving you weary and defeated and maybe a little awestruck. Sure, it doesn’t always make sense, but does anything right now? (No, again.) The novel has a lot in common with the hushed, intangible disaster at its centre: on 6 February 2022, during Superbowl LVI (Seahawks vs. Titans), the power abruptly shuts off in Manhattan – and possibly everywhere else on earth. Shepherding us through the blackout are five main characters: a jet-setting couple, Jim and Tessa, and a ménage à trois consisting of Diane, her ex-student Martin and her husband Max, who takes talking to the television to chilling extremes.

Rumours that this is the first Covid-19 novel have been greatly exaggerated: though our subject is a global catastrophe, clues as to its causes are limited to a couple of terse, lacunar passages. The novel’s epigraph is the old Albert Einstein chestnut – ‘I do not know with what weapons World War III will be fought, but World War IV will be fought with sticks and stones’ – and DeLillo takes the point as literally as possible. If this is indeed the start of World War III, nobody seems to know whether nukes, EMPs, Anthrax spores or cyberattacks are to blame. Denied certainty, the characters drift together and apart on an idle breeze of plot.

Since Underworld (1997), DeLillo has scrapped more and more of what his readers once recognized as DeLilloesque: the humour, the jittery plots, the fearless sci-fi inventions, the cascading sentences punctuated by tart aphorisms. As a stylist, he can still hit it out of the park: in the first few pages alone, he gives us ‘a brief stab of laughter’, ‘the nudge of dumb indulgence’, and ‘Kripps was a tall man’s name.’ The third phrase is perhaps the most characteristic; James Wood was spot-on when he described DeLillo’s classic style, in a 2007 review in The New Republic, as ‘somehow exact and mysterious, in the right proportions’. With the new millennium, however, mystery has eaten away at exactitude, and the prose has suffered.

In much of his late work, DeLillo flirts with self-parody; in The Silence, he practically gets down on one knee and asks for its hand. Of Max’s involuntary muttering, he has this to say: ‘Half sentences, bare words, repetitions. Diane wanted to think of it as a kind of plainsong, monophonic, ritualistic, but then told herself that this is pretentious nonsense.’ That neatly sums up the experience of reading this novel – at many points, I was tempted to surrender to its compressed, unadorned phrases, only to recoil in disgust. Of Martin, DeLillo writes: ‘It was the name that gripped him. The beauty of the name. The name and place.’ The name is ‘Jesus of Nazareth’; no further explanation is offered. DeLillo is a master of the weird, just-plausible non-sequitur: nobody who has read White Noise (1985) could forget that its protagonist, Jack Gladney, is a professor of Hitler Studies. Yet, here, the characterization isn’t close enough to the character to be funny or surreal: it’s DeLillo, not Martin, who is ‘gripped’ by the name, DeLillo who tosses this quirk at Martin, when he could have tossed it at Jim or Tessa just as easily.

Mystery trumps exactitude at the narrative level, too: we’re denied the comforts of exposition and coherence; even the Einstein quote, much fretted over by Martin and Diane, turns out to be something of a dead-end. I imagine this is the point but, if so, I don’t see what the novel tells us that the last four years’ worth of news hasn’t told us many times over: the haute bourgeoisie are a bunch of frauds; civilization is a mile wide but an inch deep; and, at a global level, malice is indistinguishable from incompetence. It’s fitting, then, that The Silence’s typical form is the thumping rhetorical question; the more you think about it, the less you get.

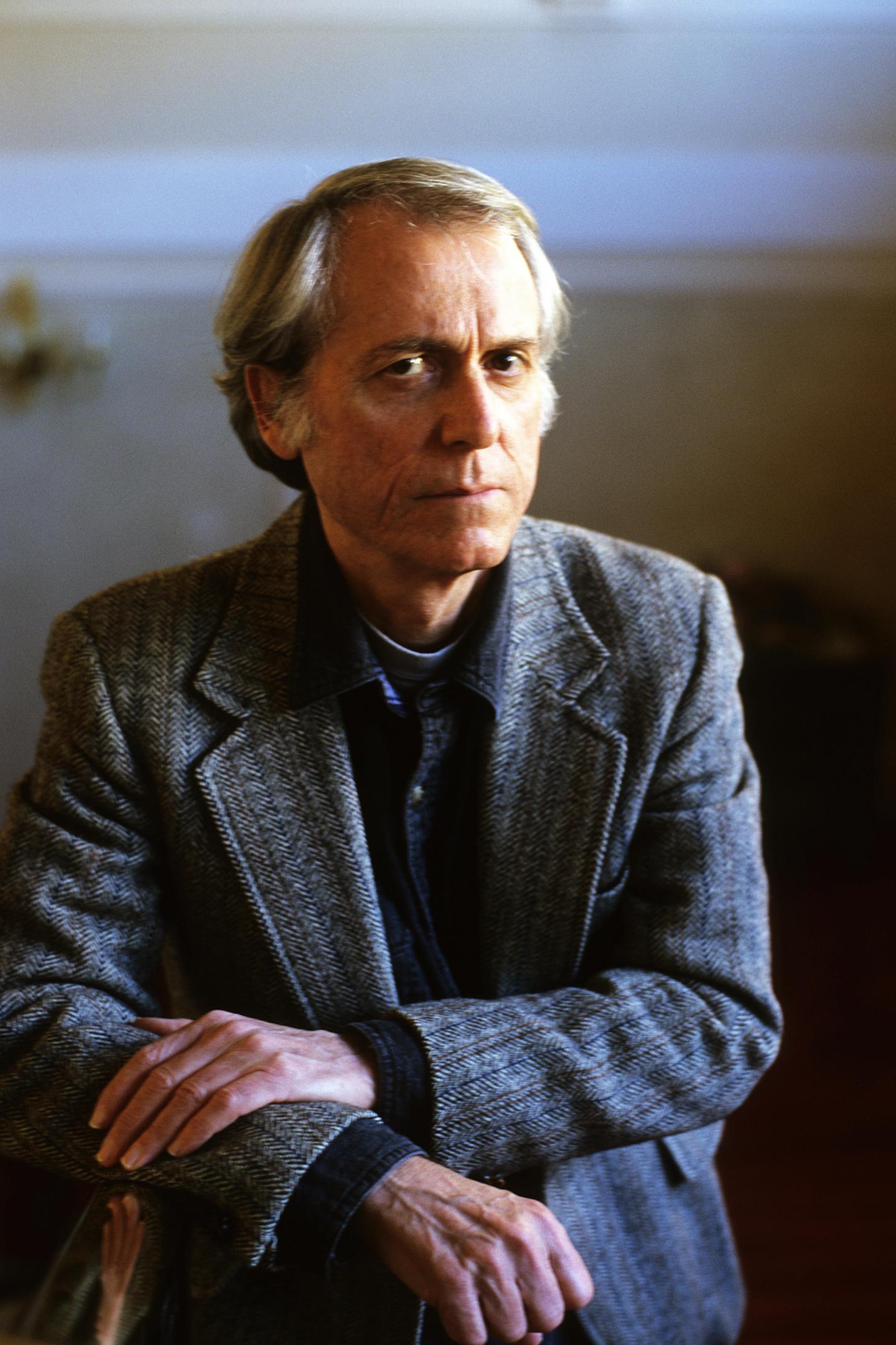

Main image: Don DeLillo, 2000. Photograph: Leonardo Cendamo/Getty Images