Seeing Red

Two films examining German terrorism

Two films examining German terrorism

Volker Schlöndorff's film Die Stille nach dem Schuß (The Legend of Rita, 1999) premiered at the Berlin Film Festival in February 2000. Towards the end of the same year a photograph appeared in the German press showing Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer involved in an attack on a policeman during a 1974 demonstration. Fischer was consequently criticized for his radical left-wing past, which in turn led the German public to reassess the ideologies of the 1968 generation.

To a certain degree, Schlöndorff's film (about a terrorist hiding-out in the GDR) anticipated this controversy. After years of neglect, it undertook the obviously loaded task of exploring the history of left-wing terrorism in Germany. Die Stille nach dem Schuß is based on the autobiography of former Red Army Faction terrorist Inge Viett, who, after initially co-operating with the filmmaker, went on the offensive in public to complain bitterly about the 'cinematic distortion' of her life. Thus the film marked out the problematic intersection of subjective perception and media processing, of personalization and myth-making - the crossroads at which current debates about 1968 generally find themselves.

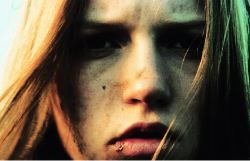

Schlöndorff's attitude to his subject is midway between a defence and a hagiography. Within a rather naive portrayal of left-wing terrorism, which concentrates on the emotional problems of living underground, he attempts to portray the terrorist as a complex character with whom we can identify. Whether depicting her at a barbecue with a friendly Stasi officer, working at a textile factory or undergoing relationship problems, Schlöndorff pursues every detail in an attempt to provide the most authentic portrait possible of his underground heroine's daily life in the GDR. Paradoxically, however, it is precisely this process of reconstruction that causes the political dimensions of his theme to narrow. By sticking to the 'facts', the film touches upon topics such as whether or not you should fall in love while in hiding, or what to do if your cover is blown. But the obvious question that suggests itself - what happens to anti-capitalist Red Army Faction ideology in the reality of the anti-capitalist GDR? - is not raised. Schlöndorff's heroine, head held high, strides through the system with imperturbable integrity, a timeless icon of resistance movements everywhere.

Whereas Schlöndorff moves from personalizing to mythologizing, Christian Petzold's film about the Red Army Faction goes in the opposite direction. Die innere Sicherheit (The State I'm In, 2000) opened in German cinemas almost a year after Die Stille nach dem Schuß - at a time when the debate about the generation of 1968 was focused on the trial of Hans-Joachim Klein, accused of participating in the Vienna OPEC attack of 1975. The major difficulty at the trial was to reconstruct events from anecdotes about communal life, faded memories and hazy recollections of conspiratorial meetings. Joschka Fischer was called as a witness, whereupon the public vehemently debated whether he was really able to recall, more than 20 years on, if he had once had breakfast with Red Army Faction member Margit Schiller, then a guest in a neighbouring communal flat. The seeming clarity of 1960s and '70s ideology and utopian visions contrasted starkly with the remoteness of the concrete historical events under discussion. In his written adjudication the presiding judge admitted being hopelessly stymied by 'a quarter of a century of time gone by'.

Die innere Sicherheit is a film that takes up temporal distance and the blurring of facts as a challenge. Its young director has created an abstract portrait of a generation, an almost shadowy sketch of a left that has retreated into itself and is no longer capable of connecting with the outside world. In the film the Red Army Faction, post-1968 utopian dreams, the 'German Autumn' of 1977 and world revolution, are embodied in a nuclear family unit of a terrorist couple and their daughter. The triangle of mother, father and child becomes a metaphor for the residue of those heady days of dreams and struggle.

The family in Die innere Sicherheit appears as a fortress in which irreconcilable revolutionary and bourgeois longings co-exist. Although they have lived underground for years, the couple's daughter, now an adolescent, begins to demand the right to live the life of an ordinary teenager. Owing to its emphasis on psychological interplay, the film describes the tension between maintaining left-wing resistance and becoming bourgeois (between marginalization and integration) while sustaining a degree of abstraction that leaves the terrorists at an uncertain distance. Again and again one sees the family in a car, in a telephone box, in a snack bar, or completely exhausted at one of the many apartments and hotels that serve as intermediate stopovers. 'Why did you have me?' asks the daughter from the back seat of the car, which has become a kind of substitute for her teenage bedroom.

With this rootless trio constantly on the run Petzold has captured the status quo of a generation that has drifted into privacy (and in some cases paranoia) while still being stylized and mythologized - not least by its ideological opponents. Schlöndorff claims to show us how German terrorism really was; Petzold proves himself more sensible by showing us how it might have been.