Carrie Mae Weems Reclaims Black Female Subjectivity

The poet and critic Simone White considers the artist’s formative work Mirror Mirror (1987–88)

The poet and critic Simone White considers the artist’s formative work Mirror Mirror (1987–88)

Carrie Mae Weems is the best-known photographer of black women in the world, now or ever. Mirror, Mirror (1987–88) is among the most famous pictures she has made. I’m obliquely asserting that black femininity is not contained within the black woman’s body; also, thoughts about her cannot be engulfed by visible representations of her body. Or, in this case, her face. I believe that I belong to a community of black women but/and knowing anything about being a black woman at this sad-ass moment in time means that I can only see my true (sexual) self in a hall of mirrors: that is, I am visible everywhere, no matter what optical distortions are imposed upon my form. I will not protest having been overtaken in the mirror by distortions, having been in shadow or eclipsed. If only mere invisibility and not total shattering – annihilation – were at stake when the mirror shouts at the black lady shyly seeking affirmation that she is, indeed, ‘fine’, ‘SNOW WHITE, YOU BLACK BITCH, AND DON’T YOU FORGET IT!!!’

Snow White! She is looking askance, aside, from the white-looking femme figure whose icy element is a star. She could not see her self in the mirror, but we might read the white occult response to ‘WHO’S THE FINEST?’ as ‘You is Snow White! [expressing surprise, resentment, confusion] + YOU [is a] black bitch and don’t you forget it, although the white occult feminine is what appears in this mirror as “your” image.’ Magic isn’t real, but light is, so isn’t the question: ‘Who is that (apparently) white apparition talking to?’ Is she talking to herself? And, if so, what kind of psychosis is this a picture of? Alternatively, what if this impossible refractivity reveals precisely the impossibility of the second person within this circuit of abuse?

Lorraine O’Grady’s seminal essay on the black female body in visual art, ‘Olympia’s Maid: Reclaiming Black Female Subjectivity’, was first delivered as a talk in 1992. The maid in question is, of course, the black person depicted in Édouard Manet’s painting Olympia (1863).

What I am proposing, is a reading of what I can – and can’t – see in Mirror, Mirror as a permanently inscribed performance of an unrecoverable bloc of sensations relating to the possibility of ‘reclaiming black female subjectivity’. The sense of O’Grady’s intended reclamation is unrecoverable insofar as such a possibility belongs to the historical belief that subjectivity could pertain to the Others of Western thought – blacks, women, queers; that we could be restored to subjectivity and included in the socio-political world as bearers of rights and human dignity. Hortense Spillers was in the process of crushing that belief with her bare hands in the late 1980s and early ’90s (that’s a flesh joke). Because of Spillers, I cannot use the word ‘subjectivity’ without hesitation so grave that it completely blocks language, stops me from going on.

Weems was of the devil’s party that made works that functioned, in O’Grady’s words, as ‘pressure points intense enough to lure aspects of the [black woman’s] image from the depths to the surface of the mirror [and] then synchronously, there must be a probe for pressure points […] These are places where, when enough stress is applied, the black female’s aspects can be reinserted into the social domain.’ Synchronously brings attention to the part of O’Grady’s essay that I find indispensable: her description of the space of art that belongs to the black woman’s difference. Her particularity, and perhaps relatedly a measure of her power, does not arise from her capacity to represent the existence of ‘obverse and reverse’ significations of racialized womanhood. What she does, if she is making serious contemporary art, is image (Denise Ferreira da Silva’s verb) the inadequacy and decline of discursive and image materials that are currently available to conceive of her conditions. The black woman artist is always joking; she is always feigning the adequacy of the language, the inadequacy even of signifying, to communicate the aspects of herself that will have autonomy in a social world but not today.

She is the chaos that must be excised, and it is her excision that stabilizes the West’s construct of the female body, for the ‘femininity’ of the white female body is ensured by assigning the not-white to a chaos safely removed from sight. Thus only the white body remains as the object of a voyeuristic, fetishizing male gaze. – Lorraine O’Grady

... you are breaking the code of the working class by aiming to be a big cheese. I always wanted a bite of that cheese … – Eileen Myles

This essay is inspired by (and steals its title from) Eileen Myles’s essay on Pope.L’s ‘A Negro Sleeps Beneath the Susquehanna’ (1998). Another model is Wayne Koestenbaum’s chapter on Maria Callas in The Queen’s Throat (1993). Both are exemplary forms of poetic reflection upon an artist’s body of work and of writing becoming a form and instance of difference; difference that is partly expressed as sexual difference, or sexuality. Writing as a performative art of gendered expression – being and being seen as one who desires and is desired – as thinking about how this being-one is projected upon a commune, which Koestenbaum reminds, may be wishful and hypothetical. Holding somewhere, combatively, at the edge of what I’m writing is the idea that acts of fucking cannot engulf all of desiring and sex – an idea that animates Koestenbaum’s book Andy Warhol (2001). Myles’s ‘What I Saw’ is dated 1999–2009, but I think of it as belonging to a turn in time where it was possible to definitively notice the end of identity politics that the other two essays I’m thinking about here are right in the middle of. Like I said, this writing, mine, is an admiring offshoot of a kind of writing Myles does as part of a practice of thinking about who gets to be an artist-intellectual and, having taken permission and opportunity to be that, what searching moves and poses are possible in an encounter with something you don’t know about and are trying to discover poetically. Their style is to work small and reveal almost everything about the systems and times within which the work is taking place. I think Myles’s casual, shocking intimacy – the methods of appearing in the processes of invitation, study, making, being qualified; not to mention their poignant and abundant gifts of understanding – interrupts, denies the supremacy of ratioed looking/describing.

‘Olympia’s Choice’ (1984) – T.J. Clark’s essay on Manet’s Olympia, which excavates contemporary salon reports – helps me to understand what I, as a latecomer to Mirror, Mirror, am brought by Weems to see. ‘What happened in 1865 can be briefly stated,’ Clark writes maddeningly and stupidly, omitting any mention of the US Civil War in a discussion of the world-scale re-organization of attitudes regarding sex and labour. But the petty scenes of critical misapprehension he records show critics responding with huffing good sense to Manet’s rendering/arrangement of white prostitute (dubbed ‘female gorilla’ by Amédée Cantaloube in Le Grand Journal, 1865), negress servant and black (pussy)cat as harbingers of a radically altered and threatening future. The painting implies and requires disfigurement, and demands of viewers some intuitive response to emergent changes in the orders of racial capitalism. ‘Chiffre en dehors des êtres sociaux,’ Clark keeps quoting one of the salon people unironically. He writes about the confusion of contemporary critics of the painting but really should be talking about hisself.

Pussy pussy pussy gorilla (huh???). It is simply impossible to separate these creatures from one another. The pussy is not double, it’s dizzyingly numerous and leaks the infected jizz of all its couplings everywhere. No one wanted to be alerted to what modernity had wrought in 1865, what killed Abraham Lincoln.

I follow a Nigerian-Irish guy on TikTok who sets up scenes of recognizable interpersonal, often erotic, conflict, usually as both persons, marking gender difference by wearing a worn-out pink housedress and satin bonnet on one of the duet screens and some regular man-clothes on the other.

Man: you like me? Now I have to ghost you and treat you with zero respect.

Woman: but I like you now, you’ve been trying to get my attention for months.

Man: shut up, you black mango!

A black mango is apparently a real thing, but the humour in the abusive epithet comes through categorical confusion of fruit, colour, racially ascribed idiocy, oppression and the mix of all the things that produce rage and disgust in the speaker as he attempts to love. We laugh not only because the comedian engages in ‘commemoration’ – to misuse bell hooks’s phrase – of black diasporic common senses of the absurdity of romantic norms and the make-do operations within them, but because s/he is, at the same time, ‘you black mango’ and the maker of the scene, holding the apparatus of mutual regard – the camera/mirror – in his hand, seeing the viewer seeing him taking a bite of that cheese.

SNOW WHITE YOU BLACK BITCH, AND DON’T YOU FORGET IT!!!

a) I am the finest bitch out here.

b) It is not even clear that the white occult is not also a black bitch in her church hat and all, so, see previous paragraphs.

c) The black woman knows better than to ask ‘the mirror’ anything.

‘Carrie Mae Weems: Reflections for Now’ is on view at Barbican Art Gallery, London, from 22 June until 3 September

This article first appeared in frieze issue 236 with the headline ‘What I Saw’

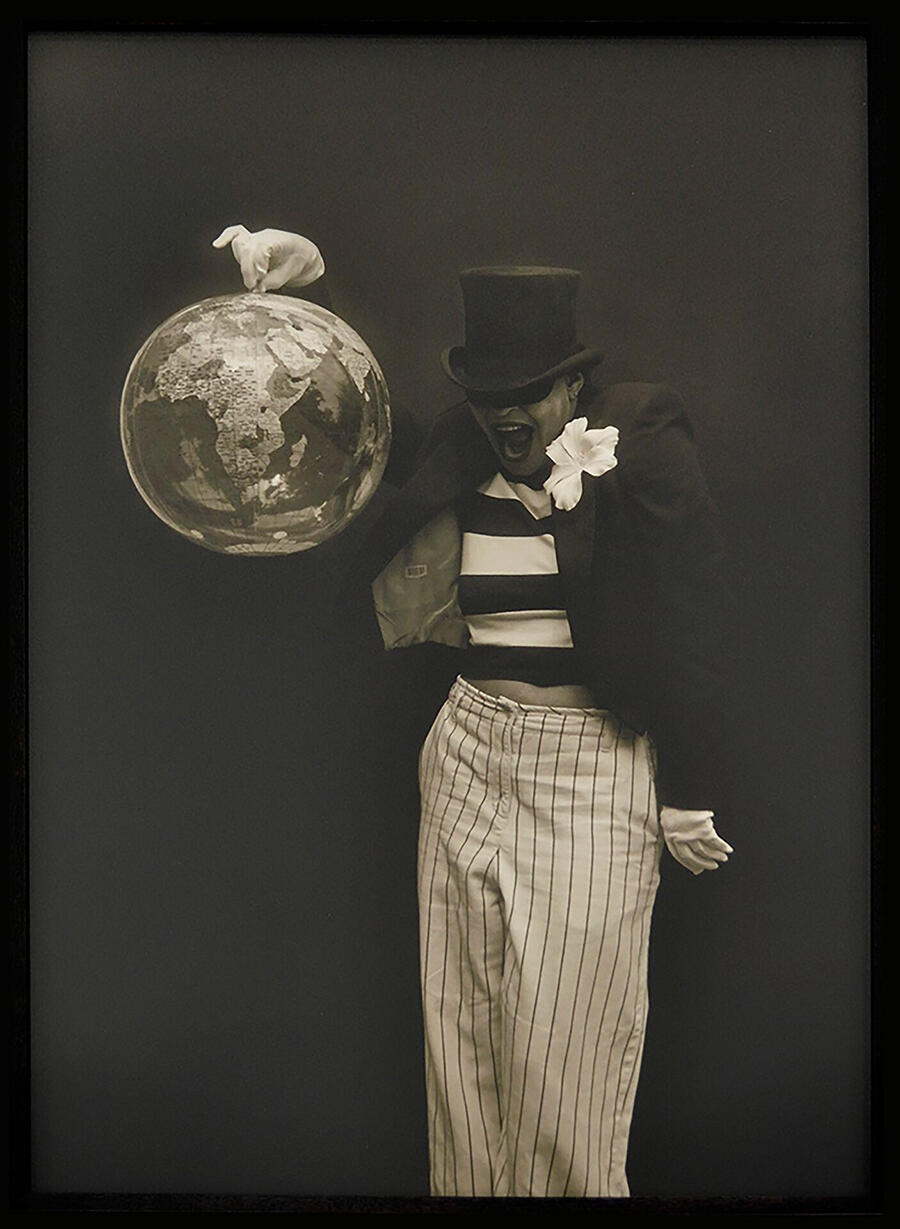

Main image: Carrie Mae Weems, The Joker, See Faust, 2004, archival pigment print. Courtesy: © Carrie Mae Weems, Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, Galerie Barbara Thumm, Berlin and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco