Site Lines

The removal of the Confederate monuments in Baltimore shows decisiveness after years of inaction – already they stand as sites of counter-memory

The removal of the Confederate monuments in Baltimore shows decisiveness after years of inaction – already they stand as sites of counter-memory

For the past five years, I have worked at the MICA, a progressive art and design college in central Baltimore, Maryland. Its buildings are set alongside a broad avenue that terminates near the former gates of Druid Hill Park, and the neighbourhood itself was constructed in the late 19th century from parcels of land drawn from larger estates. To my knowledge, no major battles of the civil war were fought here, and this, the Bolton Hill area was initially figured as a suburb at the northern city border. Nonetheless, it is dotted with sculptural forms. From the conventional man-on-a-plinth style, dedicated to a hero of the Mexican-American War, to the contemporary: playful, post-minimal forms appropriate to MICA’s longstanding engagement with abstraction.

Against this backdrop, it was easy to ignore the seemingly antiquated form of an angel cradling a man, holding a wreath aloft. Sentimental if vaguely martial, it faded into the backdrop on my morning walk to and from my office. Ensconced in trees it was vaguely reminiscent of the various monuments one might see walking along London’s Victoria Embankment. Of course, this statue, Confederate Soldiers and Sailors Monument (1903) is gone now, removed with three other pieces early in the morning hours of 16 August by the demand of the Baltimore City Council and on the instructions of its mayor, Catherine Pugh.

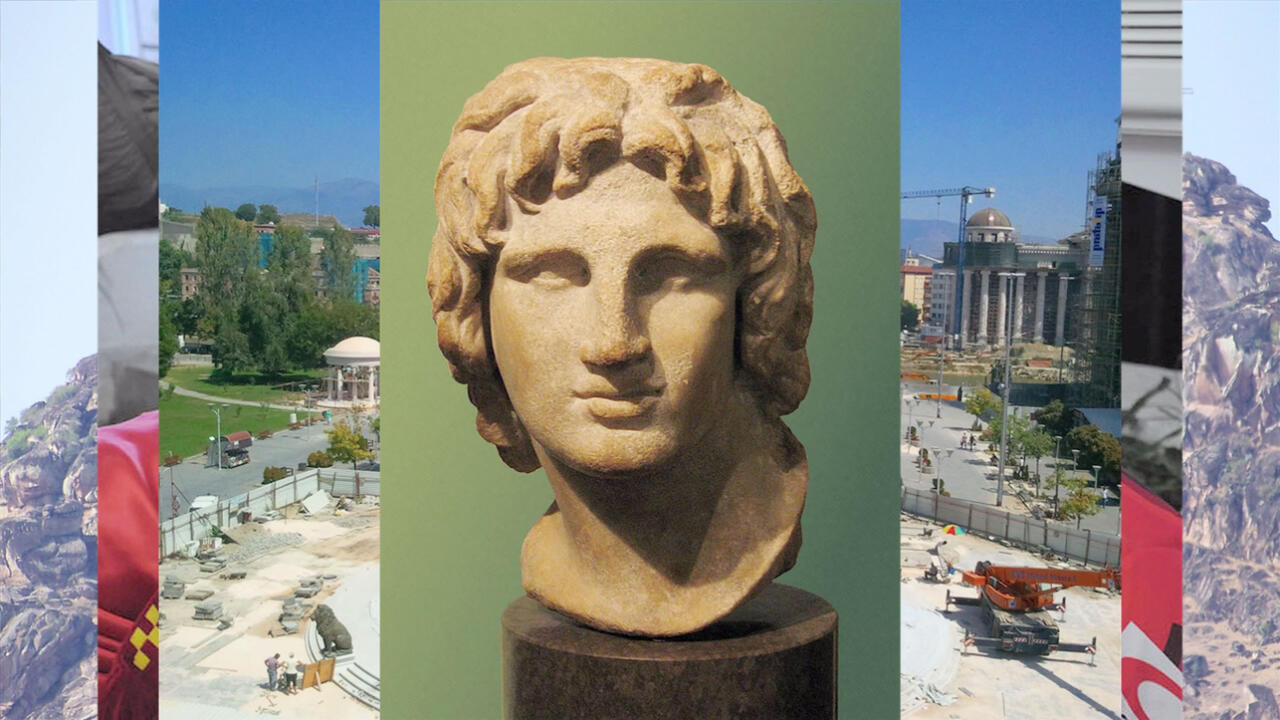

Debate has been steadily building around these Confederate monuments – those dedicated to the memory of the breakaway government that catalyzed the American Civil War in 1861 – during the past several years, but the pace this week was swift. For one, the soldier held by Winged Glory, while apparently discussed over the years, was seemingly not as overt a Confederate symbol as the statues of Generals – such as Stonewall Jackson – astride their horses, near Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, or lining the high street of the Virginia state capitol of Richmond. As I watched the Baltimore uprising unfold in this very neighbourhood two years ago, protestors alighted on local shops and rallied in the streets but unlike the student-led demonstrations that led to the removal of the Cecil Rhodes statue at the University of Cape Town in 2015, or the forcible toppling of the monument in Durham, North Carolina earlier this week, Baltimore’s Confederate monuments were bypassed, left to academic discussion: calls for the renaming of some public parks, the addition of nuanced placards, and the occasional defacement by paint.

It is telling, however, that the presence of the monument near MICA was, I think, easy to overlook. Its meaning so overt, sited like a thorn in a majority-black city, juxtaposed against a deep-blue populace and a socially-engaged, left-leaning community of young artists. When I moved to Maryland, I reconciled these contradictions to the state’s own ambivalent history – one founded on tobacco planting, but which apparently never reached the industrial-scale slavery of its neighbour Virginia before its delayed abolition in 1864. Maryland forms the southern frontier of the Mason-Dixon line, but counted itself among the Union states. Baltimore is the southern-most northern city, and the northern-most southern city. These are the liminal borderlands of a longstanding cleavage in the national imaginary.

In this light, it seemed possible to court a sort of denial, consigning the aging monuments in Baltimore to the fog of an antebellum past, to the deep relativism of a distinct historical moment, or to disavow that in a supposedly post-racial America such a commemoration could resonate beyond the innoculatory power of a cautionary tale. But many recognized the strange breaks in the arc of history that such monuments nonetheless initiated. Several years ago, my MICA colleagues Christine Manganaro and Nate Larson began a project during which they spent their free time seeking out such Confederate monuments, up and down the eastern seaboard.

Context is important here: Manganaro has noted that such monuments are largely the work of a kind of nostalgic fabulism – often erected on sites unconnected to the Civil War and well after the fact (the Winged Glory piece was made in multiple, apparently deployed elsewhere to commemorate fallen Union soldiers). According to her research, ‘the balance of monuments overstates Marylanders’ loyalties to the Confederacy and its military leaders. This imbalanced account also holds us back from fully reckoning with the legacy of white Marylanders who were anti-slavery and pro-Union, but remained committed to white supremacy.’ And, as many have noted this week, the commissioning of these monuments was undertaken over several decades, coinciding with turning points in the history of the American Civil Rights movement and the resurgence of reactionary violence by heritage groups or the earmarking of funds by local elites – idiosyncratic gestures that nonetheless crystalized a dangerous undercurrent.

In the wake of the bloodshed in Charlottesville – several hours to the south but seemingly worlds away – I watched my social media feed refresh with images: first of fresh salvos of graffiti and sloshes of crimson paint activating the statues anew, until suddenly the statues were gone. The Baltimore decision was powerful precisely because it finally cut through the ambivalences and ambiguities that have long justified the very presence of these monuments – no gradualism, no genuflecting to the pieties of ‘historical value’. Fittingly, I read about it in international headlines while visiting the ‘Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power’ show at Tate Modern, London, and it was clear that while statues have been coming down gradually throughout the United States, Baltimore added a galvanizing momentum to localist intervention in the face of federal inaction. There will be many more removals in the weeks and months ahead.

For now the plinths remain, and already they are becoming sites of counter-memory – of locals taking selfies with arms held high in a moment of quiet triumph, or the installation of alternate monuments, such as Pablo Machioli’s Madre Luz (2015), a massive papier-mâché form of a pregnant mother bearing a child and raised fist. Machioli has deployed it at the 1946 Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson monument before, only to have it removed. It appeared again this week, painted and repainted, toppled and righted again. Contrary to claims that the removal of the Baltimore Confederate monuments amounts to a quashing of ‘history’, these sites have been reactivated as a zone in which the past is re-animated and interpreted in real time, rather than calcified as monoliths of banal consent.

Main image: Detail of the Confederate Soldiers and Sailors Monument (1903) covered in red paint prior to its removal by the Baltimore City Council in the early hours of Wednesday morning 16 August, 2017. Photograph: © Nate Larson