SO – IL’s Architectural Commitments

Ahead of the opening of kurimanzutto New York this November, Adam Smith-Perez profiles the team behind the gallery’s new space, architectural studio SO – IL

Ahead of the opening of kurimanzutto New York this November, Adam Smith-Perez profiles the team behind the gallery’s new space, architectural studio SO – IL

As teenagers, the founders of New York architectural studio, SO – IL, Jing Liu and Florian Idenburg, reflected on the history of the built environment around them. When Idenburg was 16 years old, he wrote an essay about the ethical conflicts in the working life of his great uncle, iconic Dutch architect Hendrik Petrus Berlage – a man, Idenburg explained to me, who sympathized with socialism and visited Russia, but also built ‘massive hunting castles for industrialists’.

Liu was a boarding school student when she became sensitive to her material surroundings. Liu cites her hometown of Nanjing, a city of waterways in an agricultural region of China (and former capital city), as a major influence on her aesthetic framework. When she moved to Tokyo and then London for school, she remembers the respective energies of each cityscape, and how different they were from where she grew up. Liu recalls the beautiful old sections of Tokyo, but also the sprawling, dreary concrete outskirts constructed hastily after earthquakes and World War II. Liu remembers London’s stately and massive stone buildings, and the feeling that such imposing architecture ‘could also very much weigh you down’. ‘I’ve always liked the world building quality of literature and writing,’ she tells me. ‘And I became aware that the material life around you – the architectural and urban environment – have that same capacity to build a world where you become a subject, and a part of that world.’

In 2008, the year that Liu and Idenburg founded SO – IL (an acronym that stands for ‘Solid Objectives – Idenburg Liu’), architecture, like nearly every other professional sector, was devastated by the financial crisis. In their 2010 design for MoMA PS1’s Young Architect’s Programme, Pole Dance, Liu and Idenburg proposed a design-oriented corrective to the palpable pessimism of the time. The project was a mobile installation – the rationale being that in a recession there was little point designing a commercial or residential space. Based on only a single drawing and built in trial-and-error fashion on site, the installation was structurally unpredictable and collapsed several times before the opening date of the programme’s related exhibition. Playful by design, Pole Dance was driven by Liu and Idenburg’s conviction that a global economic crisis offered an opportunity to experiment with a new paradigm for urban architecture, one characterized by new technology, interactivity and the exploratory use of everyday materials. Pole Dance transformed PS1’s empty courtyard into an immersive, multi-sensory summer playground. ‘We designed the exhibition to look like a game, except there were no rules,’ is how Idenburg describes it.

The installation comprised a series of interconnected nets and poles, blow-up pools, sand pits and yoga balls. Museum-goers spontaneously started to organize the balls by colour – green, blue and orange ones peppered the space – and invented other do-it-yourself activities involving both the provided materials and the space itself. With the help of structural engineers and sound experts, SO – IL installed poles with accelerometers programmed inside of them, generating soundwaves when visitors shook them, controllable in volume and even visualizable through an iPhone app (both Liu and Idenburg were fascinated with emerging artificial intelligence technology). PS1’s Pole Dance certainly offered New Yorkers an idealism-driven outdoor party (SO – IL’s original proposal had promised it would be both ‘calming and carousing’) but it also marked the debut of the kind of community-oriented, interactivity-driven design that was to become the studio’s hallmark.

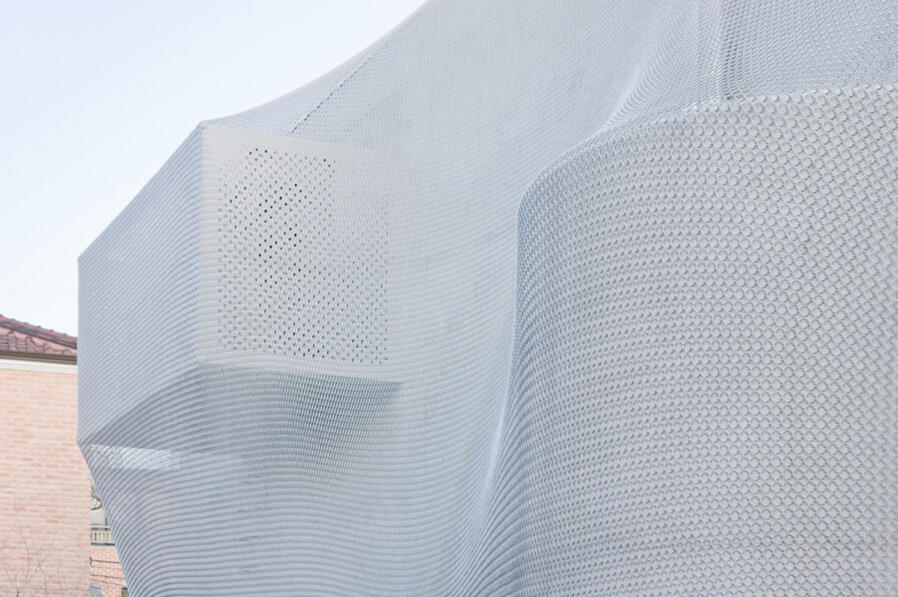

Around the time that Pole Dance was commissioned, so was a design for Kukje Gallery, which was located in one of oldest districts in Seoul. With this project SO – IL had to address the tension inherent in creating an art space that was not only a classic ‘white cube’ but also in some way true to the architectural history of the local district. They arrived at the site with a ‘big box foundation’ already built, and were tasked with integrating a very restrained structure into a neighbourhood full of hanok homes: delicate traditional masonry constructions with hand-built tile roofs. According to Liu, the studio decided to work with a similar ‘language of assembled materials’. After much consideration, a mesh was designed to cloak the entire gallery: 510,000 metal rings (enough to create a soft, almost elastic quality) fitted together by a group of artisans in Anping, China.

The success of Kukje enabled SO – IL to begin making a name for itself as a formidable force in the design of architectural spaces for art. In 2012, the studio was commissioned to design the first Frieze New York, then over the next few years, Tina Kim Gallery in New York, the Jan Shrem and Marina Manetti Shrem Museum of Art at the University of California in Davis, the K11 Art and Cultural Centre in Hong Kong, the Beeline in Lisbon and, most recently (completed in 2021 and 2022, respectively), spaces for the Amant Foundation in New York and Site Varrier in France.

Although SO – IL’s commitment to civic spaces and housing (both in New York and abroad) remains lesser known, it is as noteworthy as the studio’s work in the art space. For a project entitled ‘Transhistoria’ with the Guggenheim, New York, and their series ‘stillspotting nyc’ in 2012, SO – IL teamed up with local writers and performers in Jackson Heights, Queens – a neighbourhood of 138 languages and home to immigrants from all over the world – to create civic tours based on real-life stories of migration, displacement and community history. Performers told these stories to small audiences in everyday places, such as benches in public squares, hospital waiting rooms, apartments and rooftops. Then in 2016, SO-IL built Las Americas: a development of 60 affordable housing units in the centre of Leon, Mexico, a city known for its sprawling public housing bureaucracy, and having historically built ill-resourced communities far from the centre and its services. With two open courtyards and with no two units facing each other, the complex offered its tenants not only homeownership but also privacy and a sense of dignity.

SO – IL’s newest art space, for kurimanzutto in New York, which opens in November 2022, is something of a marriage between their interest in art and in civic potential. A gallery that began life as a stand in a market in Mexico City in 1999, kurimanzutto has a community-oriented ethos that shares much with that behind SO – IL. The gallery’s new space is deliberately permeable and inclusive, and reminiscent of not only its Mexico City origins but also the many other spaces they had used to present exhibitions by their artists. The building will have a large central exhibition space, with additional areas for refreshments and reading, and a bar for socializing, as well as a viewing room and back offices. ‘We want this to really feel like a space where objects talk to each other, where people feel they can form relationships and friendships, and connect with each other’, Liu tells me.

At the root of kurimanzutto’s design is the inviting, immersive quality SO – IL has become known for across its art, civic and living spaces. But even at this point in their career with their signature aesthetic and ethical principles, both Liu and Idenburg agree they enjoy working most from a place of experimentation, not unlike from where they started. ‘We’ve got an ongoing curiosity and excitement we have for things we don’t know, and how to explore new areas, new ways in which people can engage,’ says Idenburg.

Main Image: SO – IL, Pole Dance, 2010, MoMA PS1, New York. Courtesy: Iwan Baan